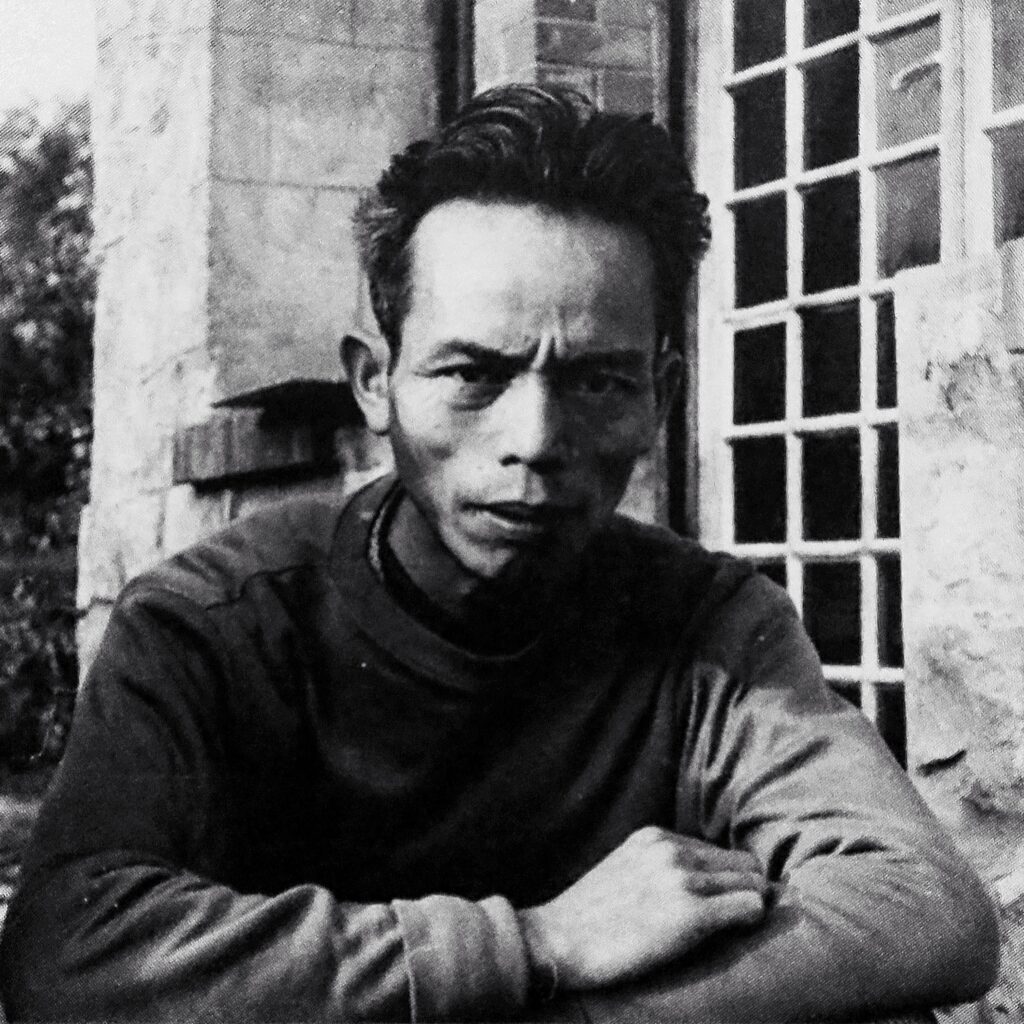

Le Pho (France/Vietnam, 1907-2001)

Landscape of Tonkin (Paysage du Tonkin)

signed, signed again in Chinese lower right

lacquer on panel

201 x 80 cm. (79.1 x 31.5 in.)

painted ca. 1932-1934

“Paysage du Tonkin” (Landscape of Tonkin) is a lacquer on the panel of exceptional dimensions — the largest known lacquer executed by Vietnamese master Le Pho.

