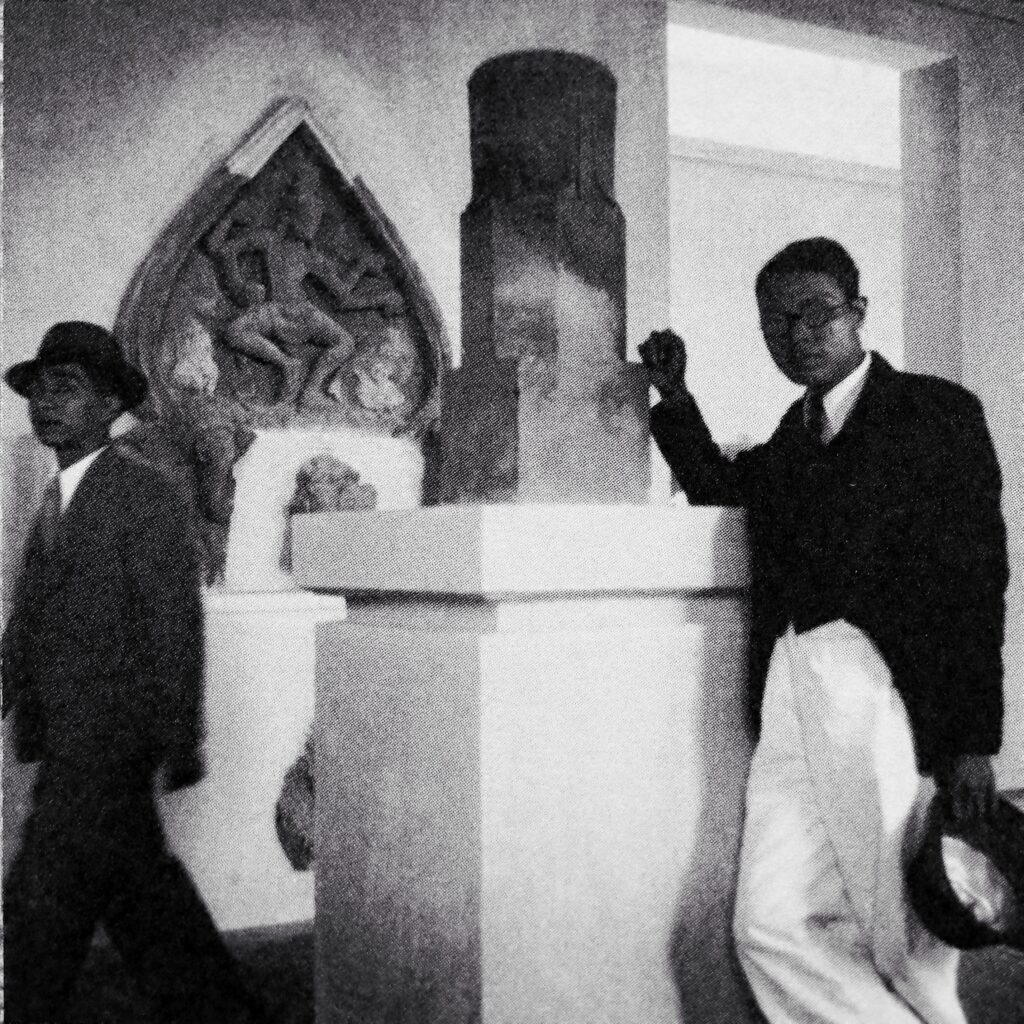

A Stone Figure of Dancing Shiva

Cham art, Tháp Mẫm Style, Bình Ðịnh, Vietnam, 11th – 12th Century

stone

113 cm. (44 1/2 in.) high

Provenance

Collection of a French officer in Vietnam, brought to France in 1952

Acquired from the above in 1986

Private Collection, Europe

Christie’s Hong Kong, 29 May 2016

Price Realised HKD 750,000 at Christie’s Hong Kong, 29 May 2016

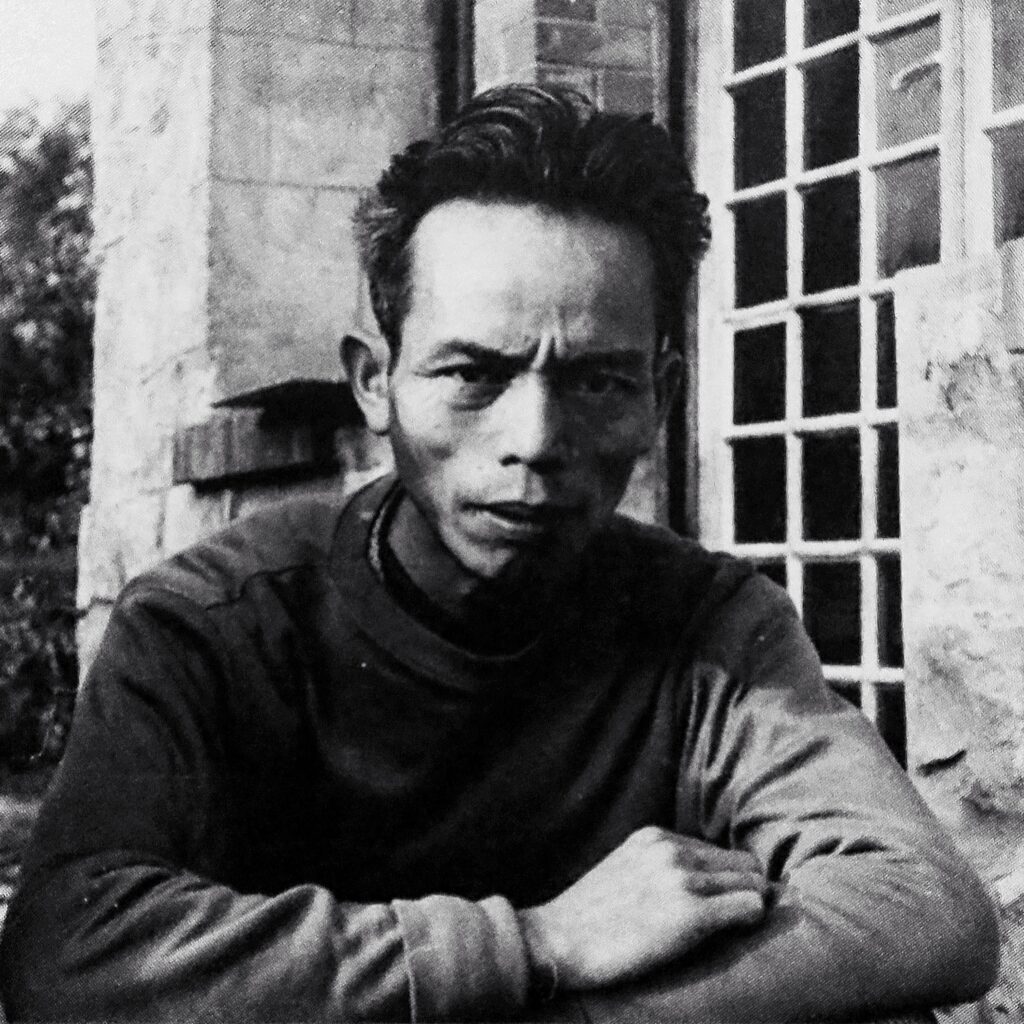

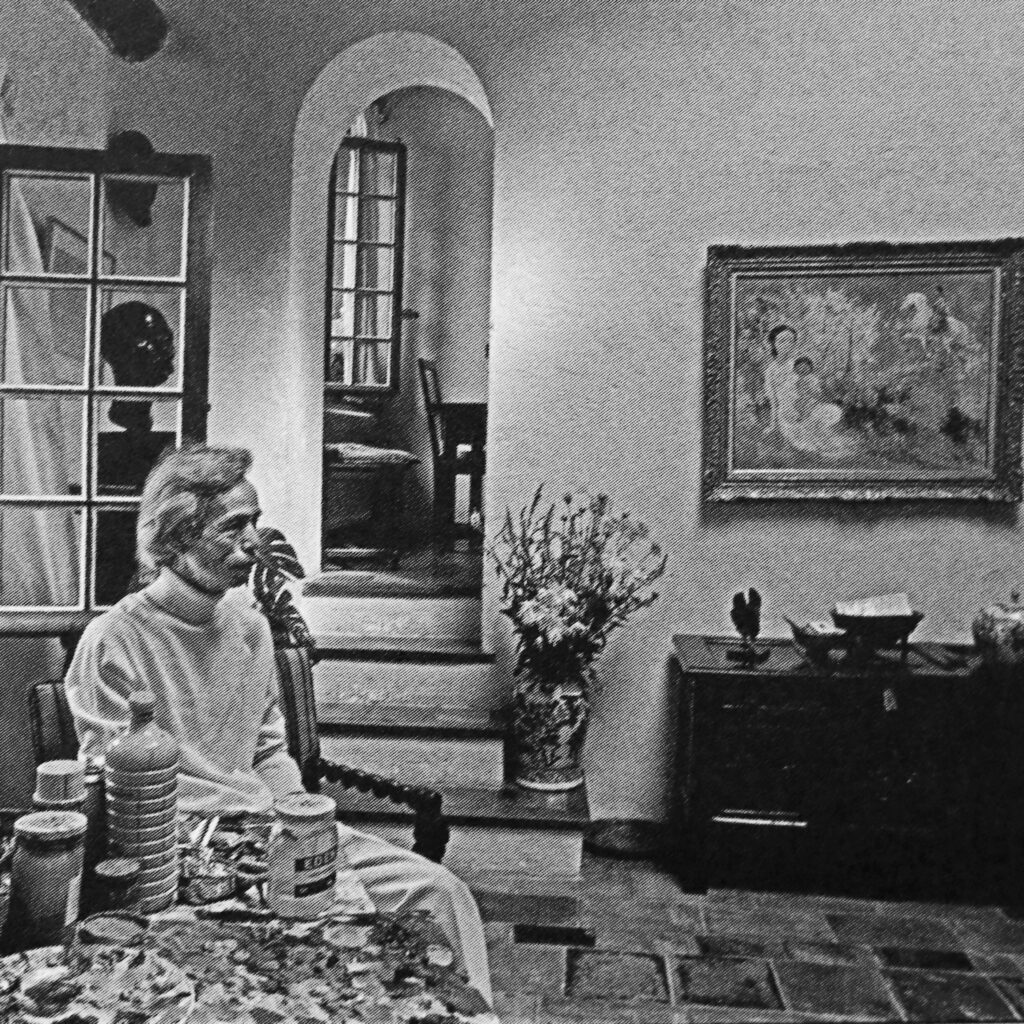

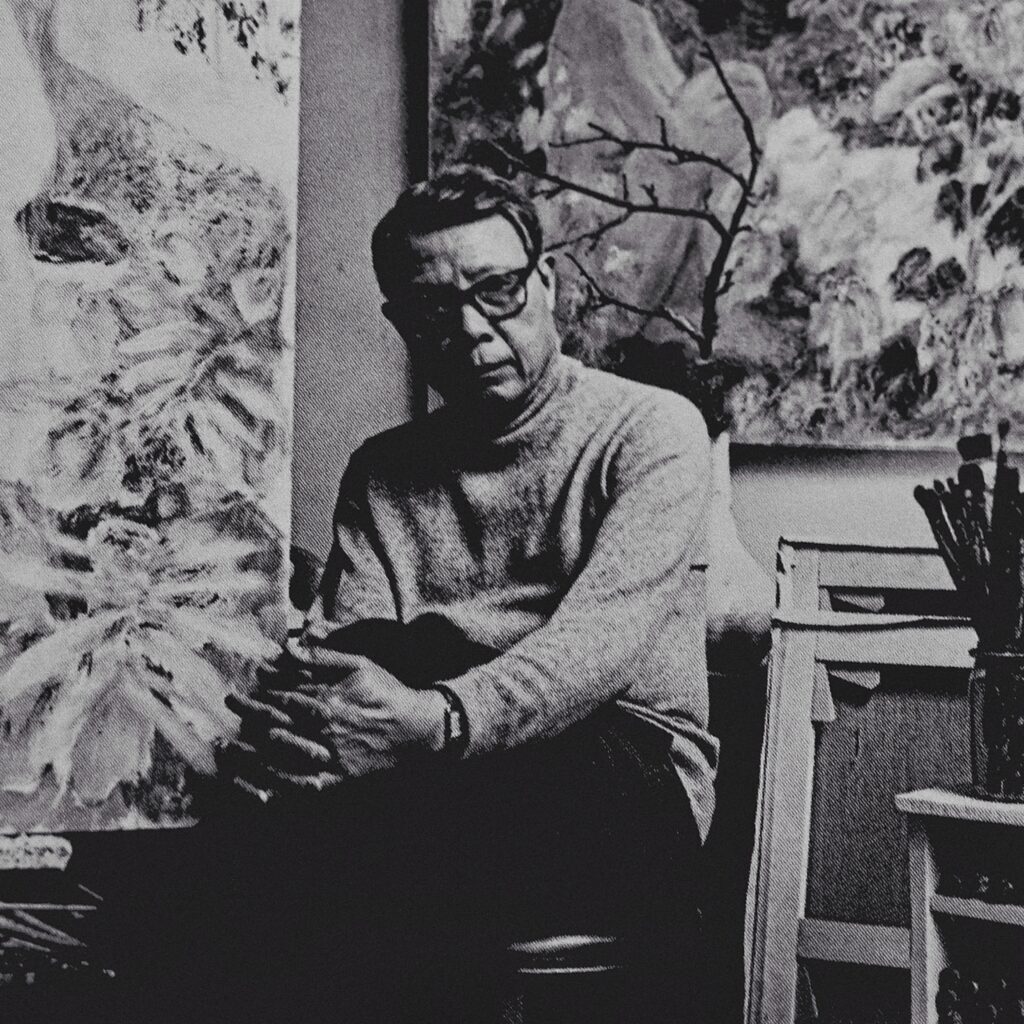

TO BE OR NOT TO BE: VIETNAMESE ART SINCE THE CLASSICAL TIMES

Part of the idea to present this collection of Vietnamese art, Se Souvenir des Belles Choses: A Curated Collection of Vietnamese Art, is due to the fact that Vietnamese art is historically built on interactive layers of cultural interaction and influence that makes it profoundly unique and original. The curated sale brings together three elements of classical arts and antiquities – Dong Son culture, Cham art, and Buddhist sculpture – in contrast to 20th century Vietnamese modern painting. The bigger idea here is to explain the uniqueness of Vietnamese