Nguyen Do Cung (Vietnam, 1912-1977)

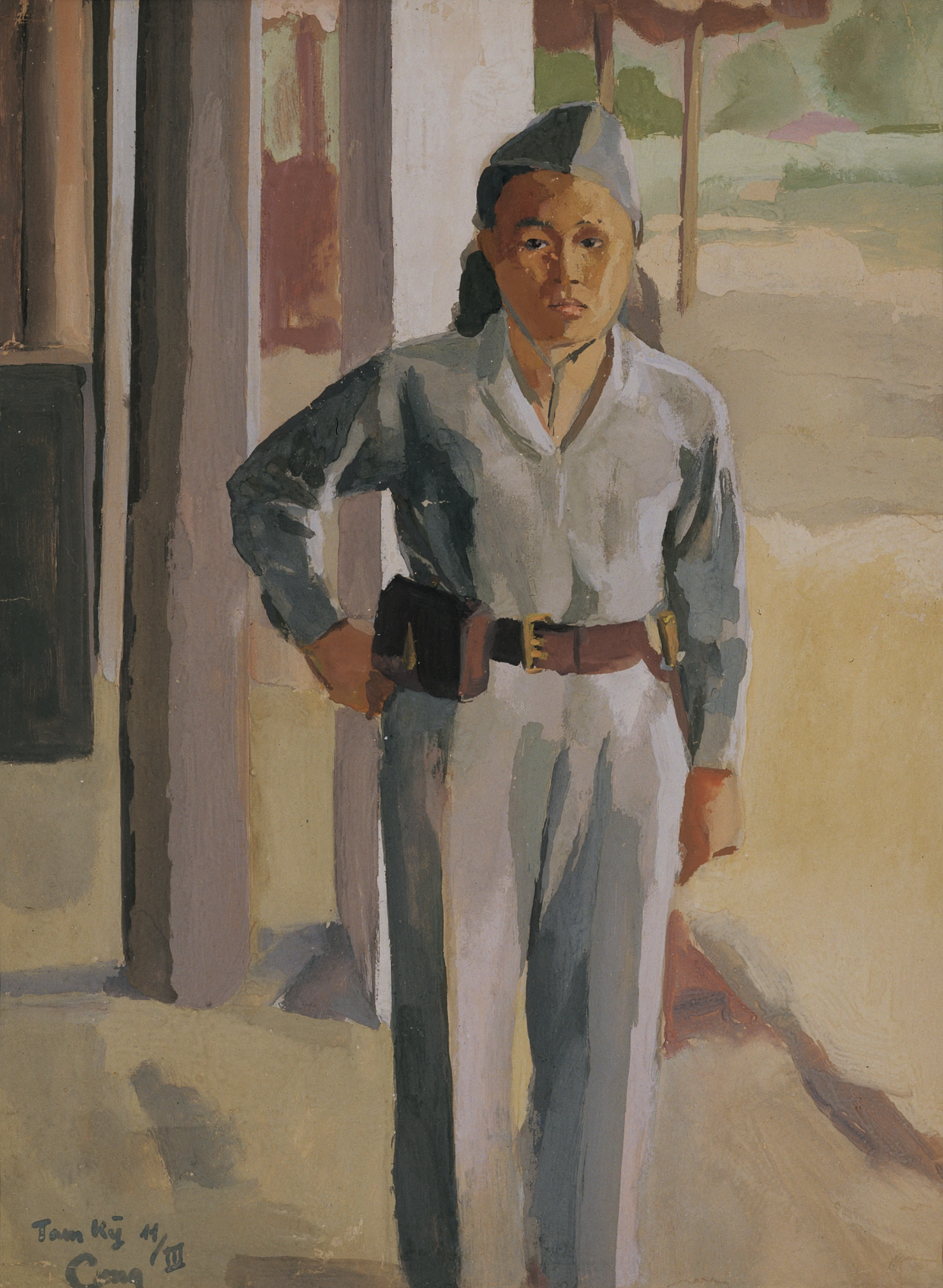

Le Combattante (The Combatant)

signed and dated 'Tam Ky 11/III' (lower left)

watercolour on paper

55 x 39.5 cm. (21 ½ x 15 ½ in.)