LE PHO "PAYSAGE DU TONKIN", 1932-1934, OR THE CHOICE OF THE DREAM AGAINST THE MEMORY

“Paysage du Tonkin” (Landscape of Tonkin), signed, signed again in Chinese lower right is a lacquer on panel of exceptional dimensions (201 by 80cm for each of the three panels; total201 by 240cm), the largest known lacquer executed by the painter.

This superb example of Vietnamese lacquer painting, created between 1932 and 1934, was presented as a wedding gift in Hanoi in 1935 to François Lorenzi, son and adopted son of Orsolla and Auguste Tholance. Prized for its excellence, rarity, condition, and historical and sentimental value, the present work was meticulously kept in a French family for years.

It was a wonderfully emotional and aesthetic shock to discover it, in the early 2000s, in the family’s beautiful light-filled apartment in Boulogne, a residential area close to Paris.

Being allergic to the resin that is used to make lacquers, then Le Pho settling in France, where the necessary humidity conditions for the execution of the lacquer proved to be difficult, soon abandoned this technique from his repertoire.

Works on lacquer by Le Pho are extremely rare, and only a few have surfaced from private collections: A lacquer box, made in 1930 as a gift to Victor Tardieu, director of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine, Hanoi, exhibited in “La fleur du pêcher et l’oiseau d’azur“, Musée royal de Mariemont, Belgium, (catalogue p 162 n* 9.06) ; A folding screen entitled “Paysage Tonkinois, Sai-Son, Province de Son-Tay” (Tonkinese Landscape, Sai-Son, Son-Tay Province), which was exhibited at the 1931 Colonial Exhibition in Paris and reproduced in the book Trois Ecoles d’Art de l’Indochine (Three Schools of Indochinese Art) published in Hanoi in 1931. Another lacquer screen, also formerly in the Tholance-Lorenzi Collection, executed circa 1935, entitled “Eternités” (Eternities). And one other very similar. We can also mention “a small screen in gold lacquer “Wild Geese and Egrets” cited by Victor Tardieu in his report on the participation of the École des Beaux-Arts at the Colonial Exhibition in Paris in 1931.