art, particularly its power of assimilation. A strong and confident sovereign-state is able to last and to grow only when its people are able to accept, integrate and take ownership of outside influences.

Modern Vietnam as we know it today was established over an extensive period of time partly through the traditional Nam Tien (march to the south). This descent southwards by an essentially Sinicized population from a historical and mythical location in the Viet culture – the Red River basin in the North – towards the centre and the South’s more Indianized cultures such as Champa (from Quang Binh to Ba Ria - Vung Tau) and the Khmer country (Mekong delta) happened over a period of several centuries. Yet it would be a partial tale of history to reduce this to a one-way movement occurring from the 10th to the 18th centuries. Indeed, the Vietnamese identity was also created by a surge upwards of intellectual Indianized concepts towards the North stretching to as early as the 2nd century BC. It is at an early and fundamental stage that concepts of Buddhism, Hinduism, Sanskrit and rituals from India started being revealed in Vietnamese art, at the same thing that Chinese concepts such as Confucianism, Taoism, and Mahayanist Buddhism did.

It is as early as the 6th century BC that drums and other bronzes such as situlas and weapons of the Dong Son culture was produced and found in the north-east and southeast of present-day Hanoi. It was only later, closer to our era that the village of Dong Son was discovered as the site of origin of most of the first bronzes identified in the 1920s. Situlas were discovered in the north of Vietnam while the drums were discovered in a much larger area. The present situla, decorated with several bands of raised geometrical patterns and two carved handles in the shape of loops is outstanding for its good condition, its larger than average height, its beautiful dark patina, and the geometry of its patterns.

The contribution of Funan (today’s southern Vietnam) in Vietnamese aesthetics comes in the form of skillfully crafted timber and stone sculptures from Theravada Buddhism. Some art historians would make reference back to the 4th century, where artisans created suave and distinct representation of faces and posture. The Vietnamese contribution to Buddhist sculpture from the Theravada school is essential. In the sale, the exceptional lacquered wood standing figure of Luohan from the Le Dynasty of the 18th century is large-sized, showing the unmistakable portrait of a monk instead of a generic visage, making it a rare occurrence in Buddhist art.

Cham art is an absolute pillar of Vietnamese art. In its glorious days, the ensemble of Champa territories used to run from the North of Quang Binh all the way to the edge of the region of Saigon, showcasing the most outstanding sculptures and architectural jewels. Rediscovered by the French scholars, what was once a great civilization managed to survive centuries of vicissitudes, abandonment and wars. In its origin, Cham art demonstrates how an Austronesian population, probably from Borneo during the 4th century, chose to adopt and integrate Indian ideology into its local customs, successfully creating a whole statuary art as imposing as Khmer statuary art. The four examples here show the distinct character of Cham art to take liberties in interpreting Indian traditional religious iconography, creating a true assimilation of foreign influences.