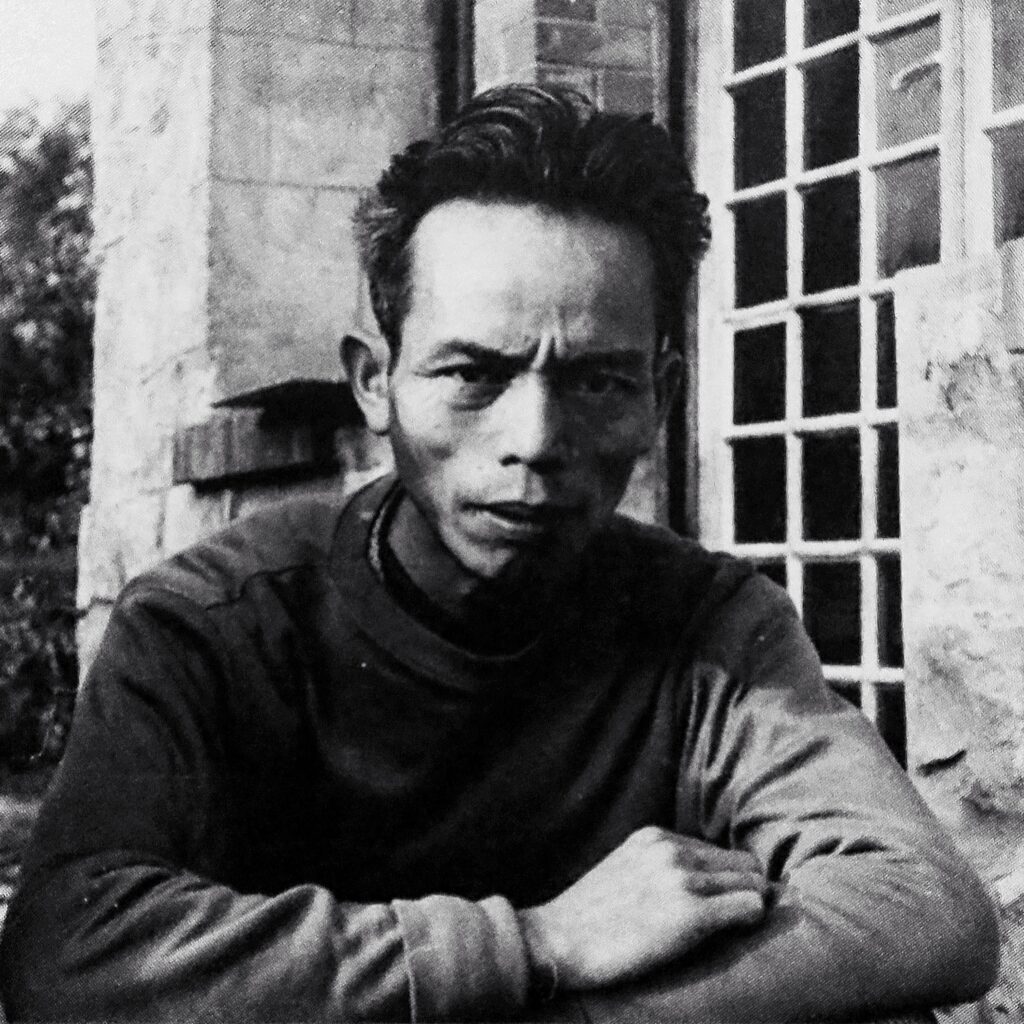

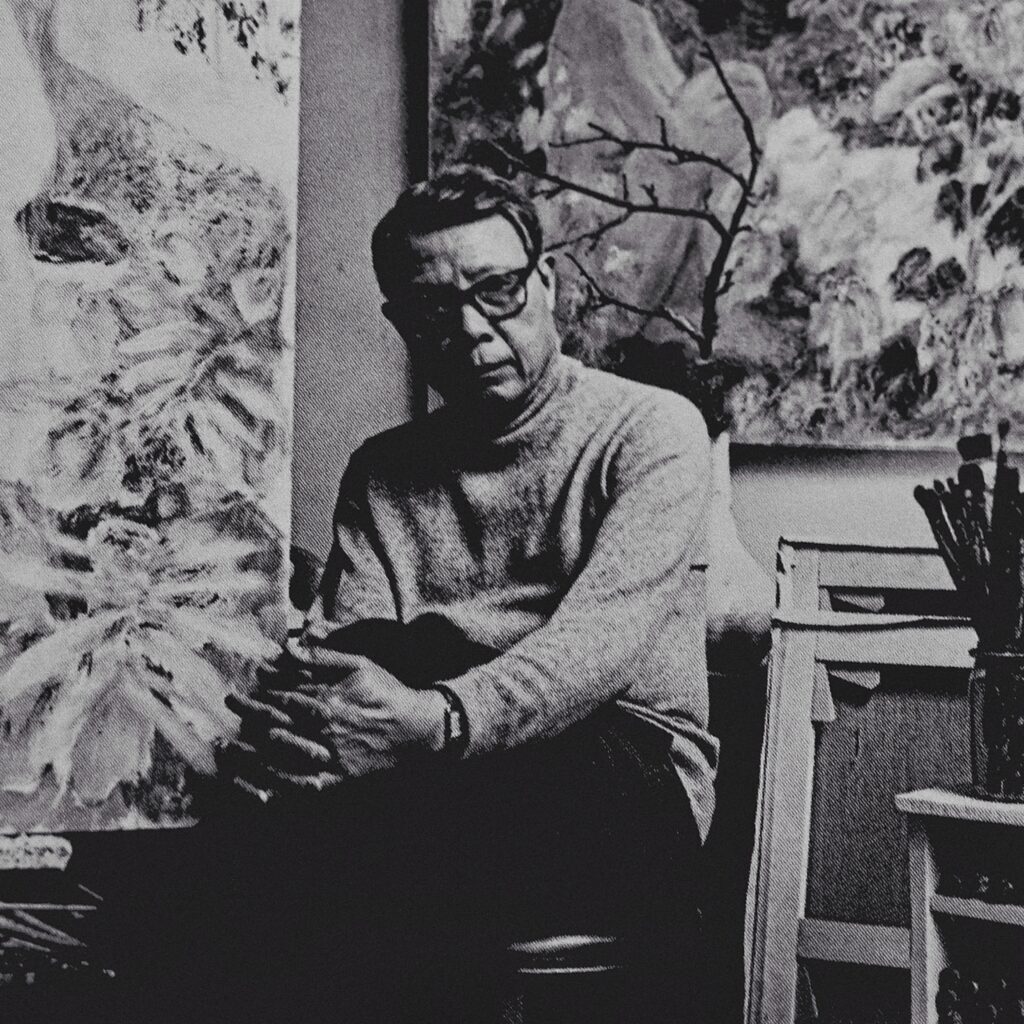

Marc Chagall (Belarus/France, 1887–1985)

Les mariés de la Tour Eiffel (The Betrothed and the Eiffel Tower)

oil on canvas

150 x 136.5 cm.

