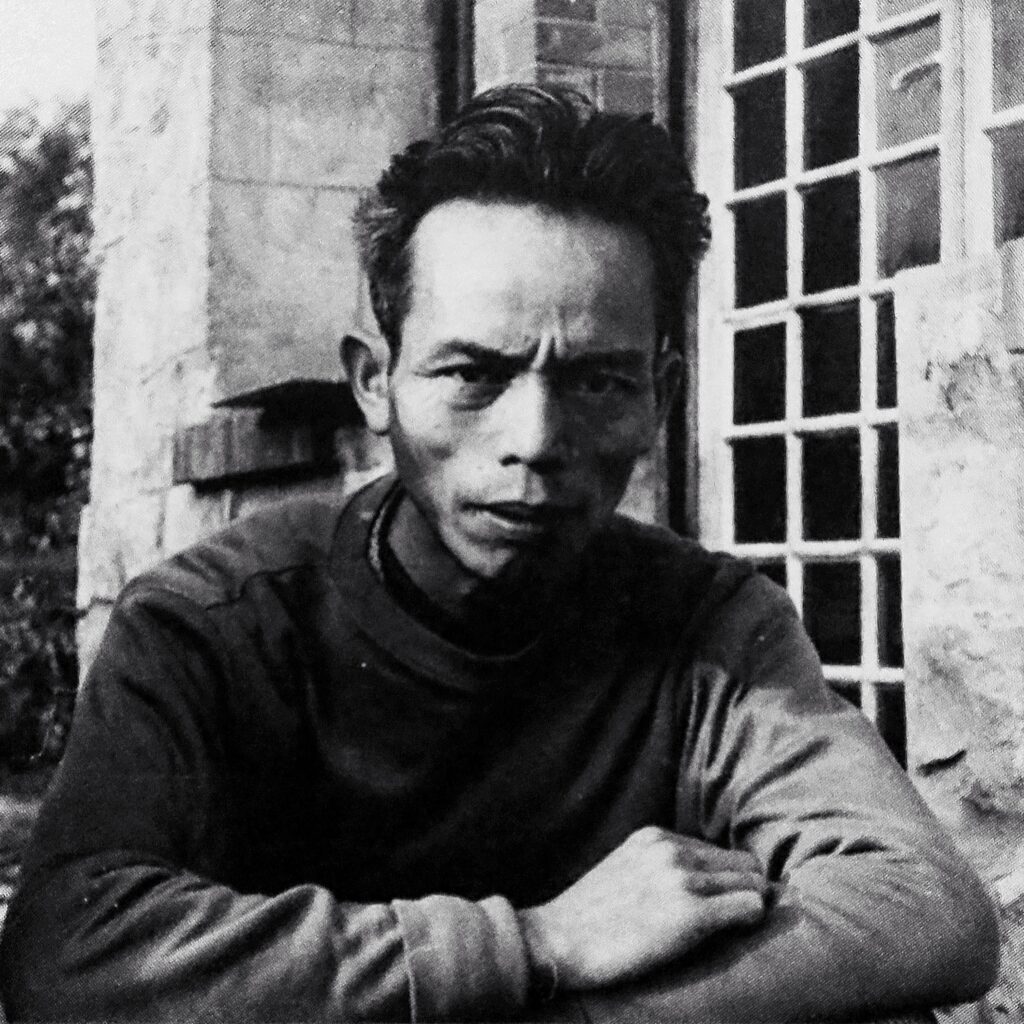

Le Pho (Vietnam, 1907-2001)

La Pagode

signed and dated 'Le Pho 1930' (lower right); titled and dated 'La Pagode 1930' (on the reverse)

oil on paper laid on board

111.5 x 140 cm. (43 7/8 x 55 1/8 in.)

Painted in 1930

In olden times, Vietnam is confronted by a double necessity: to defend the territory and to consolidate the monarchy. For that reason, the ruling powers understood the need to acquire competent administrators who know the law and the application of it.