Painted on March 11, 1947

LA COMBATTANTE (THE COMBATANT)

OR THE BO DOI'S SOB

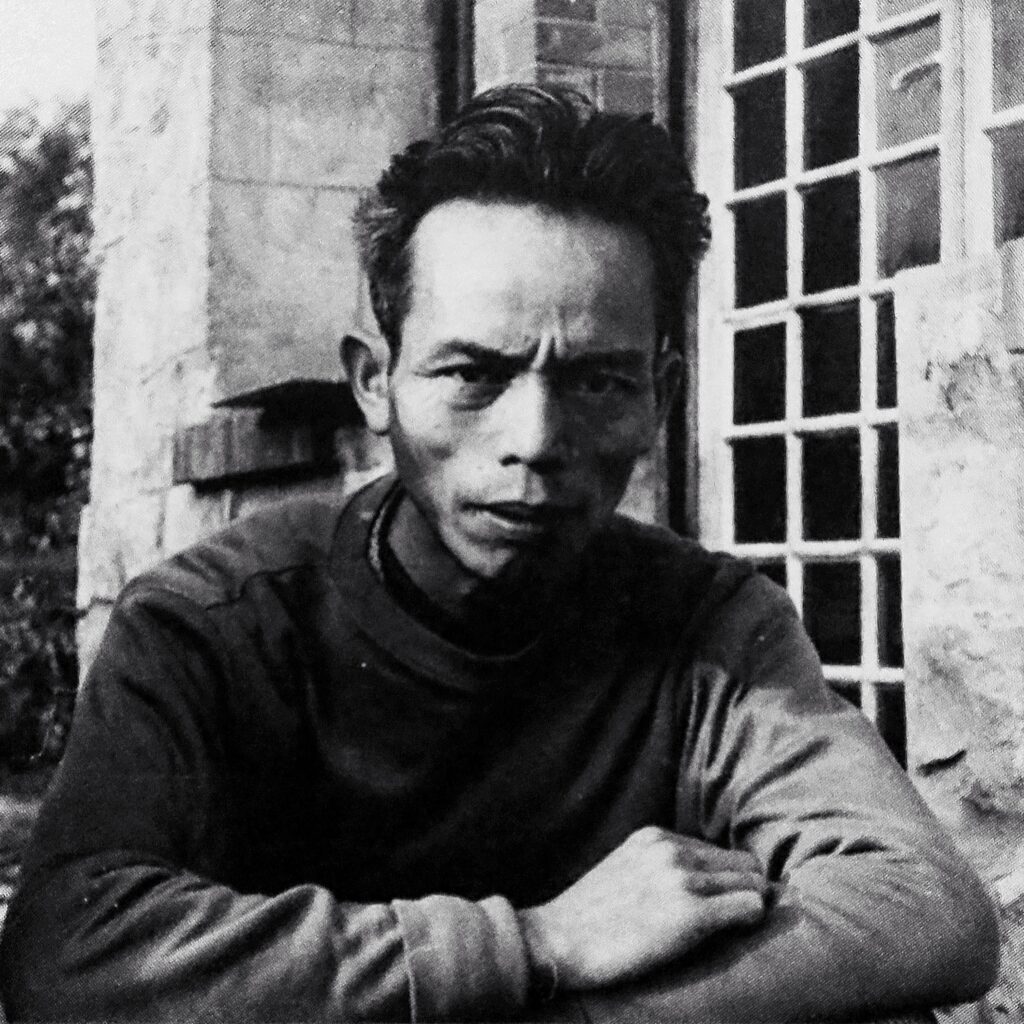

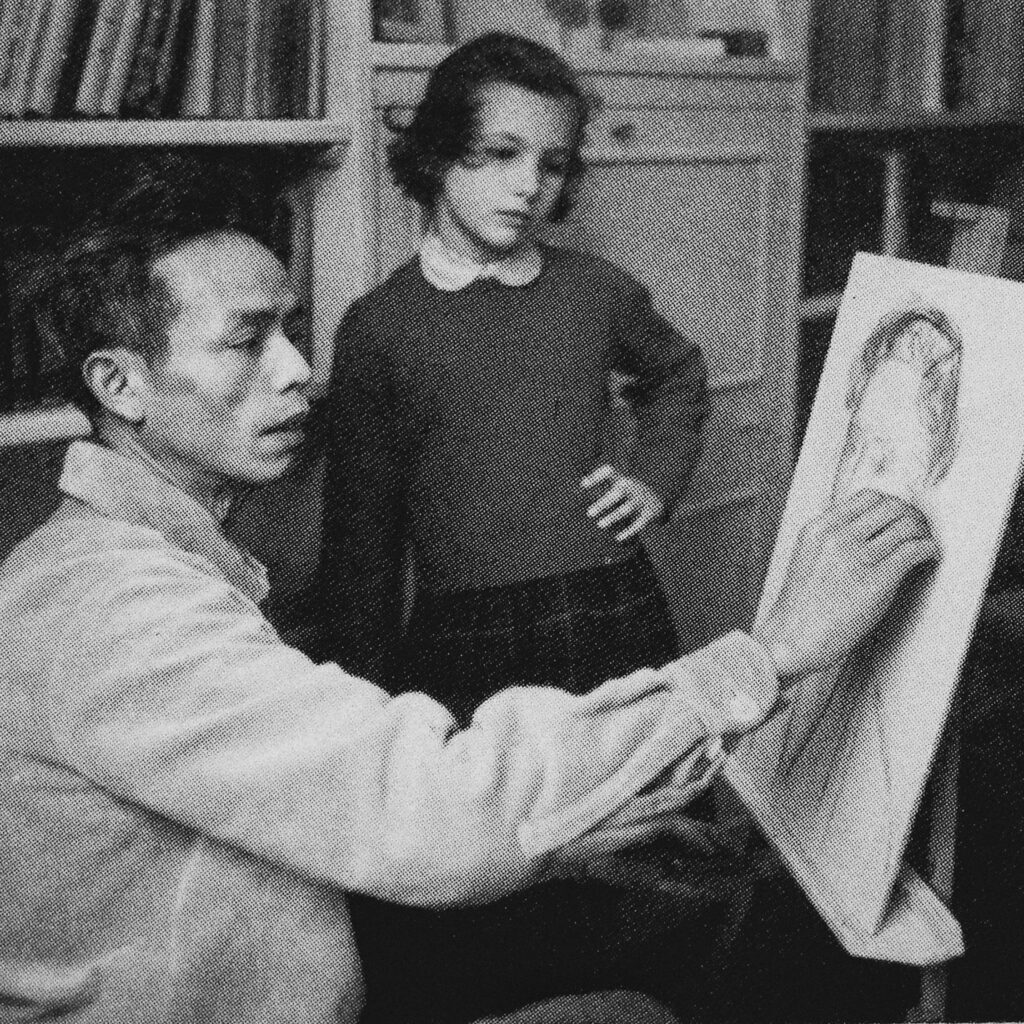

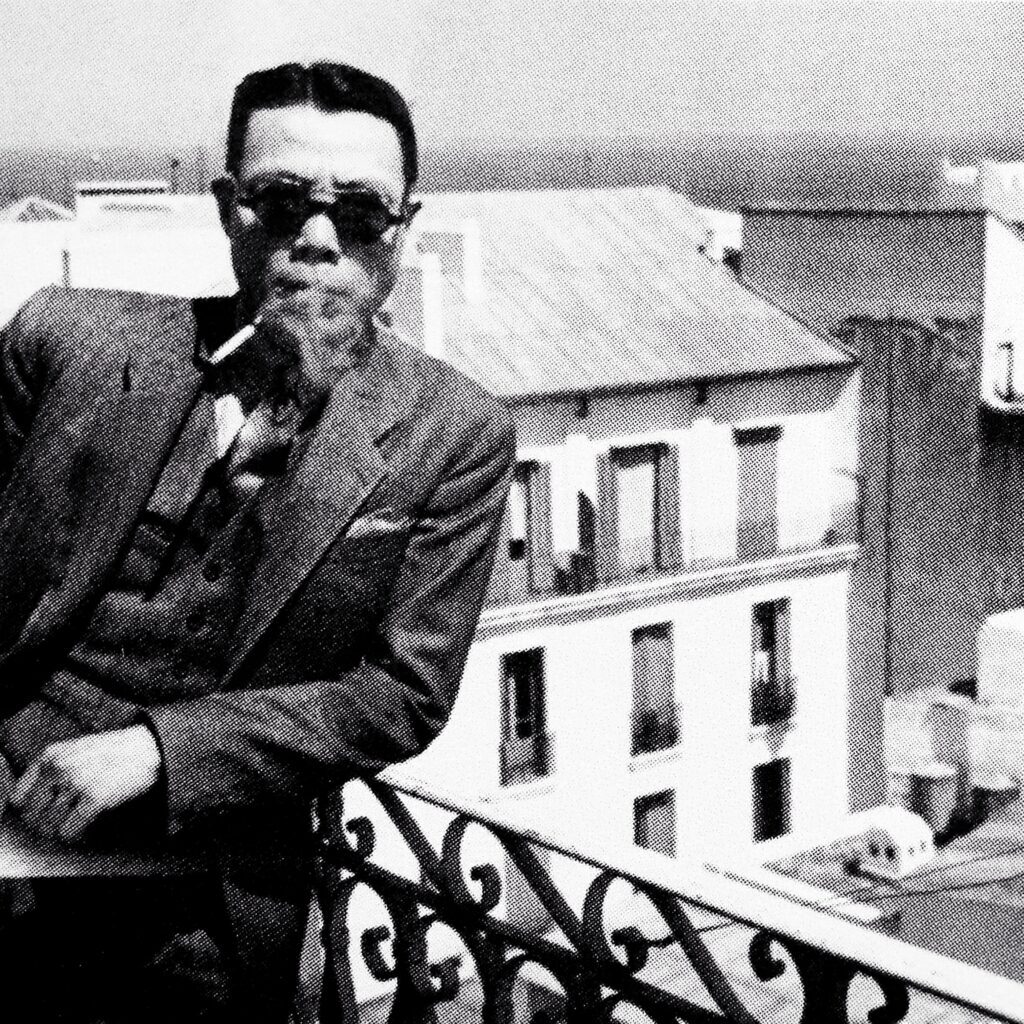

Born in the village of Xuan Tao, in the Tu Liem district of the Hanoi suburbs, Nguyen Do Cung (1912-1977) was the son of Nguyen Do Muc, a learned Confucian and translator of Chinese novels. He graduated from the School of Fine Arts of Indochina in Hanoi with the fifth class in 1934 along with, notably, Tran Binh Loc and Pham Hau.

Nguyen Do Cung was not only an artist, he was also a theoretician, the author of articles detailing his research and codifying his conception of artistic creation. Him and his friends writers and artists-Pham Van Hanh, Nguyen Xuan Khoat, Nguyen Luong Ngoc, Nguyen Xuan Sanh and Doan Phu Tu – will publish in 