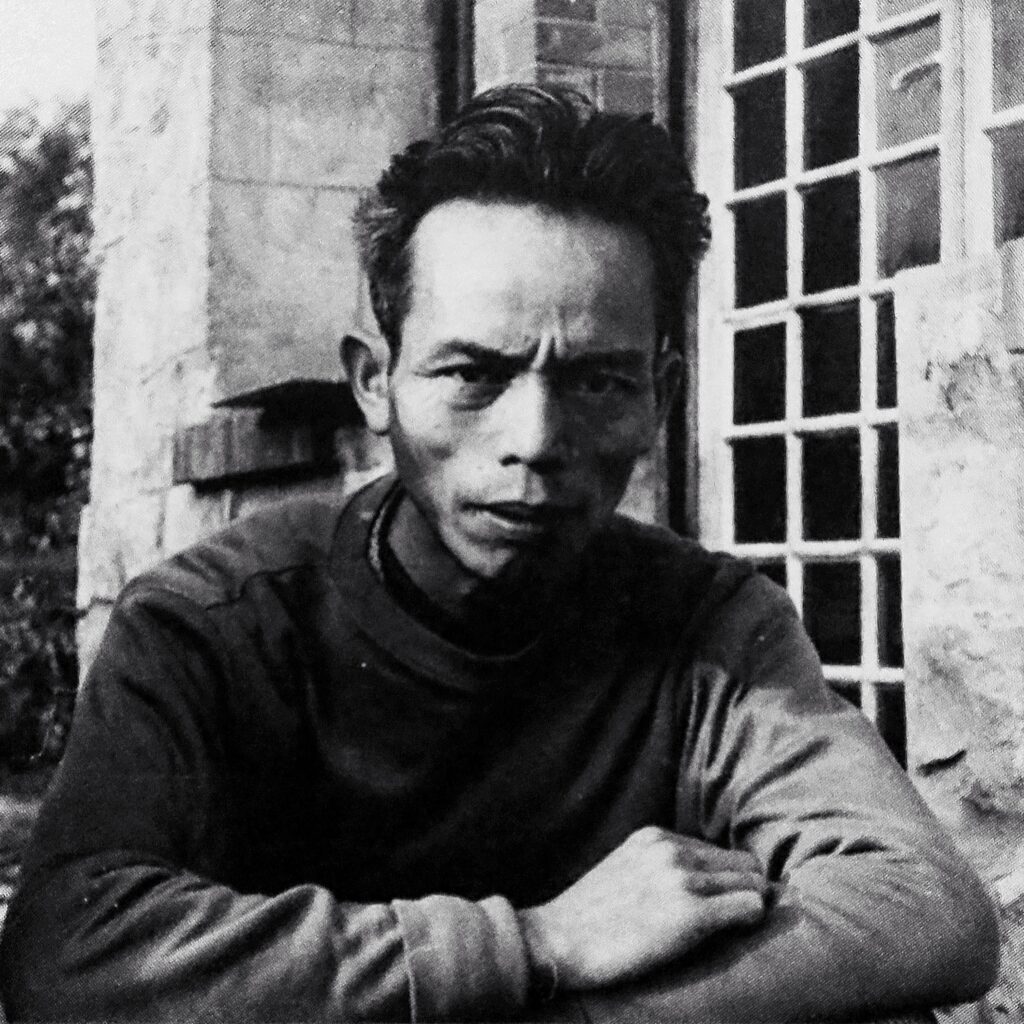

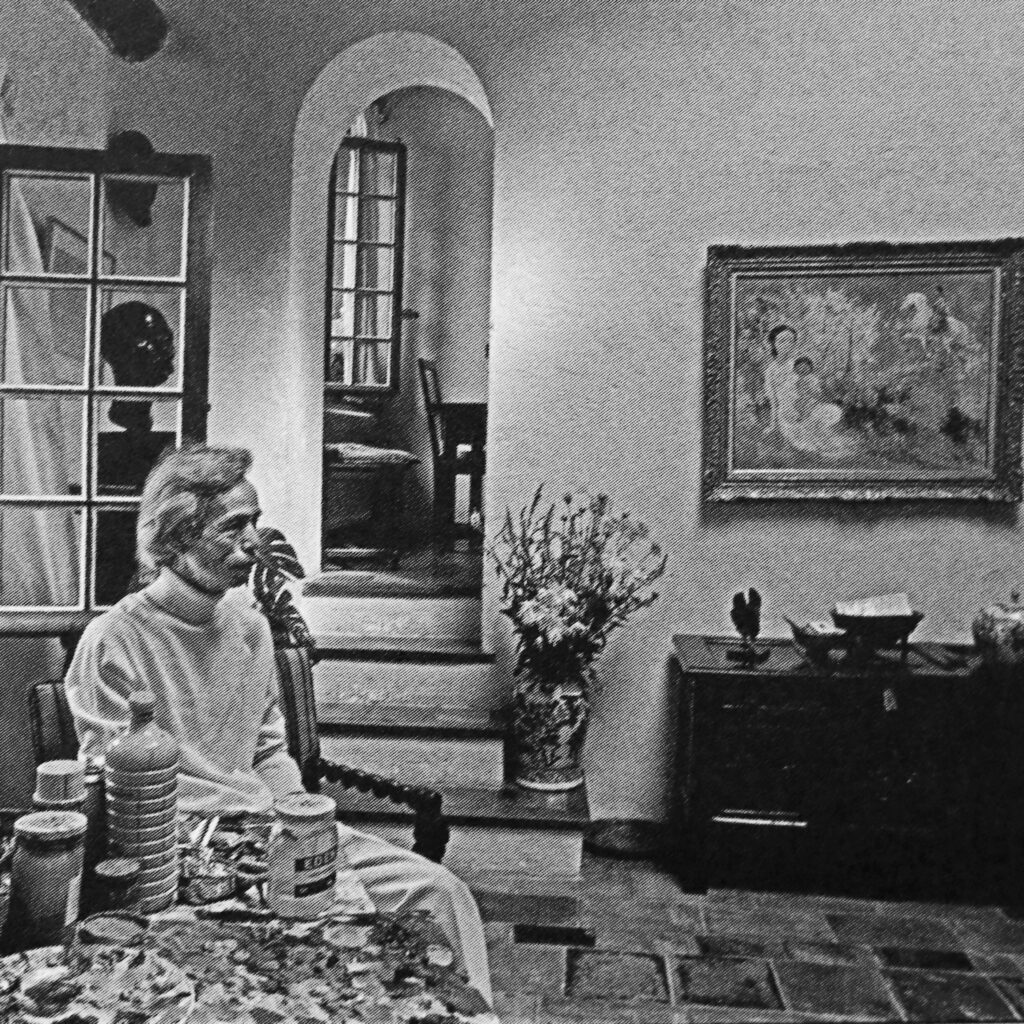

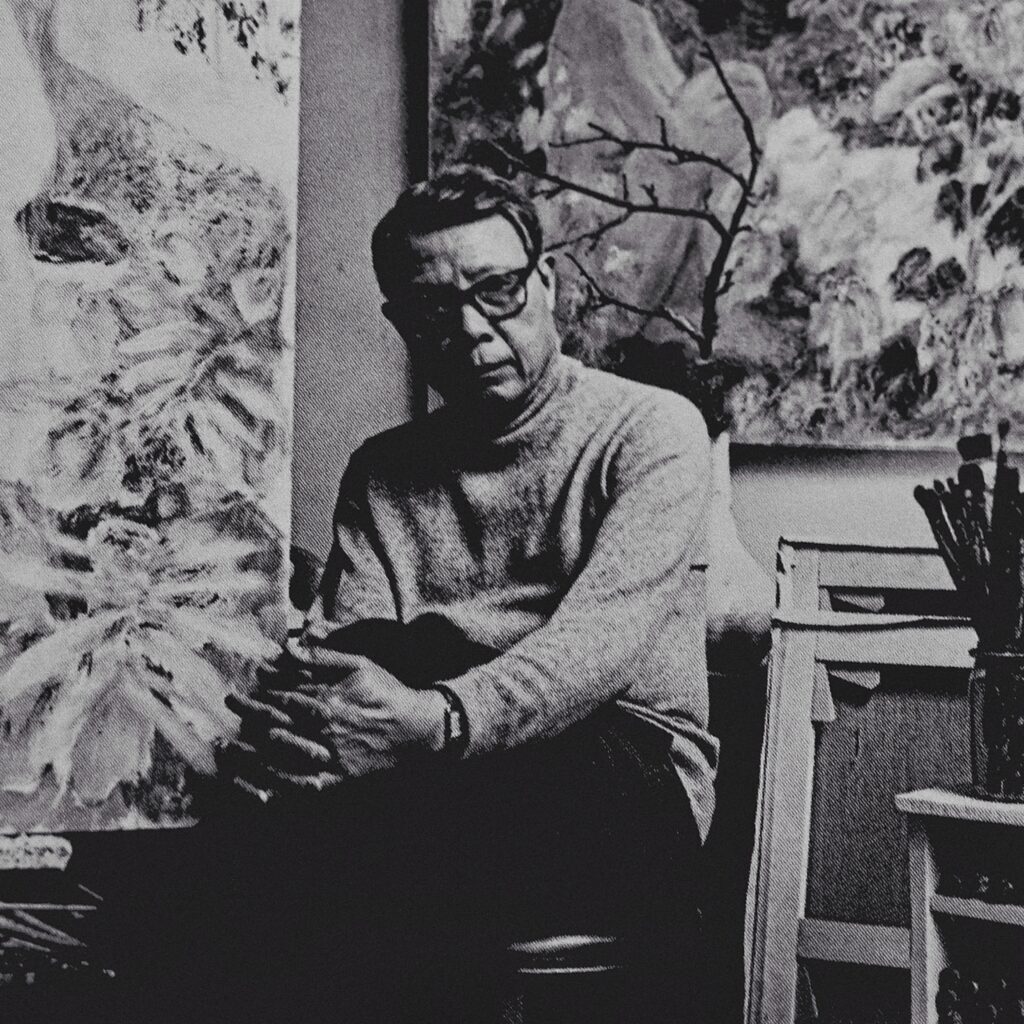

Vu Cao Dam (Vietnam, 1908-2000)

The Cheo Actor

Signed and dated '40 lower right

Ink and gouache on silk

39.5 x 25 cm. (15 1/4 x 10 in.)