It is in the perspective of forming a ruling class that the court built, in 1070 in Hanoi, a monument dedicated to Confucius. Originally, this monument used to house three statues of Confucius’ disciples and painted portraits of 72 of his pupils.

In 1075, the first competition for selection was only accessible to the children of the imperial family or of the aristocracy. Little by little the tests to graduate as a “grand scholar” were specified: a solid literary talent, a great capacity to write and a solid general culture based on Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism were to be demonstrated.

Le Pho contemplates the Temple of Literature which remains the same except for the high wall added in 1833. No doubt the painter was sensitive to the beauty of the gardens and the basins, in this magical place where all is serene, and where decoration and architecture appear minimal.

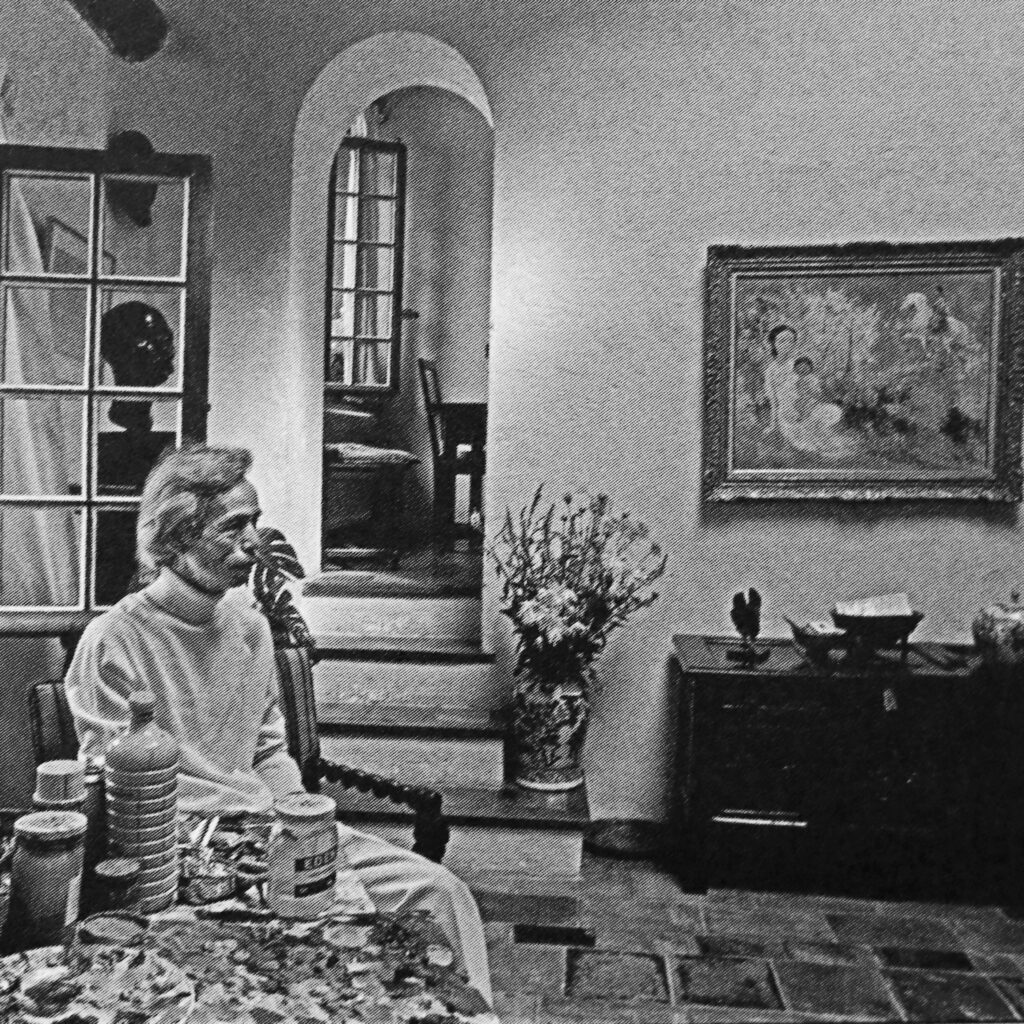