1942 in “Spring-Autumn Archive Spring-Autumn Anthropology” texts written since 1939 under the same name of Xuan Thu Nha Tap. The book includes a number of poems, philosophical prose and an artistic manifesto of the group (some of the texts were previously published in Thanh Nghi newspaper). That group all the way to 1945 wanted to innovate and create a new phase within the “New Poetry” movement.

Maurice M. Durand and Nguyen Tran-Huan in their “Introduction à la Littérature Vietnamienne” (Introduction to Vietnamese Literature) (Paris 1969) indentified (up to 1962) in a “synoptic table » nine periods (pp 110-111) including the Xuân Thu Nhã Tập (with the Hàn Thuyên, the Tri tân and the Thanh Nghị) in the sixth period from 1935 to 1945. According to them, it corresponds to the « decline of the Tự lực văn đoàn, (to) the development of the Roman Réaliste, (at the) birth of revolutionary literature with a Marxist tendency, (at) the return to Antiquity ».

Our authors judge very severely (p130) the poets of the group… “whose poems, incomprehensible and hermetic, were influenced by French symbolic poets such as Mallarmé, Valéry, etc… (…). This group’s manifesto, using high-sounding but meaningless words, spoke of “the Supreme Intellect”, “Eternal Art”, “Permanent Music”, and “the effort to arrive at oneself – even by the rhythmic and harmonious ways of Literature by Art, and above all by Poetry“…

Vast program, certainly…

The August 1945 Revolution brought Nguyen Do Cung’s drive for emancipation in all domains to its highest point. In 1946, he painted the portrait of Uncle Ho in the Presidential Palace in Hanoi, so did To Ngoc Van and Nguyen Thi Kim, before leaving town.

