Christie's Invitation to a conference on the special occasion of the release of Gustave Caillebotte, L'impressioniste inconnu by Stéphanie Chardeau-Botteri at Christie's Paris, 9 Avenue Matignon, Paris, 19 September 2023.

Gustave Caillebotte by Stephanie Chardeau-Botteri

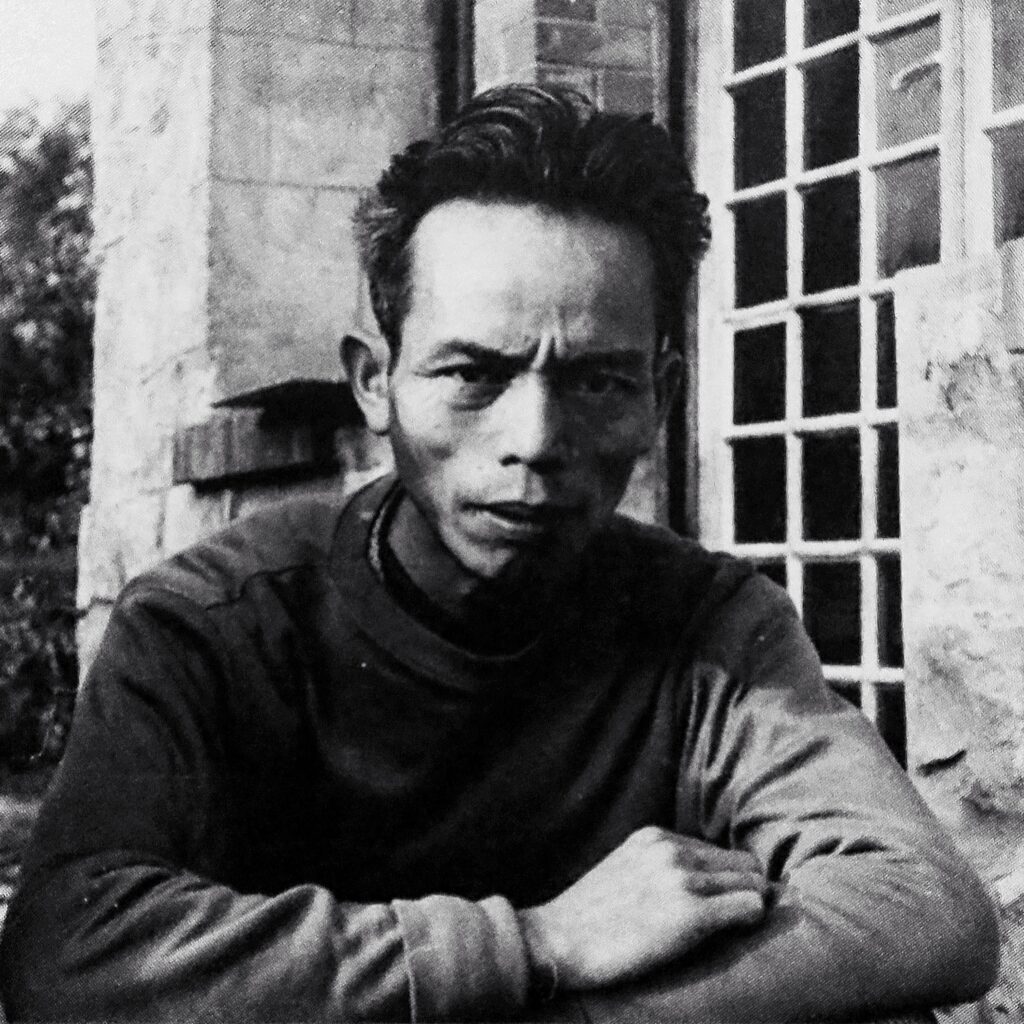

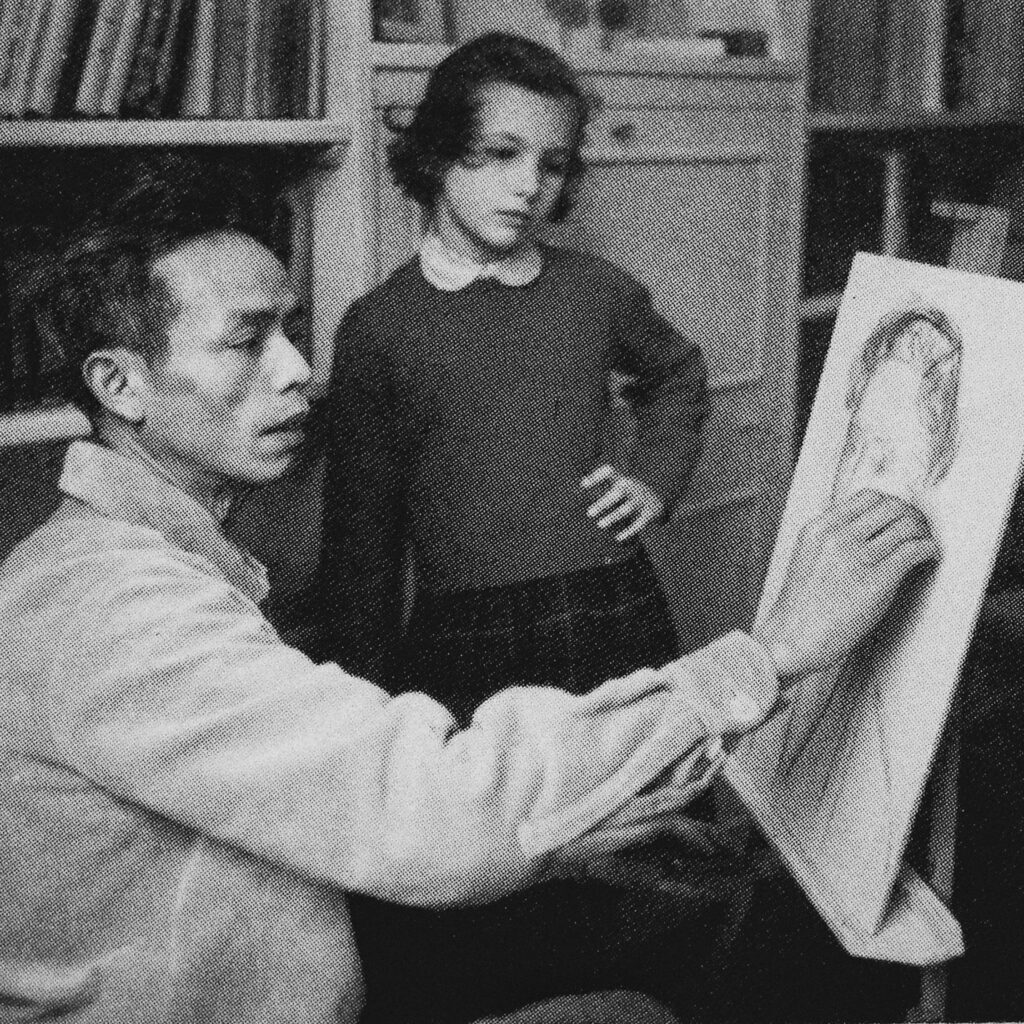

For a long time, our families have known each other. For a long time, I had heard talk of the Josefowitz family, great art enthusiasts, great collectors of Caillebotte. It was my turn to meet them.