painted in 1940

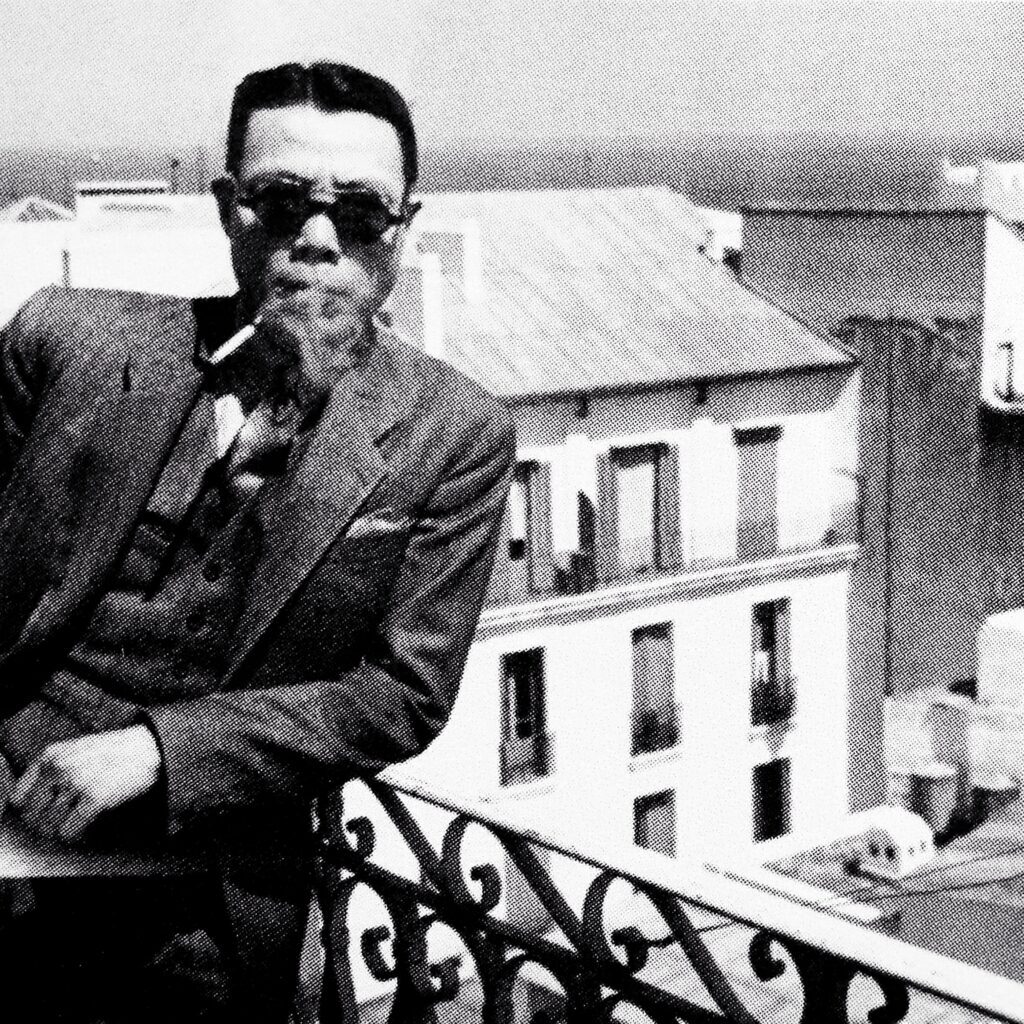

When he painted this gouache and ink on silk in 1940, Vu Cao Dam was already living in Paris for nine years.

In this terrible year 1940, it is very difficult to date exactly the work.

“40” was the year of all hesitations (“The Phoney War“), of all tragedies. And above all, of all renunciations. The absolute and terribly humiliating defeat of the French army against Germany happened so fast and only 22 years after the armistice of 1918, the price to pay for lack of preparation before the conflict to come.