The following years, 1947 and 1948, he staid in the southern part of central Vietnam, where the land is a narrow, arid band under a strong sun, where the people are frank and open. He lived and painted there in infinite joy, delivering a set of works executed when he fought the French colonial authority with Vietminh. The whole region more than a maquis was an area practically controlled since 1945 by the Vietminh.

An adept of realism, he gave many of his works to military engineers, to workers making parts of hand grenades, to the factory producing weapons for the front. His works show well-known places: La Hai, Bong Son, Nho Ban, Cao Thang, An-Khé, Tam Ky… Their titles speak for themselves “The Weapons Factory”,”The Front at An Khe”, “TheTiger’s Hole in An-khe”, “The Destruction of Phu Phong”, “Self-defense in Tuy Hoa”, “Scene of Daily Life in the Fifth Strategic Zone”, “A volunteer to the South” or “Guerilleros at Target Practice”, all gouaches in warm browns, in tints of light pink and soft white offer us a subdued view of war, far from the stereotypes of the genre.

Our watercolor on paper (55 X 39.5 cm) dated March 11, 1947 and located in Tam Ky (Quang Ngai). The fighter, in military costume, displays a hieraticism that seems to have been acquired recently. Here reigns the realm of austerity. Everything is vertical, from the pleats of the trousers to the columns of the building. The drawn face of the fighter expresses a hardness where fatigue competes with the revolutionary spirit.

After these testimonies on the war effort Nguyen Do Cung will embark on the representation – obligatory… – of the peace effort. One must say that the indescribable Nguyen Quang Phong, mediocre painter but official art historian of the regime, did express himself in a text from “Vietnamese Contemporary Art” (Hanoi, 1996, pp 250-51), of which I prefer to give the exact transcription of its original text: in a few words, an entire ideology, with its devastating pettiness, is summed up.

“Nguyen Do Cung had a high ideological level and often reasoned by paradox. He made a rather severe self-criticism about his views in the French days: “At that time, I painted only as I desired, I did not care for those who did not understand me. It was terrible… Now we are working for the large masses of people. We must paint in a way understandable to the masses so they love our paintings”. Abandoning cubism that he had introduced into Vietnam, Nguyen Do Cung endeavoured to reflect faithfully the objective realities, to render seriously and clearly in his paintings the scenes of the life in the resistance, with cadres going to work, workers turning out weapons, guerrillas in shooting exercises, soldiers in march… There were beautiful pictures, but some fell into naturalism. For instance, it is wondered why Nguyen Do Cung presented a dog crossing the roadbed in a street of Physical Phong where everything had been destroyed to cope with the enemy during the resistance: what is the meaning of this painting which translates such a trite sight? However, under the new regime, everyone agreed with Nguyen Do Cung and shared his point of view of ‘putting oneself at the service of the masses’. One admitted that it was difficult to concretise this point of view by actions, but one must strive to do so, because it was one of the three attributives of Vietnamese culture: national, scientific and popular.“

We understand better the terrible ideological oppression exerted on the artist who was nevertheless officially praised by Ho Chi Minh himself in 1948 as shown in the document (Dogmatism is always schizophrenic).

In 1962, he became president of the newly created Academy of Fine Arts.