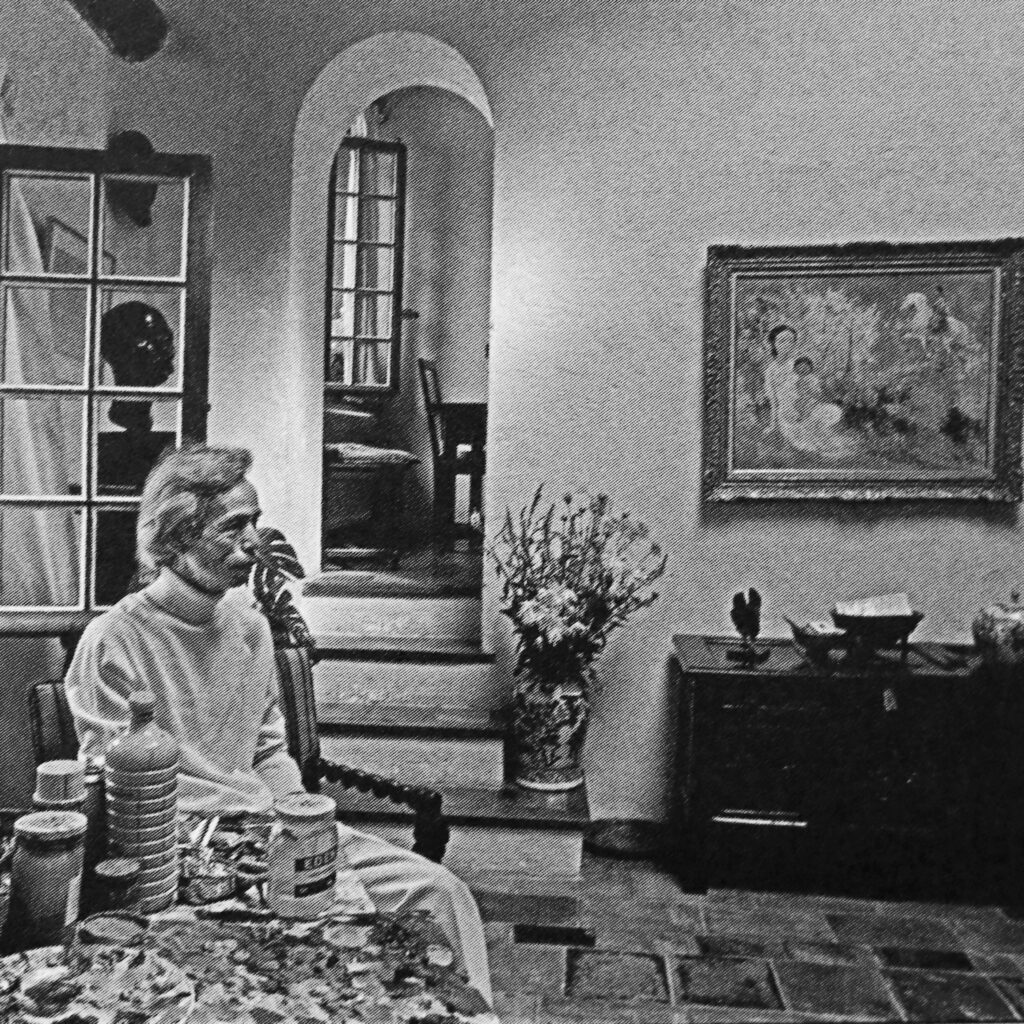

First, let’s talk about these characters, this man and this woman, who together created a magnificent collection with taste and pre-science.