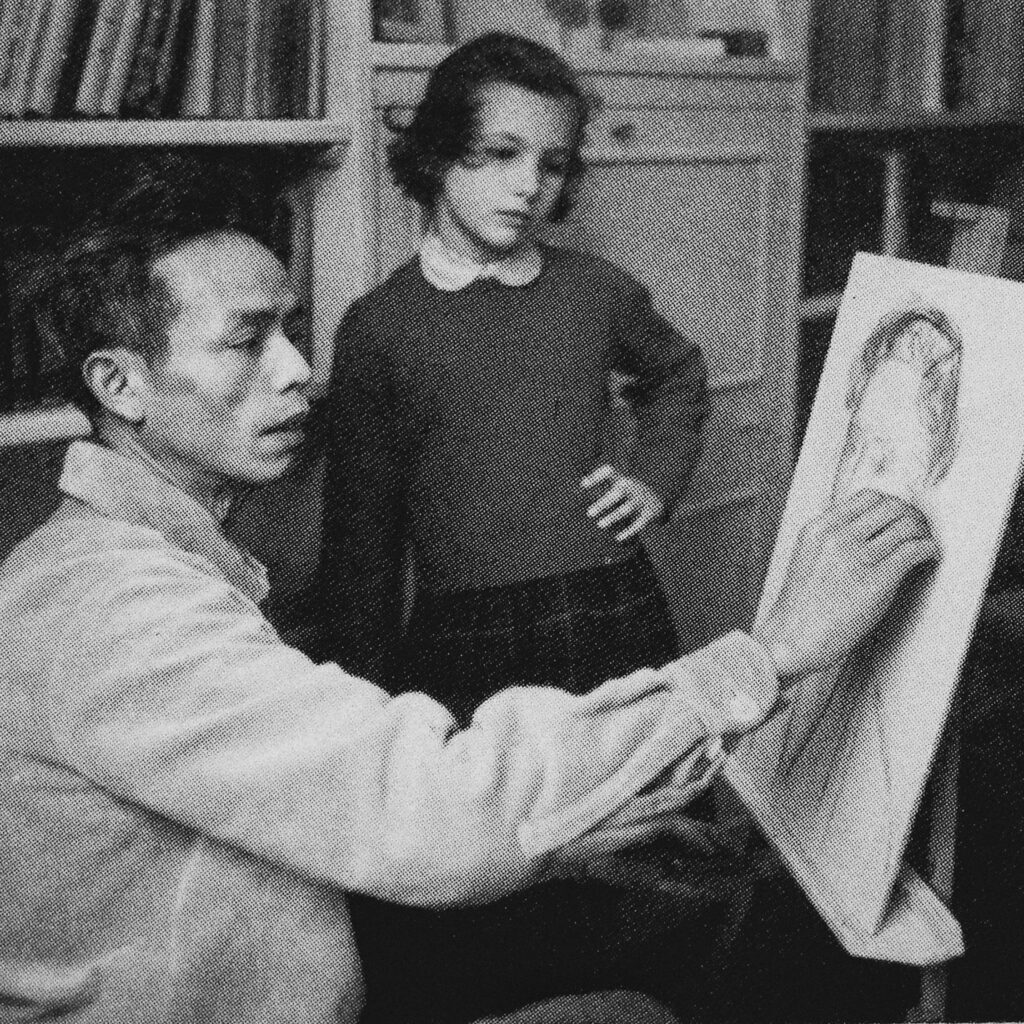

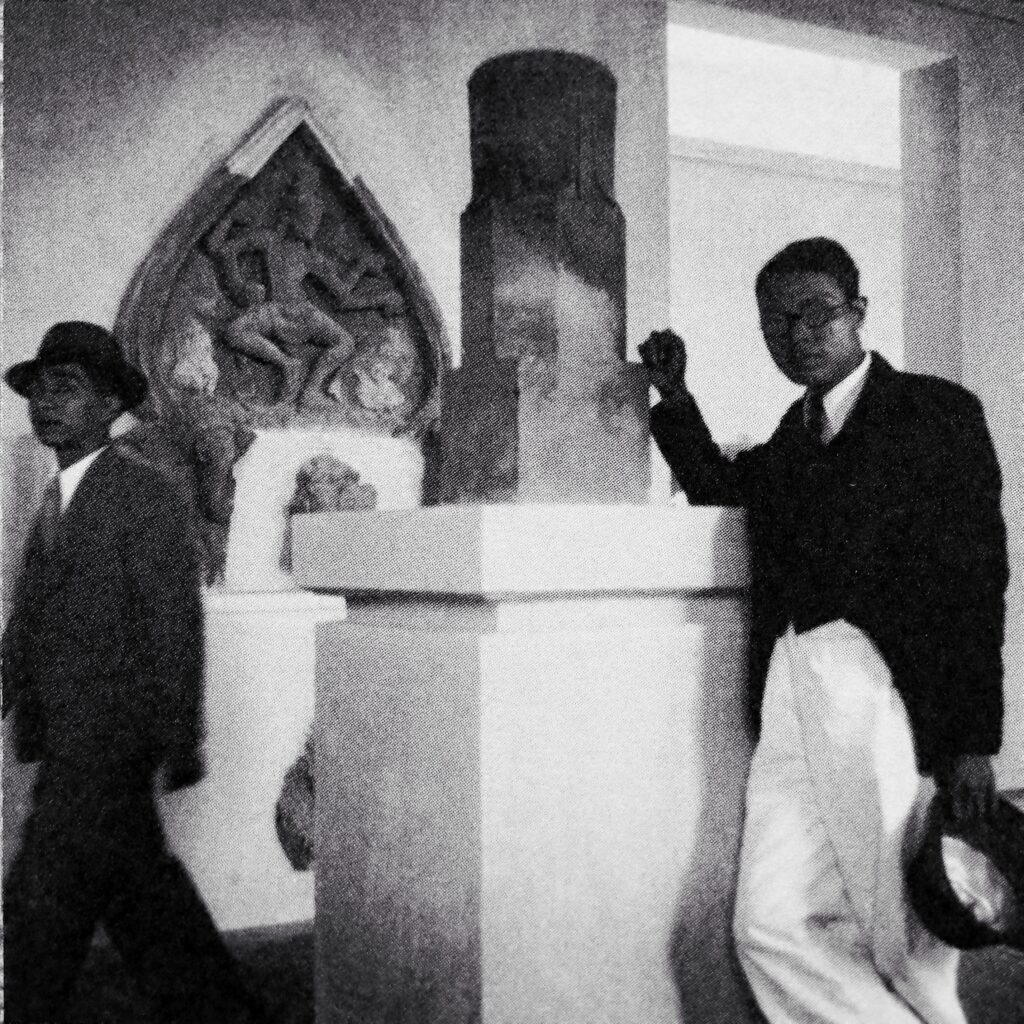

Since arriving in France in 1931, Vu Cao Dam has become an emancipated artist: The Colonial Exhibition of 1931, the Universal Exhibition of 1937, his marriage with Renée Appriou in 1938, his participation in the hectic collective artistic work based on Montparnasse’s style, all of that made him an independent artist. The country of his birth became more of a memory than a reference.