Painted in 1938-1939

Collection of The Centre Pompidou, Paris, France

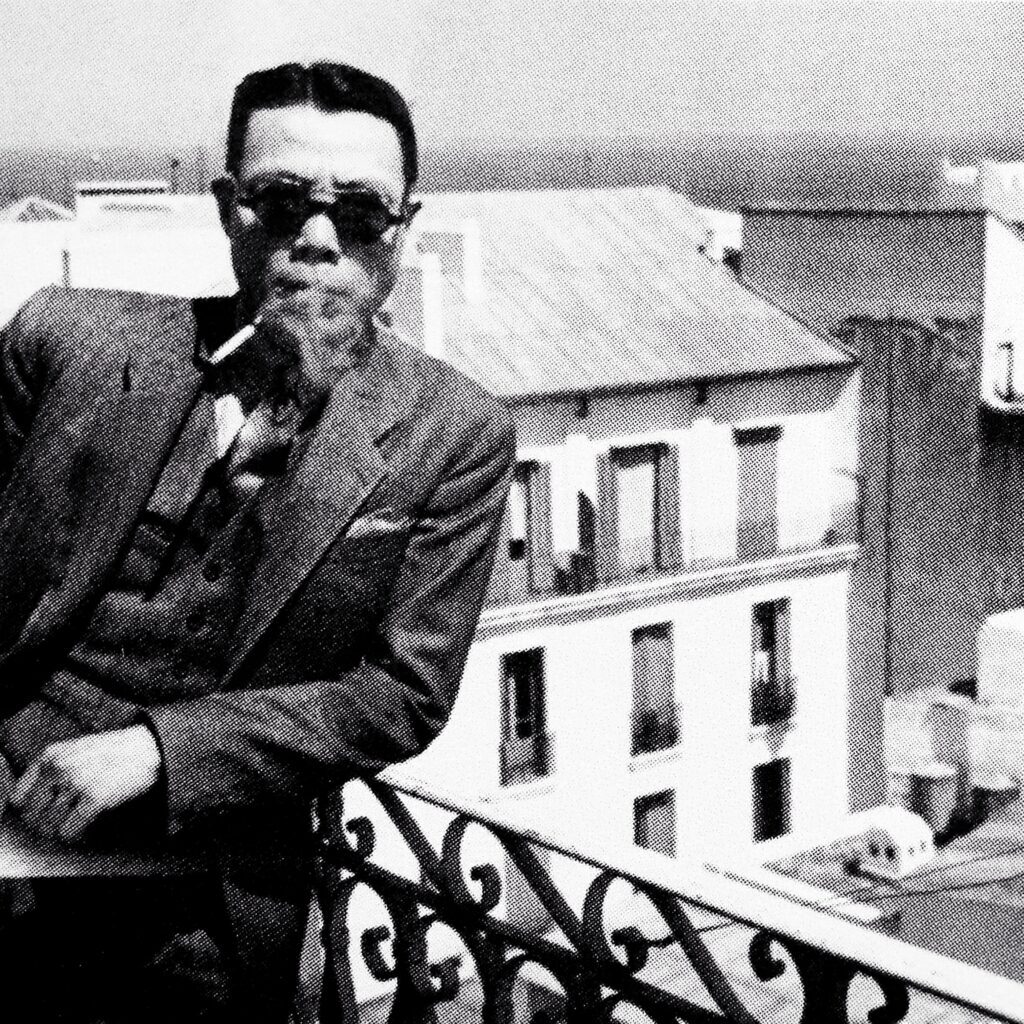

When Marc Chagall painted "Les mariés de la Tour Eiffel" in 1939, the war was close at hand, and the artist didn't rule out the dark idea that this would be his last work. The painting would then be resolutely autobiographical!