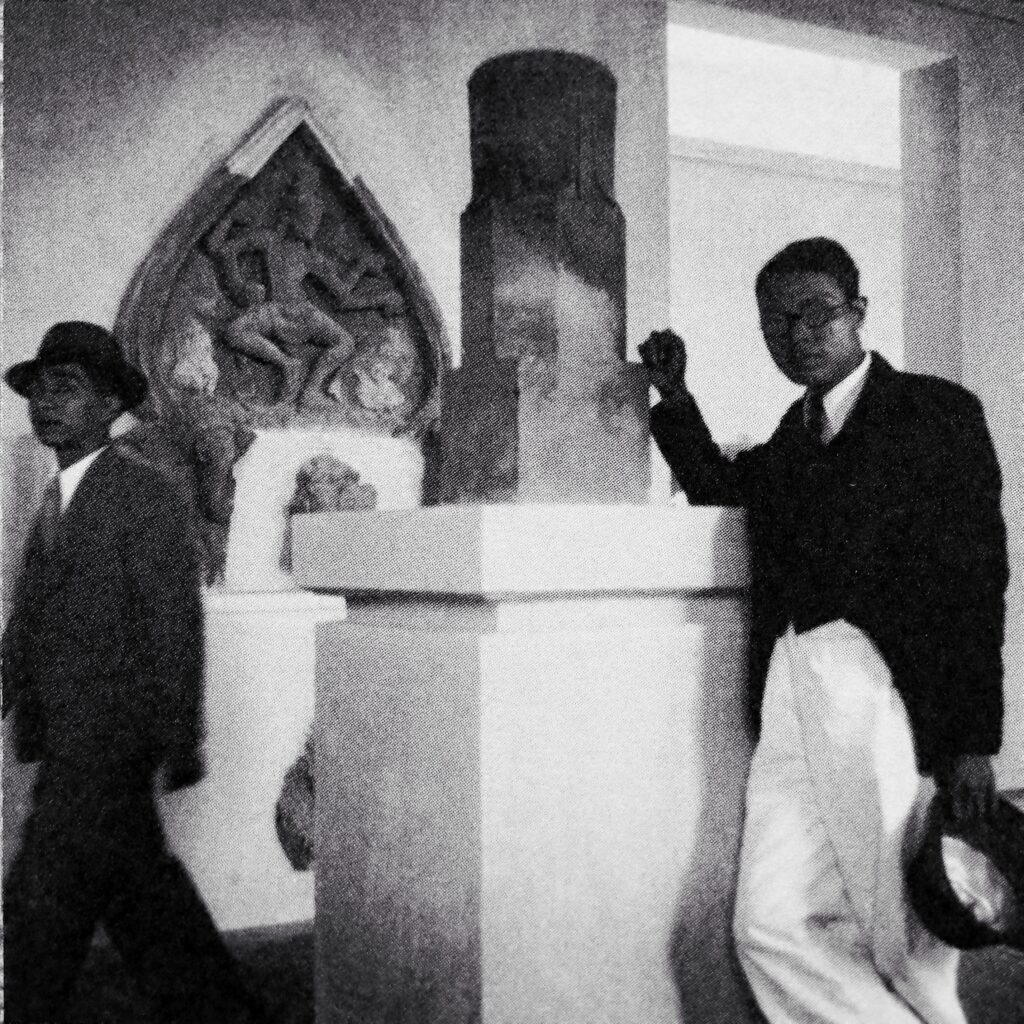

Orsolla Guglielmi (1888-1968) was born in Piazzali, a small village in Corsica, and she married Paul Lorenzi in 1908, who at that time got sent to Vietnam in 1905 as a customs officer. Their son was born in Hanoi in 1909 before Paul Lorenzi was killed during the 1914-1918’s war. In the early twenties, the widow Mrs Lorenzi met Auguste Tholance (1878-1938), who arrived in Vietnam in 1900 and was on the way to a promising career as a French public servant. Both widows (he had two children) married and were determined to leave behind the pains to build together a brighter future. They both had a passion for art and a deep understanding of Vietnamese culture. In the twenties in Vietnam, a study of art was in full effervescence: Henri Parmentier had already published his “Inventaire des monuments chams de l’Annam” (Inventory of Cham’s Monuments in Annam), Jean-Yves Claeys was digging Tra-Kieu, Louis Pajot discovered Dong Son, the so-called “Tan Hoa ceramics” was described by Pouyanne. So many initiatives. All these discoveries generate enthusiasm and stimulation, questioned the couple Tholance-Lorenzi. They started collecting ceramics from the Ly and Tran periods and were fascinated by the Cham and Khmer temples et statues

Orsolla Tholance encouraged governor general Merlin to sign the order dated 27 October 1924 to create in Hanoi a “Fine Art School of Indochina“ under the aegis of Victor Tardieu. As time tells, this institution will become the centre for many great artists during the XXth century.

As time goes, Auguste Tholance proved to be an outstanding public servant. In 1930, he became the Cochinchina governor and was a Résident supérieur of Tonkin from 1931 to 1937. During all these years, Orsolla and Auguste Tholance learned and developed a deep understanding as they met artists, followed their exhibitions, and promoted their work to reach their goal: the acquisition of significant art pieces, including, for example, also by Le Pho an extraordinary oil on canvas “Paysage du Tonkin” (Tonkinese landscape),1937 or “Vendeuse de Bétel” (The betel’s seller), 1931.