The chèo is a popular theater from northern Vietnam, originally played in the countryside or the courtyards of communal houses and pagodas, becoming more urban at the end of the 19th century… while acquiring at the same time the clear influences of French theatre: establishment of the act, the stage, precise dialogues, refined stage play, diversification of characters.

Stories of simple everyday life, traditional tales and legends, always told through the prism of comedy, the chèo is a moralism. Incarnated by different characters reappearing according to the representations and immediately identifiable by the public as Hè, the jester (its translation in Vietnamese), the comic element. It is probably the character Vu Cao Dam proposes to illustrate here.

There are as many styles of chèo as there are performances, but let us schematise: traditionally, a simple carpet was used as a stage with the audience occupying three sides. This public is active, calls out to the actors, makes comments as if they were the actors themselves, and reactivates the play if needed – the action.

Today we would speak of “inclusive” theatre…

A set, very simple, but a more complex musical environment: a wind orchestra (flute), a string orchestra (two-stringed viola, monochord, round-box and two-stringed lute), and a percussion orchestra (drums and cymbals) accompany the actors. A choir, composed either of the musicians themselves or of the actors singing known melodies while they are waiting for their entrance on stage.

The chèo, beyond the farce, is a moral: honesty, fidelity, filial piety. Good must be rewarded, evil must be punished.

The gestures of the actors, codified, and their mimics, exacerbated, must translate feelings identifiable by the informed public.

Thus the “virtuous woman” walks in a straight and dignified manner, while the less “virtuous” one wanders provocatively, undulating her hips, on either side of the stage.

The character of Hè, make-up made of black, most often dressed as a valet, does not just comment the action but also reprimands and warns the passing Mandarin – or any other authority – with the vocation of ridiculing them. Originally the chèo consisted of five typical characters. Hè, our buffoon, “Lao” (the comrade), “Mu” (the telltale), “Thang” (the guy), “A” (the chick). These have become more complex (“Hè Moi”, the talkative buffoon, “Hè Gay”, the buffoon with a stick, among others) or revealed as “Phu Ong” (the rich man) or “Thua Tuong” (the Great Mandarin), among many others.

It is interesting to note that Vu Cao Dam invokes and favours the chèo, a popular and intrinsically Vietnamese theatre, over the classical theatre, the “tuồng” (classical theatre totally Chinese in essence), dominated by the lessons of the past and the great historical themes, specifically Chinese (“History of the Three Kingdoms”) or Vietnamese (“The Trung Sisters”). The painter could have illustrated a scene from Kim-Vân-Kieu, part of the classical theatre, already often illustrated directly or indirectly in his work. Let’s specify that the Thach-sanh or the Luc-vân-Tiên, classic among the classics for every literate Vietnamese, are also part of the classical theater repertoire.

The choice of the buffoon’s character is revealing of Vu Cao Dam’s mentality in this year 1940. First of all, in the chèo, the jester is central to the representation and is the much-waited character. He is key to this theatre because his character is the one transcending reality, even if it is simulated. The jester laughs when he is sad, cries when it is funny. The jester is the publicist of the absurd, the conqueror of the infinite emptiness that assails us.

In chèo, the self-deconstruction of the artist by himself is twofold: he frees himself from the Chinese legacy and follows a French way through the Vietnamese vector.

The color black floods the painting: Hè’s face, of course, but the green background, the shirt that we would like to see white. One might think – but it is not certain – that the painter dipped the silk in diluted ink, as it was the custom at the time, but in this specific work the density of ink in the water was greater than usual. And, of course, an even darker black is applied for headdress with, also, some green and white gouache. One will also note the features of our jester, skillful compromise between the silliness of the facade and the necessary percussion of the temperament.

In this year 1940, Vu Cao Dam, René’s fulfilled husband of two years, who had been living in France for nine years, went to look for the most emblematic actor of the chèo to let us know that, in a life, there are no serious answers to pointless questions: we are free to suffer. But we suffer from being free.

He has just realized that if everything that can be formulated is false, not everything that is visible is necessarily false. He, the Confucian, breaks all certainties in this emblematic picture.

But we already knew it: an artist is not a social being.

Jean-François Hubert