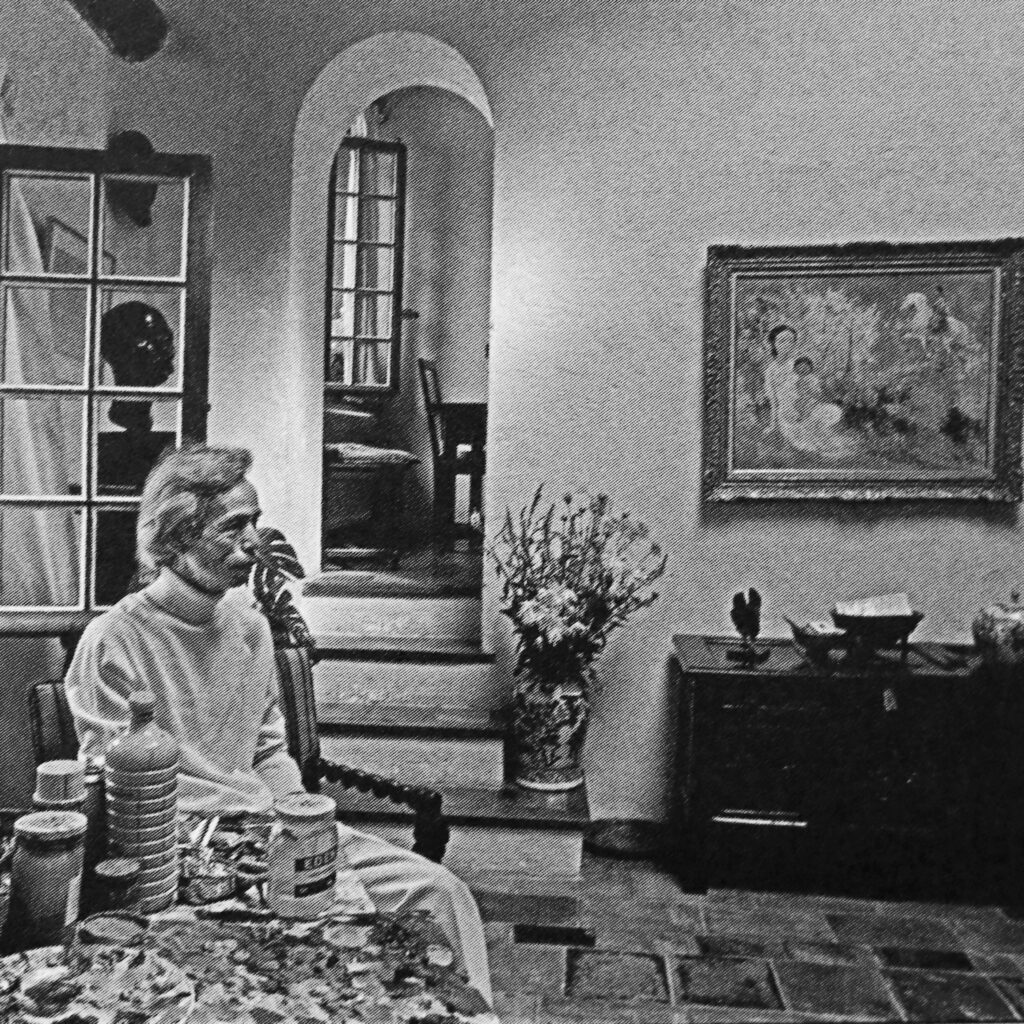

I will cherish forever the memory of this magnificent moment. I remember an elevator, some steps, a brown door, a vestibule. Then the entry to the living room. What an entry. A large sofa, two windows, and between them a majestic Caillebotte which I had never before seen up close.

The Josefowitz family knew how to choose the most beautiful of Caillebotte’s works and they arranged them properly throughout their apartment. There was an oil on canvas representing a greyhound, perfectly highlighted. He bore the name Paul, like that of our host. And the painting had been chosen for this reason. The family left nothing to chance. Indeed, Sam had selected this work because his son’s name had been inscribed in beautiful capital letters at the top right. The artist, who loved dogs and owned many, frequently painted them, like the dog who guides the viewer’s eye in Le Pont de l’Europe, or Dick who comes before Richard Gallo, or the portrait of the female dog of Caillebotte’s companion, Charlotte, depicted three times in three different works. Paul, this elegant greyhound, delicately sat atop a thick, colourful carpet, belonged to the artist’s brother, Martial, a musician and photographer. Both paid homage to their respective dogs, their faithful companions. Gustave with this magnificent painting, Martial through his celebrated photograph of his brother in the company of his dog Bergère walking near the Louvre.

A number of other paintings shared the walls of this divine apartment; their own little museum. But, I will remain focused on the Caillebottes as there were so many more. The Josefowitz family belonged to the rare group of collectors who had discerned, well before anyone else, the genius of this painter, then unknown to others. Their collection contained several masterpieces such as L’Homme au bain, Le Pont d’Argenteuil sur la Seine, Nature morte aux huitres, and Bassin d’Argenteuil. They had fallen for many portraits: that of the celebrated bookseller Émile-Jean Fontaine, of Jules Dubois, Pierre Rabot, and a standing soldier. Caillebotte was known to represent his models in their element, their place in life. This is true with Portrait d’Eugène Daufresne lisant.

