Firm of Peter Carl Fabergé (Russian, ca. 1870-1920)

Gatchina Palace Egg

gold, enamel, silver-gilt, portrait diamonds, rock crystal and seed pearls

executed in 1901

Provenance

Acquired by Henry Walters, 1930

Collection of Walters Art Museum

Fabergé And The Russian Crafts Tradition:

An Empire’s Legacy

Gatchina Palace Egg

House of Fabergé (Russian, est. 1842) (Manufacturer)

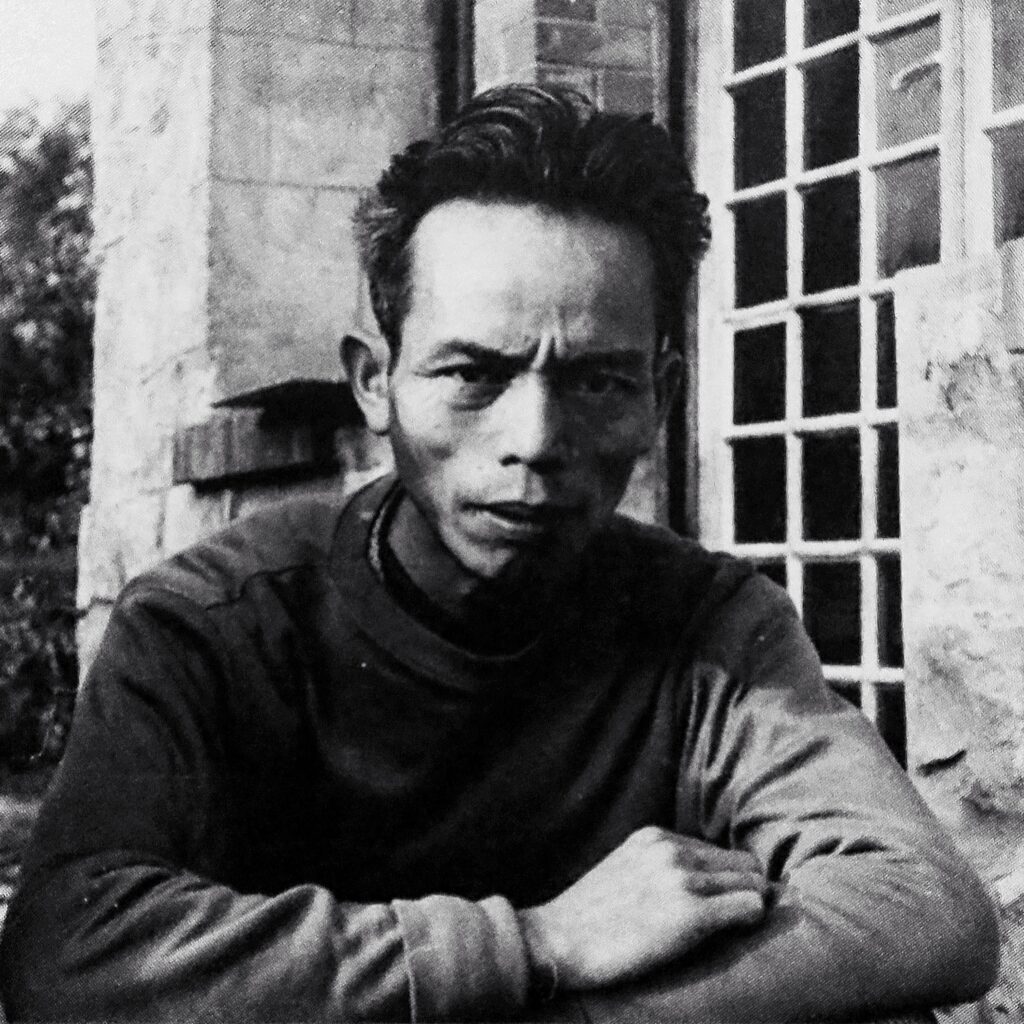

Mikhail Perkhin (Russian, 1860-1903) (Workmaster)