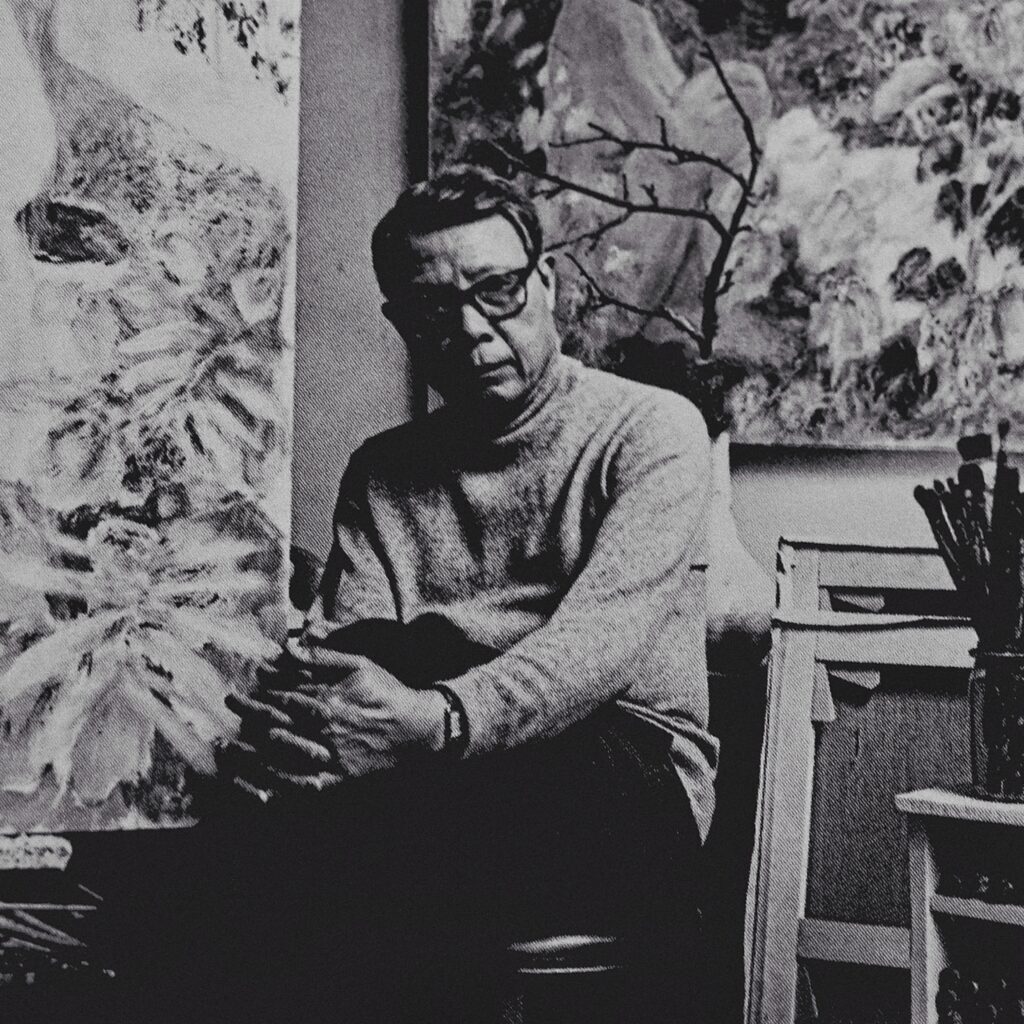

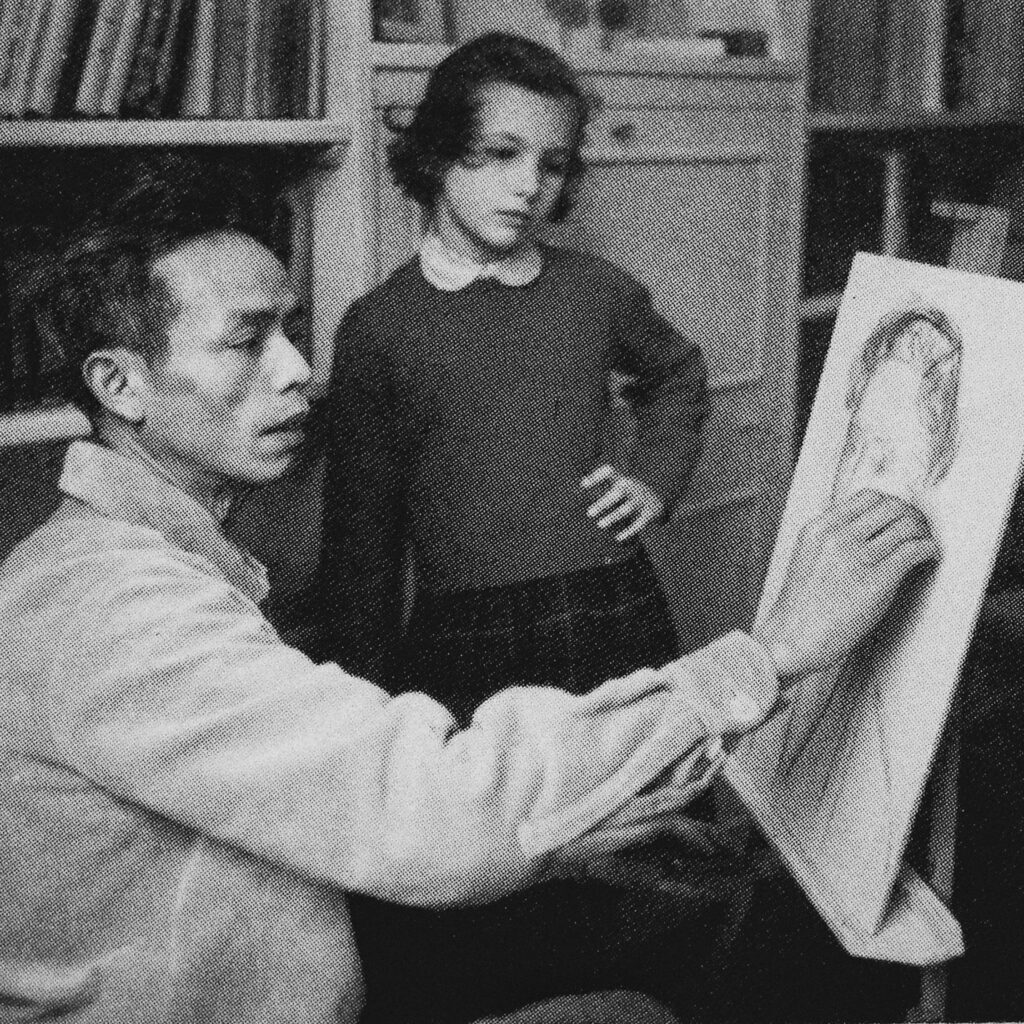

In 1930, it was Le Pho, the young graduate from the Fine Arts School of Hanoi, and the favourite pupil of Victor Tardieu (1870-1937), the director of the school, who painted this imposing large painting, La Pagode.

What does he express exactly, him, the educated Mandarin, whose father used to be the Vice-King of Tonkin? What does he see, a needed homage to a power well gone or a call for help of a power to return?