Eugène was the cousin of the artist’s mother, née Céleste Daufresne, from a great family in Lisieux. At twenty-eight, she married Martial Caillebotte in 1847 and gave him three sons: Gustave, René, and Martial. Very close with her large family, Céleste loved to receive them at her Parisian house, a mansion constructed ten years before, number 77, between the rue de Liège and the rue de Miromesnil. Thus, Gustave took advantage of one of Eugène’s visits to immortalise him, and now we can admire him too. In attire befitting the era’s bourgeoisie, Eugène occupies the exact place of the artist’s mother in an earlier portrait. In these two regal works, we can identify the same red velvet chair, which matches the curtains, the same white marble fireplace, the same golden clock. And both figures hold the same pose. They are concentrating on their work and nothing can distract them – not even the artist at his canvas. There, the mother of the artist embroiders designs destined for her sons; here, Eugène reads. Reading was an important pastime to the Caillebottes and they devoured all books, classic or contemporary. And what does Eugène read? We cannot know, but it seems, in light of its soft cover, to be most certainly a modern work, something by Zola or Flaubert perhaps. Gustave, fond of these books, could very well have lent his uncle one, both to share his passion and for the sake of the painting.

And Gustave had many other passions.

Besides painting, collecting, and philately, he was a keen sailor. He became a member the Cercle de la voile de Paris in 1876, won almost all the regattas in which he raced, and owned fourteen sailboats; he designed twenty-two. He made his debut on the banks of Argenteuil but quickly came to practice in Normandy. With his brother Martial, he did everything he could to win, changing the ballast, preferring lengthy keels, silk sails… The Channel had no secrets from him! Never abandoning his brushes, instead he benefited from time in Normandy and painted its countryside and the beautiful villas that overlooked the sea. Trouville was his favourite seaside resort, and it was the subject of twenty-some paintings. The pink villas with their red bricks inspired him, and there was such an embarrassment of riches, permitting Gustave to tackle one of his favourite subjects, plunging views that lead to clustered rooftops. Following his famous Toits de Paris, he attacked the roofs of Normandy which were just as unusual. Trouville, la plage et les villas is one of these beautiful paintings of the town that unite elements distinct to the artist: pronounced low angles, flat areas of paint, the use of a variety of grey tones specific to his Parisian worlds to which he added touches of colour. Note the angle that the artist chose to encompass the small carved turret and illuminated solarium – it adds a certain je ne sais quoi to this work.