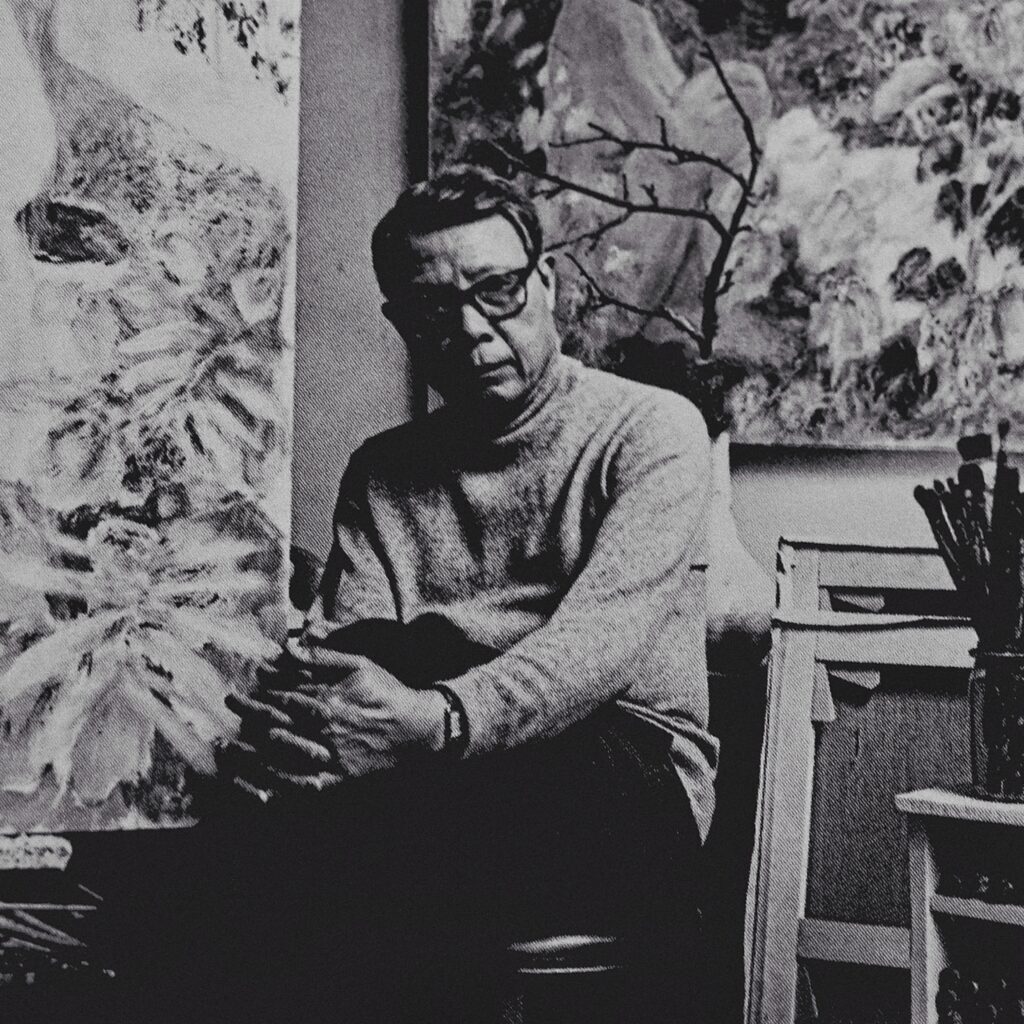

Peter Carl Fabergé (1846-1920) (Jeweler)

As far back as antiquity, decorated eggs have been given to celebrate the blossoming of nature in the springtime. The tradition was taken up by the Church to celebrate the resurrection of Jesus Christ at Easter.

In 1885, to celebrate the 20th anniversary of their engagement, Tsar Alexander III had the idea of giving an Easter egg to his wife Marie Fedorovna. This was the first in a long tradition, perpetuated by his son Nicholas II, who, after Alexander III's death, continued to give them to his mother and his wife.

To make these eggs, the Tsar called on the Fabergé family. This family of Huguenots left France in the 17th century, following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The Fabergés settled in St. Petersburg in 1842, where they quickly established a successful jewelry house.