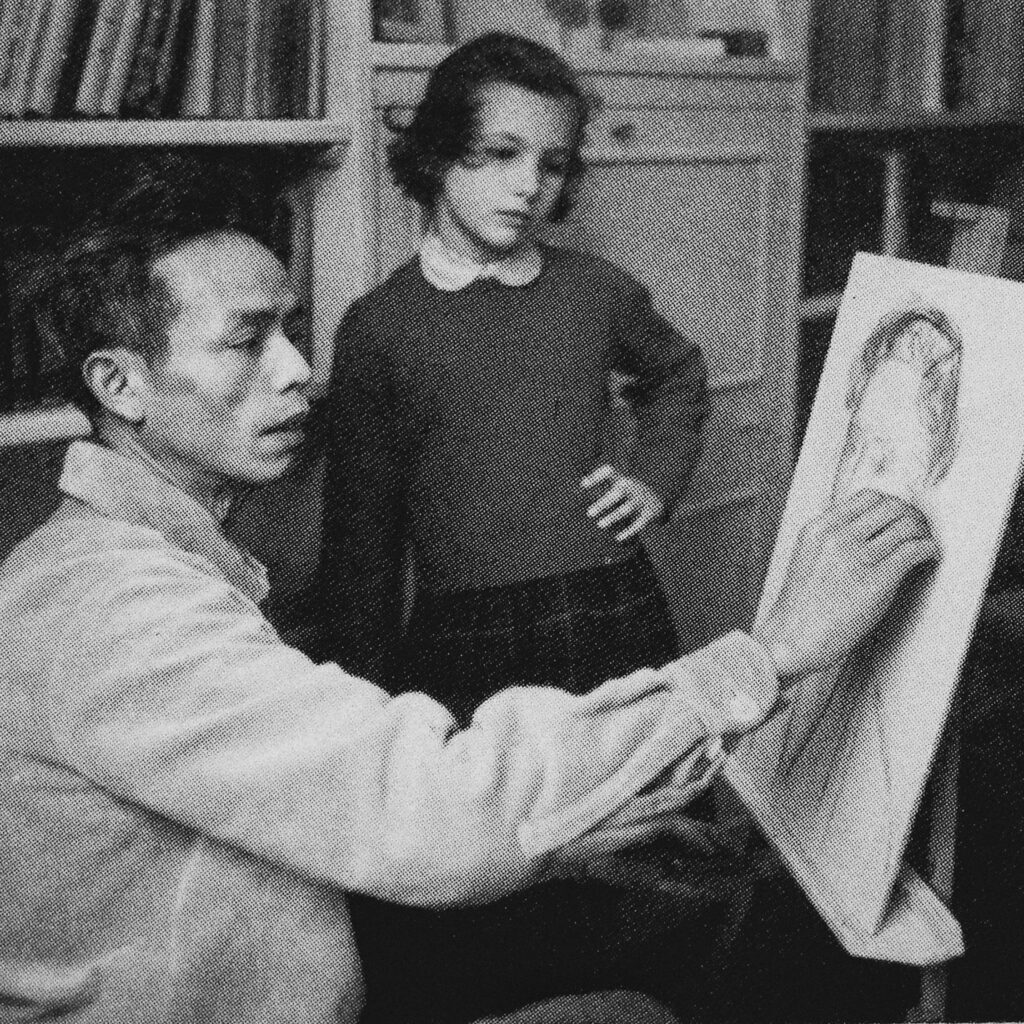

Mrs Tholance was the civil godmother of Le Pho and Le Pho will become the godfather of their grand-grandson.

Secondly, what does the work tell us?

It is made up of 3 panels. What is striking is an apparent asymmetry: the two panels on the right are complementary – the links in colour and gloss mattress well assumed – while the left panel fits less well into the whole. Certainly, the patterns are also aligned, but on the one hand, the tones vary, lighter on the left and on the other hand, the junctions are less clear as at the level of the leaves of the banana tree in the centre and the cactus downstairs.