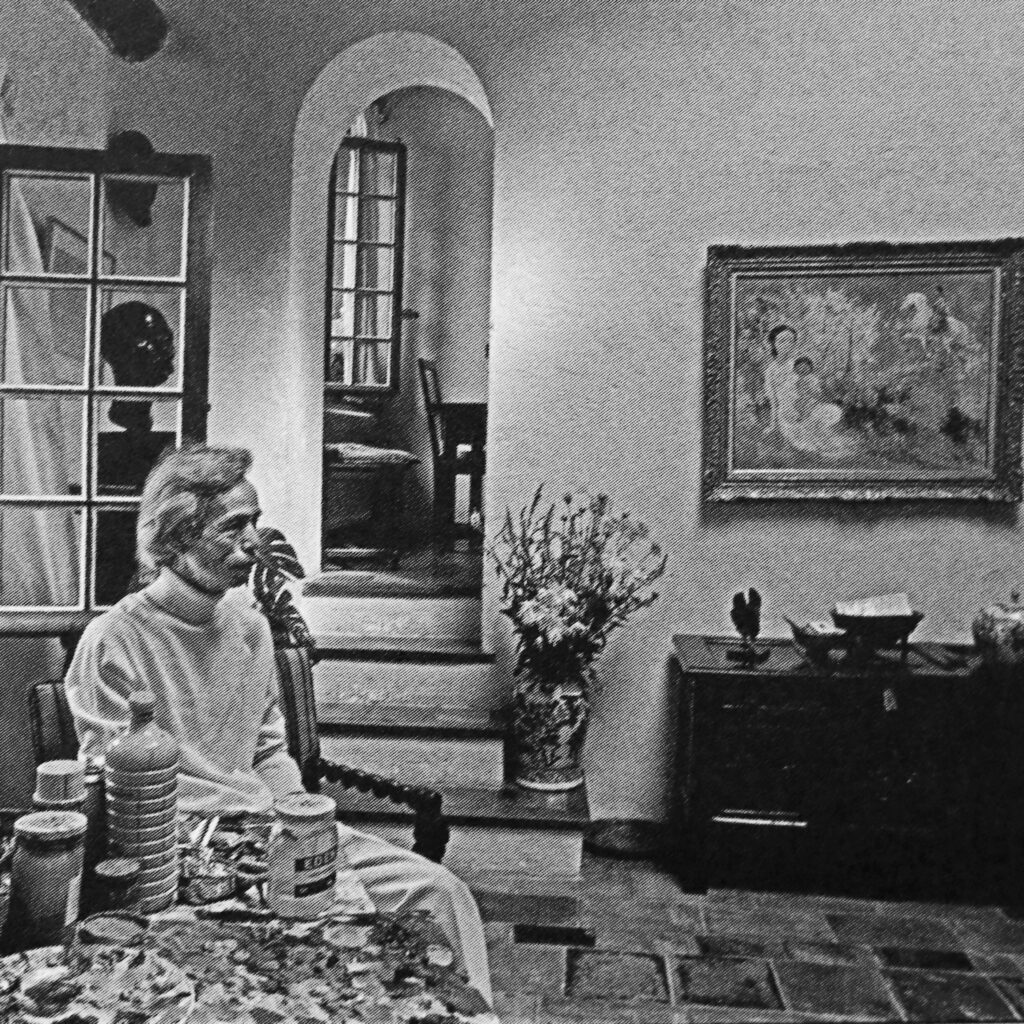

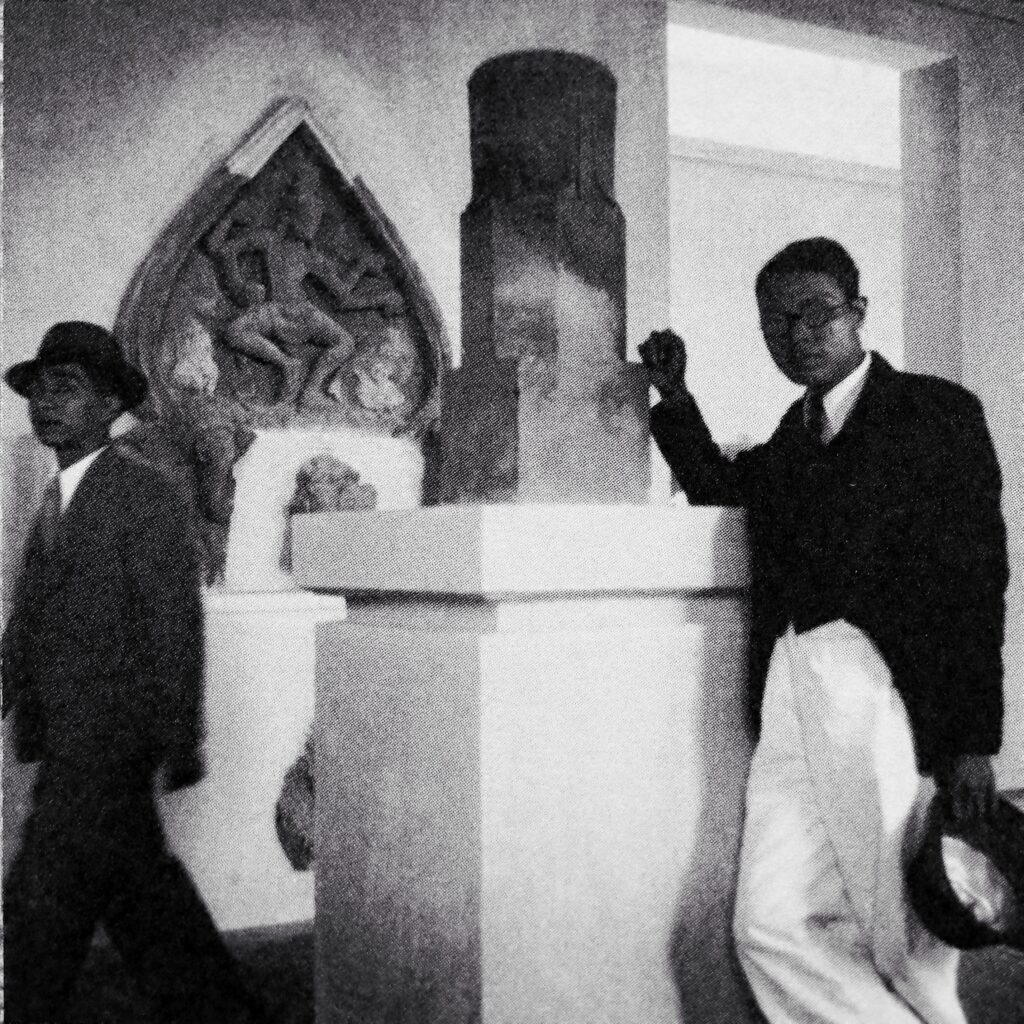

He was then given the responsibility to determine, assisted by a group of colleagues, the foundations of the future Museum of Fine Arts, in Hanoi. The magnificent house (former colonial high school and boarding school for young girls) Lycée Jeanne d’Arc – at 66 Nguyen Thai Hoc Street was laid out into an exhibit hall.

All without giving up his career as a painter as we can see, among others, with his “The machine building workers” an oil (67 X 92 cm) dated 1962 and found today in the Hanoi Fine Arts museum.