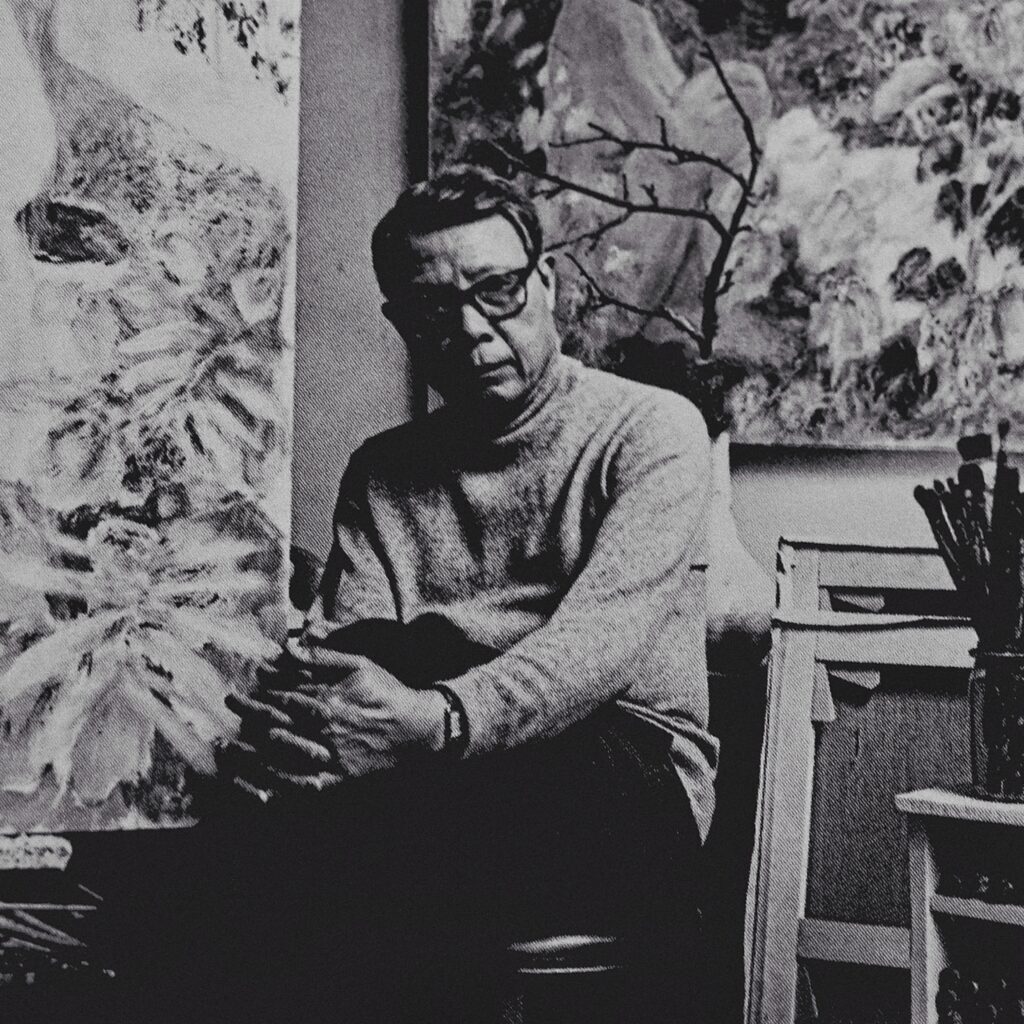

In order to sail as often as he wished, Gustave bought a house in Petit-Gennevilliers in 1881, and at this pretty, two-storied home, he was able to paint as well as sail. Accordingly, he completed several works depicting Petit-Gennevilliers and its long coloured plains. Caillebotte had left behind his greys for, like his friends Renoir and Monet, more cheerful colours – colours that shimmer. On the advice of Renoir, he used more violet, green, and yellow.

The dimensions of Verger aux pommiers en fleurs, Colombes more closely conform to the canvas sizes of this period. With its light colours, small, rapid brushwork, and representation of the effects of light and shadow, this painting is indeed an impressionist work. There is a feeling of real wind blowing through the branches of these apple trees. The delicate flowers presage the forbidden fruit which has seduced so many artists who shared ideas at the Café Guerbois and then later, the Nouvelle Athènes. Monet, Sisley, Pissaro all painted these famous flowering apple trees that announce the coming spring. And the craze for plants did not only affect the painters.

‘Advances in the sciences and transport encouraged a massive influx of plants from all over the world. In ten years, more than two million exotic and unknown plants had been introduced in Europe. They then had to acclimatise to their new surroundings and were thus transformed. The number of gardeners who practiced the art of crossbreeding grew’ (S. Chardeau-Botteri, Gustave Caillebotte, L’impressionniste inconnu, Paris, 2023, p. 260). And Caillebotte was caught up in turn.

Having sold his famous collection of stamps in 1887, he need a new activity, and beginning in 1888, Caillebotte turned towards gardening. And, as with everything he did, he gave two hundred percent. ‘He decided to lay out the garden himself, perfectly trimmed, installing geometric beds of dahlias, hyacinths, irises, poppies, sunflowers, daisies, and gladioli. All day, clogs on his feet, he planted, made cuttings, watered. He was very proud of what he cultivated and spared no expense for its improvement’ (ibid., p. 262). Gustave shared this passion with Monet who was already living at Giverny. The two corresponded at length, sharing advice and exchanging cuttings and baskets of flowers. For all their enthusiasm, however, they never forgot their principal passion. As soon as he could, Caillebotte seized his famous brushes in order to paint his new creations. The 1890s saw an abundance of canvases depicting daisies, roses, irises, gladioli, and dahlias. But also the immense Capucines. Caillebotte gave himself the project of redecorating his dining room; this explains the painting’s considerable dimensions. Almost aquatic, the work, in effect, foretells what Monet would paint ten years later with his famous water lilies. It also foretells the arabesques and plant themes that will define the future Art Nouveau.

At the end of his short life, during the winter of 1892-1893, Caillebotte painted several canvases of chrysanthemums, a premonition of sorts. These he offered to his two great friends. Renoir received a magnificent bouquet in pastel tones, placed in a white Japanese-style vase with blue tracery. Monet was to receive an enormous bouquet of chrysanthemums, the subject treated in an unprecedent manner without a background or a vase. But Gustave never had the time to give the painting to his friend; it would be Martial who presented it. Monet never wanted to part with the painting and he kept it until the end of his life.

Gustave Caillebotte passed away in February 1894. His legacy caused a stir. Fortunately, some discerning collectors believed in his work. They collected it, presented it at various exhibitions, and lent it to museums. This was the case of the Josefowitz family, whom I would like to thank.