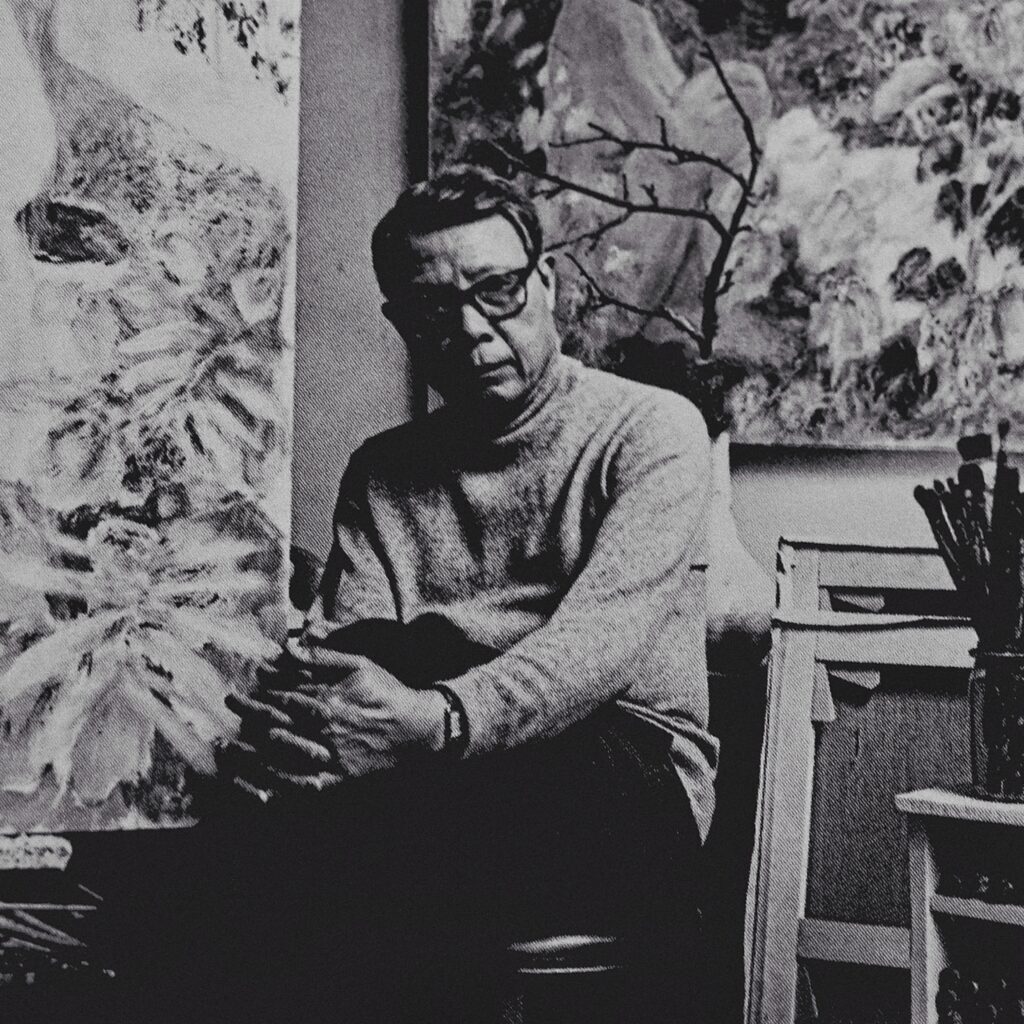

Le Pho incorporated geometric elements that he had borrowed in spirit from Jean Dunand (1877-1942), whom he met at the Colonial Exhibition in Paris (1931). The latter was initiated in the art of lacquer work in 1912 by the Japanese master Seizo Sugawara. We have already mentioned all this.

Assimilating the spirit of oil on canvas painting with that of Vietnamese lacquer, particularly with regard to figurative and spatial composition, Le Pho created an extraordinarily fine painting. A dreamy and phantasmagorical (let’s identify the vegetation…) topography fills this dark-toned Tonkinese scenery. The distant “Moyenne Région” (middle lands) is imbued with a sense of transience and mystery, caused by layers of golden foliage that appears to shift from left to right with each shimmer of light, giving us a perception of reality with a mixture of fascination and apprehension. In the foreground, the foliage acts as a barrier, and the partly hidden landscape is only contemplated and not actually entered.

The figured cactus, an essential element of the lacquer, has nothing to do there: it is a cactus that grows on arid soil and not at all in the exacerbated humidity of the Middle Region. This one can still be identified by the black masses of the mountains and the stylized river, with its abundant stylized vegetation, except for the more realistic banana tree. But it is a deconstructed world, one of those with big questions that know how to offer strong answers. The West of Dunand, inspired by Asia, meets the Far West of Le Pho, inspired by Europe.