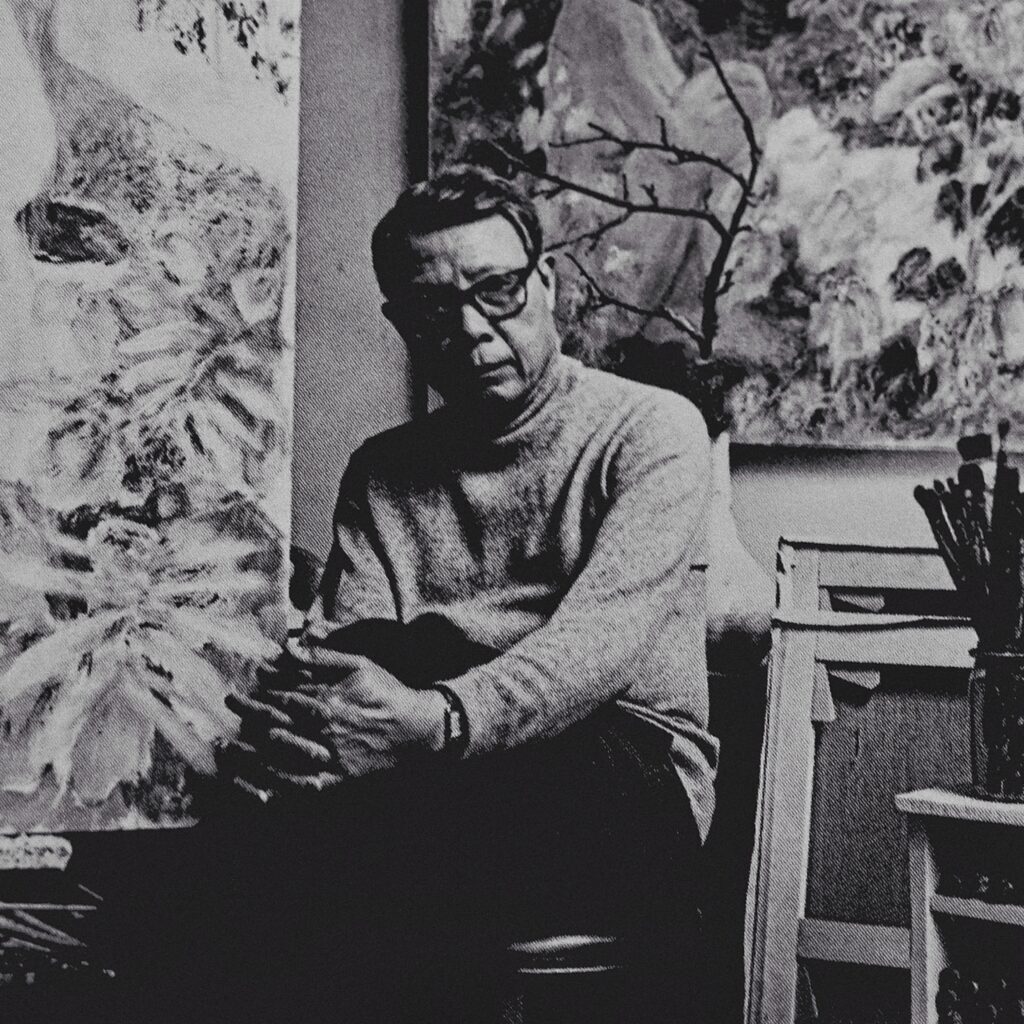

The painter executed several preparatory works we had in hand. Among them, was this pencil and watercolour, particularly interesting for its original handwritten annotation upper right. It should be noted that the painter writes in Vietnamese, no longer in French, and that he refers to “Te Bach Thach” the Chinese painter better known by his Chinese name Qi Bai Shi (1864-1957).

Avoidance of the French language and reference to Chinese painting : a trend of Vietnamese painting we already mentioned…

The text in Vietnamese:

« giấy và thuốc này có thể là

vẽ đến đâu được đến đấy

– Do đó không nên vẽ dầu

từ toàn thể, mà nên

vẽ như Tề Bạch Thạch

– Nên đi chevalet và

vẽ mầu “khô”, sẽ

tươi thắm và “voulu” hơn »

The English could be :

“Paper and substances are applied gradually as it goes on

– Hence, don’t use oil on the whole, it should be painted as Artist Te Bach Thach did

– Utilize chevalet techniques and “dry” pigments will (make the painting) be more freshly deep and desired“

On the other hand the museum will open its doors in 1966. Its painting section will gradually benefit from many painters’ donations including “second versions” of important works. These are earlier versions offered by the artist to the museum.

Unfortunately, many of these works (originals or “repetitions”) have been stolen and replaced by copies, the originals being often found today on the walls of opulent buildings a few hundred meters around the museum. Let us add that from the beginning, with a laudable goal of educating visitors, the museum wanted to acquire works, unfortunately inaccessible. To do this, it had mediocre copies made which, presented (without great conviction) as originals, have forever vitiated the eye of local amateurs and forced some of the successive leaders, compromised, to divert the subject…

Nguyen Do Cung’s dream has collapsed and local embarrassment is confined in the attempt to hide – until today… – this terrible reality which the Vietnamese state they should find a time limit. In this period of political upheaval, fewer and fewer stupid Walter Durantys will defend—with that American smugness—the indefensible.

A style imposed by doctrinaires, a museum that intuitively he already knew to be sullied by ignoramuses, an erudition out of communist time.

Is this what Nguyen Do Cung was thinking when three years before his death he painted this muscular and ambiguous watercolour, dated 24/5/74?

No more uniform, emaciated features, rigid pose, topographic realism of our “combatant”. It is a semi-naked, muscular, demonstrative body, on the edge of what could be a bed in an unreal place that the artist offers us. What is the gesture of the right hand? Upper right, is it a simple blue spot or a flying bird with a stunted tree further away? We will never know. What we can be sure of, however, is the extreme freedom that Nguyen Do Cung allows himself in 1974 in a country that prohibits the representation of the nude.

All these fights for independence, these deprivations, this perpetual disarray, this quest for the absolute to fall into the mediocre world of pretentious dogmatism?

Dignified and therefore almost inaudible, this sob of the bodoi…

Jean-François Hubert