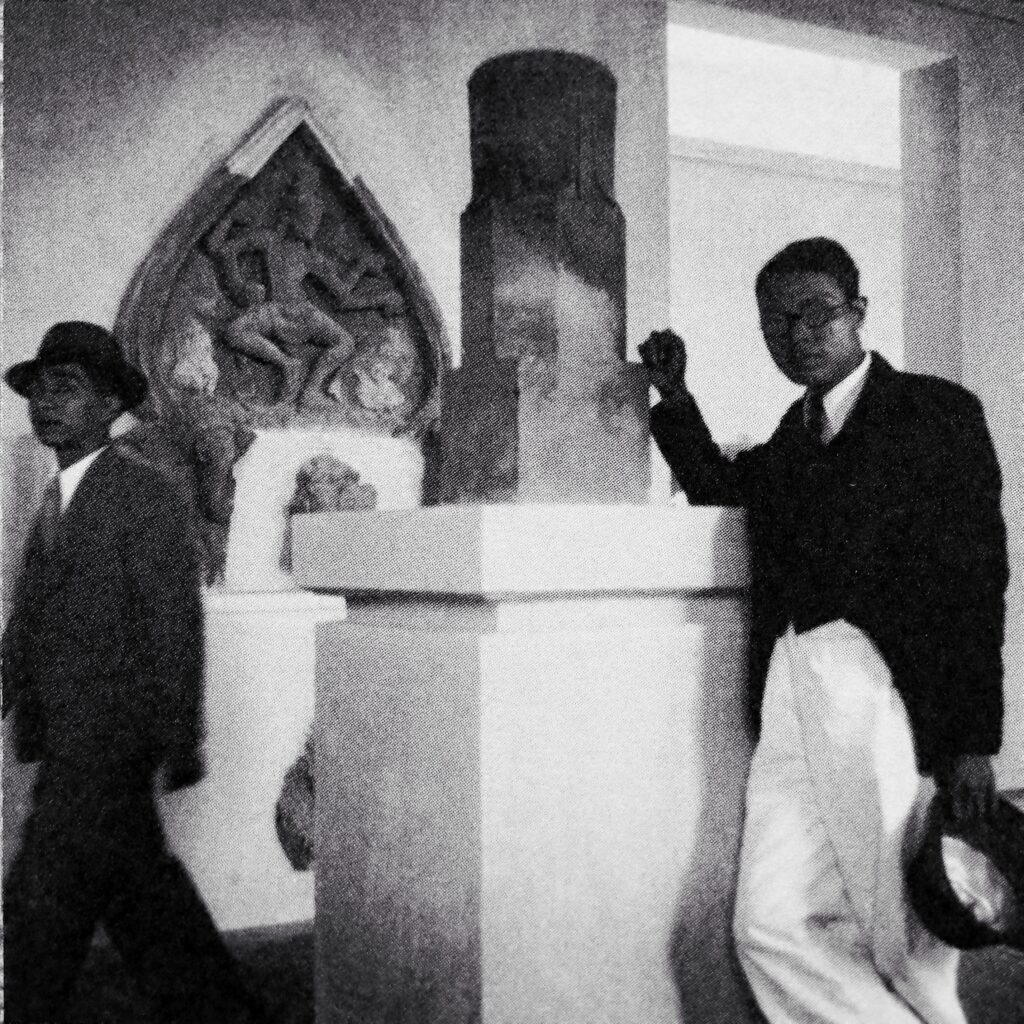

In 1930, Le Pho was already aware for a year that he would participate in 1931 at the Colonial International Exhibition of Paris and dream of his future as a painter. It is by leaning towards universalism that an artist becomes major. It is by putting at risk his own identity that a painter such as Le Pho can reach the absolute.

Let us examine this painting more precisely.

The painter provides us with a vision more charming than solemn of this place. A place he feels deeply towards, but does not celebrate. The buildings are partially described but it is the trees that are the true actors of the artwork: the powerful trunks and its branches frame the buildings. A few characters including a lady and a child are visiting but are no longer the actors of power. The whole scenery immersed in shades of brown and green shows that nature is stronger than humans.

Has our painter already decided in 1930? No one will ever know but the painter’s artworks, often messianic, talk for him.