A one-to-one acculturation one that makes history stronger than geography. Yet even with all its Western connotations, “Paysage du Tonkin” hints at its Vietnamese essence with its depiction of the souls of Vietnamese identity: the river, mountains and a house’s roof.

For Le Pho, the connotation is not the concession; he has already started his Orphic mission.

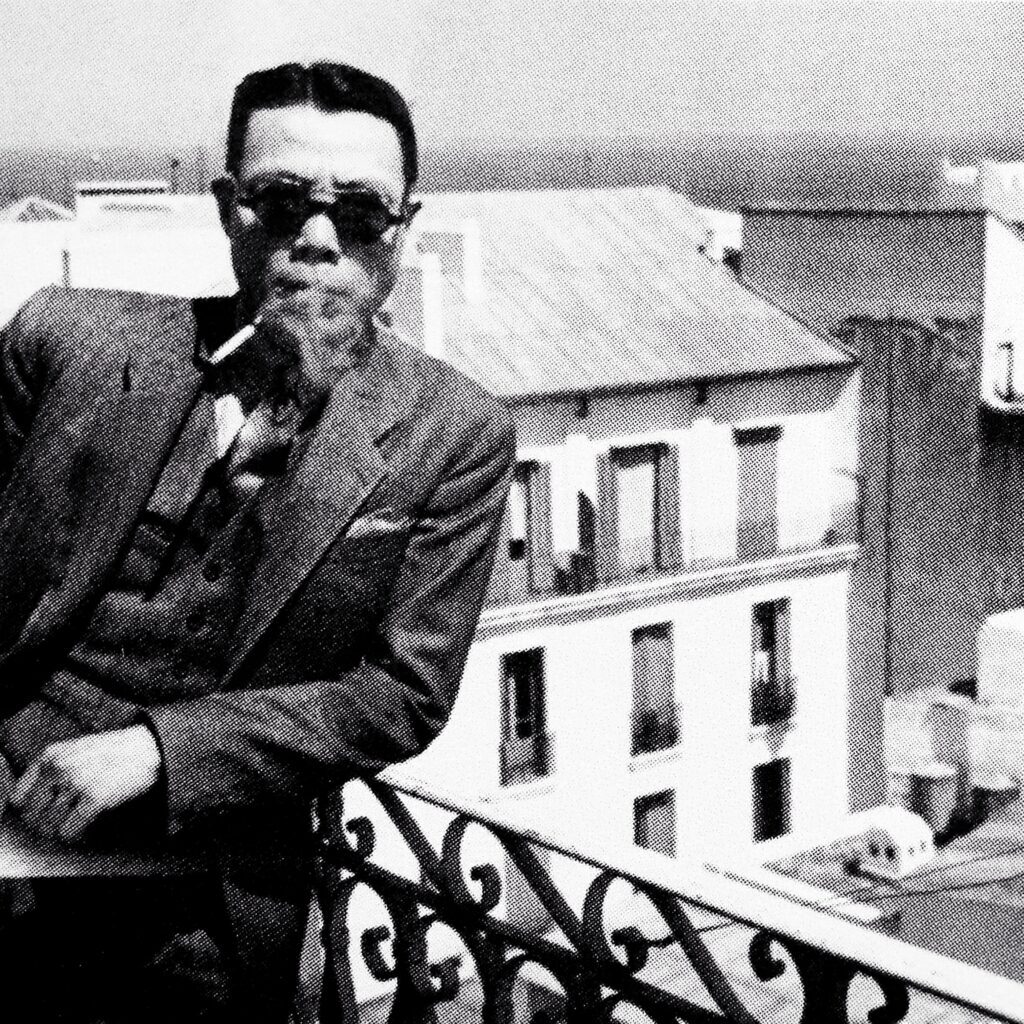

In this year 1934, his decision is made: his choice will be the dream against the memory. Three years later, he settled permanently in France where he died without ever returning to Vietnam.

Jean-François Hubert