After this first egg, which the Tsarina loved, Peter Karl Fabergé was given carte blanche to imagine the craziest eggs, in the most precious materials: crystal, gold, silver, precious stones, pearls, enamel... He had only one constraint: the egg had to contain a surprise related to the imperial family.

In all, 54 eggs will be made for the Tsar and his family, and 17 for private clients.

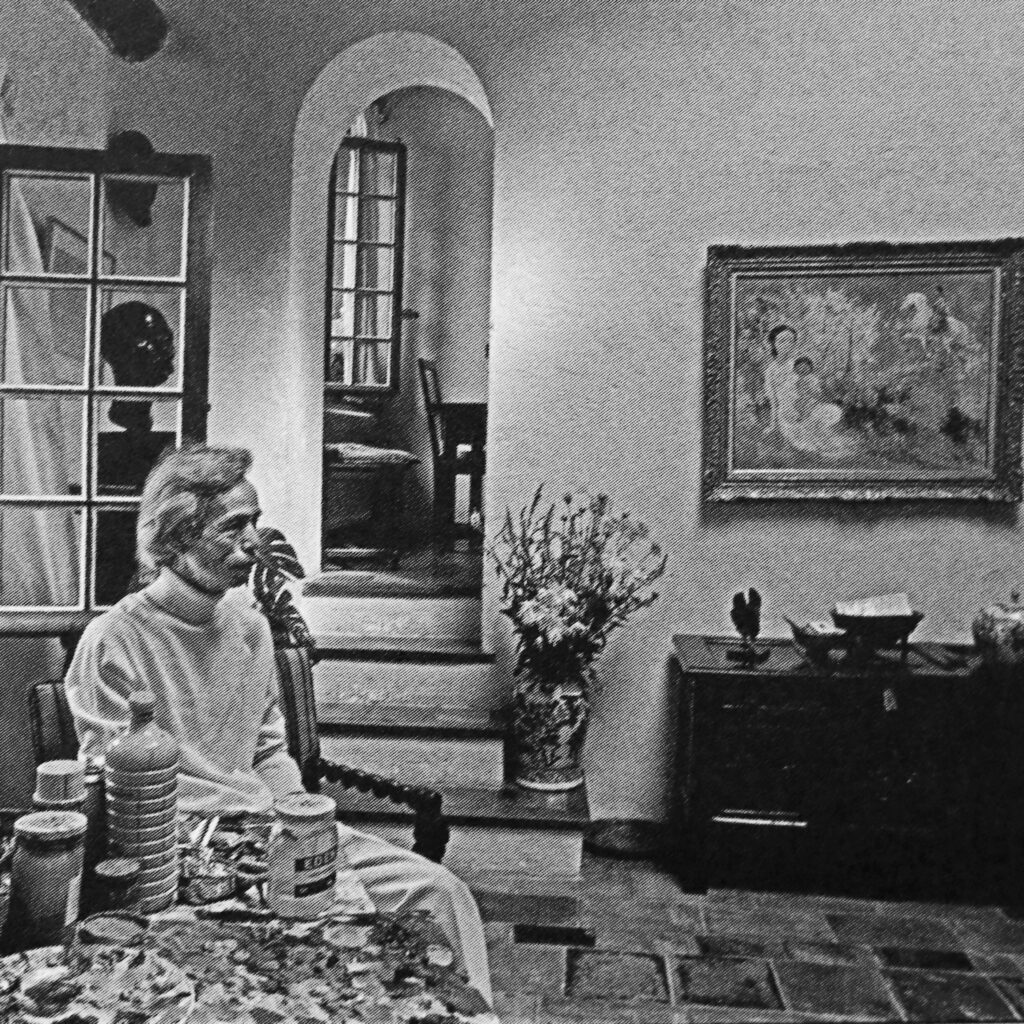

The egg you can taste today was presented by Nicholas II to his mother in 1901. Made by Mikhail Perkhine for Fabergé, it conceals a miniature gold replica of Gatchina Palace, the imperial family's property south of St. Petersburg.

It is currently at the Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, Maryland), which took the photograph.

When the Russian Revolution brought about the fall of the Romanovs, the eggs were looted and scattered around the world.