In 1931, Le Pho will leave for Paris, and live there for more than a year, also visiting Europe, before returning to Hanoi in 1932 where all seems going well for him. A new posting as a teacher in Fine Arts, a strong group of collectors, the consideration of all and the ease of his native country.

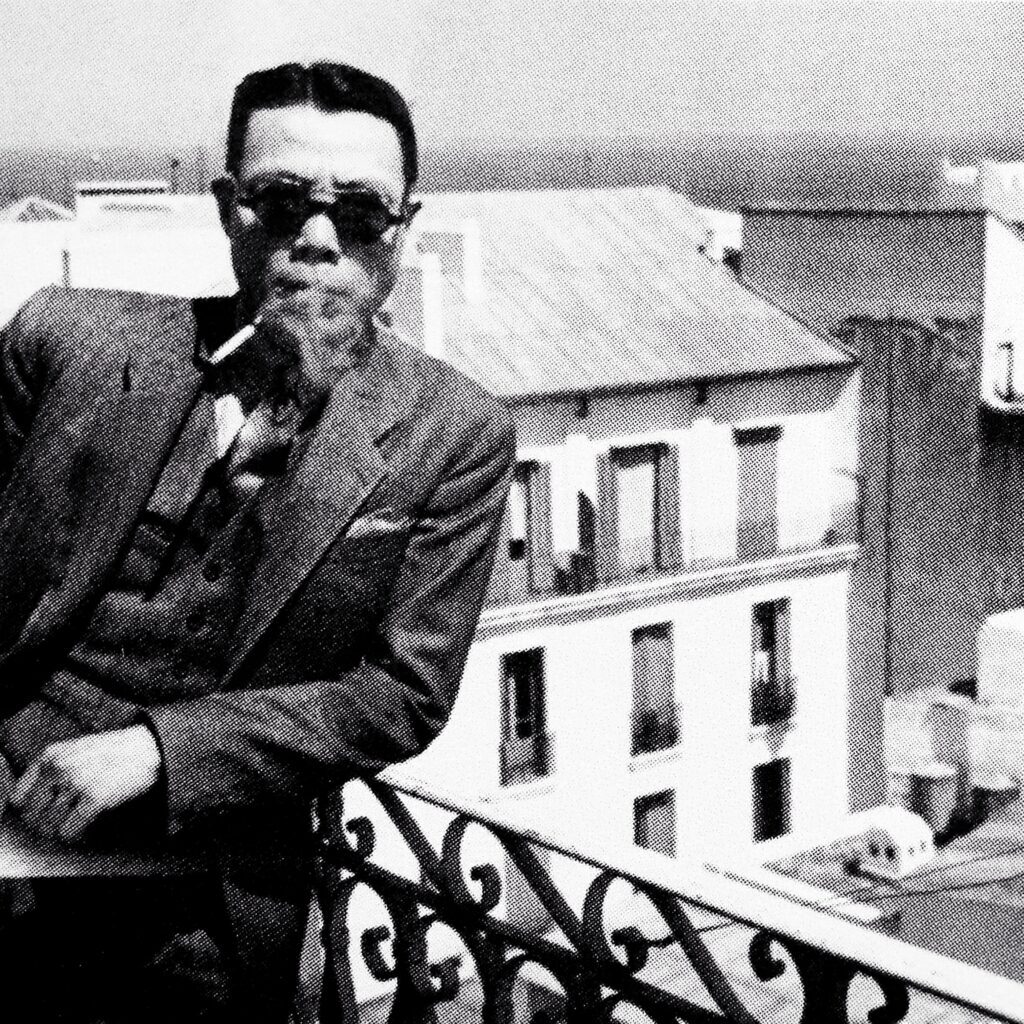

However he knows that the real power in art is in the ville-lumière (Paris). He no longer wanted to address a deceased mandarin world but he wanted to continue his quest for the absolute, following the steps of Bonnard and Matisse.

In 1937, he left Vietnam for Paris and never returned to his native country.

Jean-François Hubert