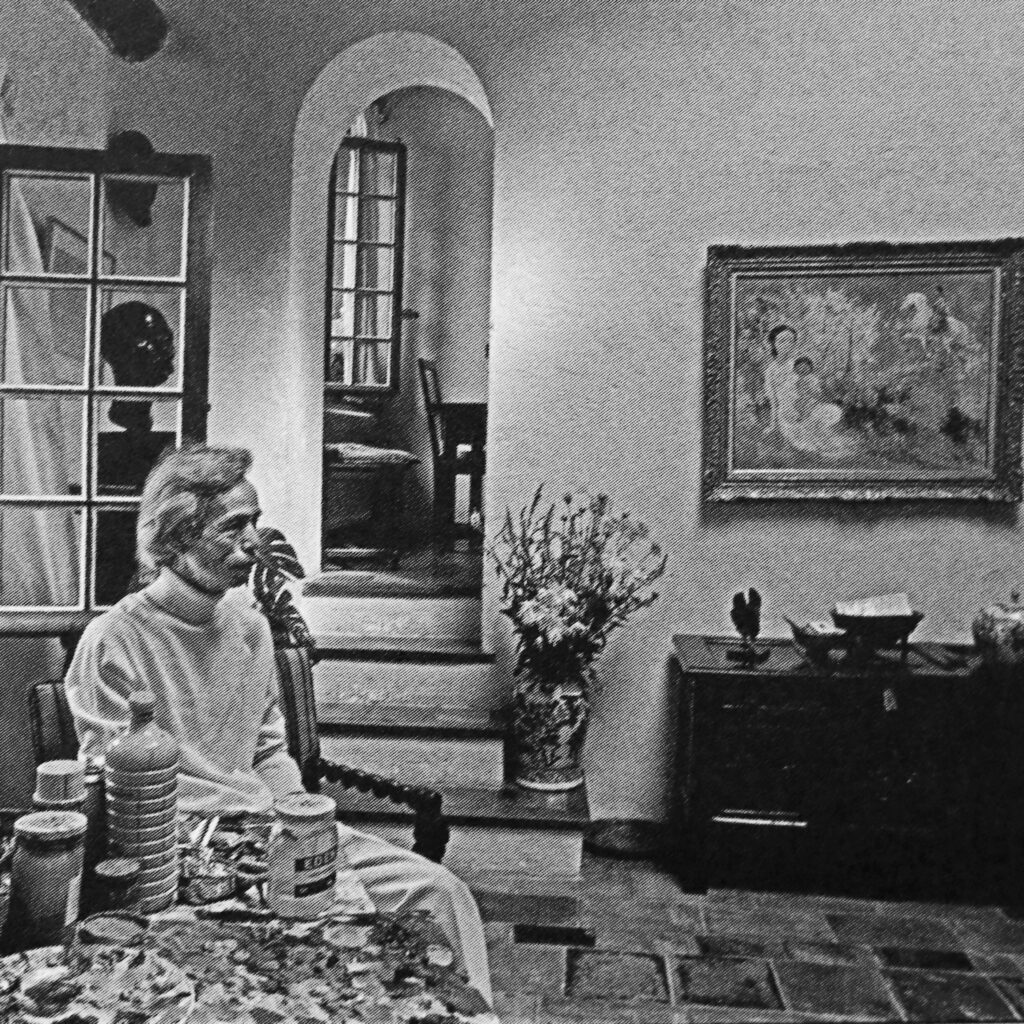

The bride and groom floating strangely in the center of the picture are the painter and his wife, Bella Rosenfeld. They've been married for many years, but their love seems stronger than ever, as evidenced by the husband's gaze on his wife and the arm around her waist.

The artist remembers their wedding day vividly, and depicts it in the left background of the painting, a sign that the event belongs to the past. A warm red and yellow sun illuminates the day. The bride and groom stand under a chuppah, a canopy that shelters the bride and groom in the synagogue.

But beyond these moments of marital bliss, what does the future hold for the couple? The answer may lie to the right of the bride and groom. A small village reminiscent of the shtetl, the Jewish villages of Eastern Europe. An evocation of Chagall's childhood in Belarus? Yes, but look at the angel carrying an upside-down candelabra. It looks like he's about to burn down the shtetl. Chagall was well aware that the Jews were in danger, that some had already been evicted from their homes and that his own paintings had been shown at the Degenerate Art exhibition in Germany.

On the eve of the Second World War, it was important for Chagall to claim his Jewish roots. On the right, the tree rising high into the sky is indeed rooted in the shtetl. And the little violinist to the right of the bride recalls the traditional music of itinerant Jews.

But Chagall had been living in Paris for several years and, in 1937, he became a French citizen. The blue Eiffel Tower standing behind the bride and groom is a symbol of this new identity.

This identity, however, does not replace the first, but rather is superimposed on it. This is undoubtedly the significance of the giant rooster behind the bride and groom. The animal is the symbol of France, born of a Latin pun, "gallus" meaning both rooster and Gaul. But the animal may also refer to the rite of Kapparot: this ritual of atonement practiced by some Jews on the eve of Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, consists of spinning a live chicken over one's head. The animal is then killed and donated to charity. For the Jews, the rooster is able to distinguish between night and day, since it announces the day, and is able to differentiate between Good and Evil. On canvas, its enormous eye gives it the power to read the dark future ahead.

Autobiographical, the painting is also revealing of the many artistic influences in his work: surrealism with the goat-cello above the bride and groom, Delaunay's colors and shapes for the sun and the Eiffel Tower. Animals and musicians are elements often found in Chagall's paintings.

In 1941, Chagall fled France to escape a roundup. The couple fled to the United States, but Bella died three years later...