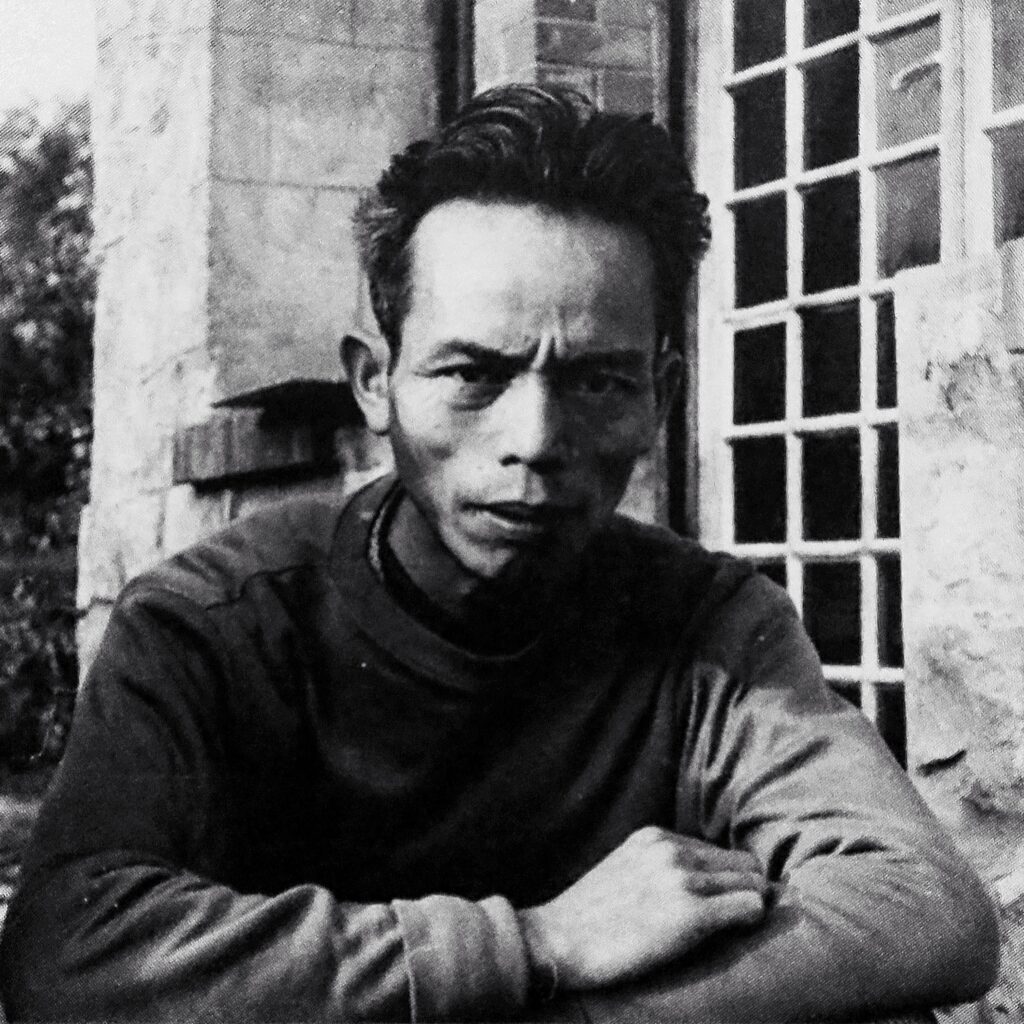

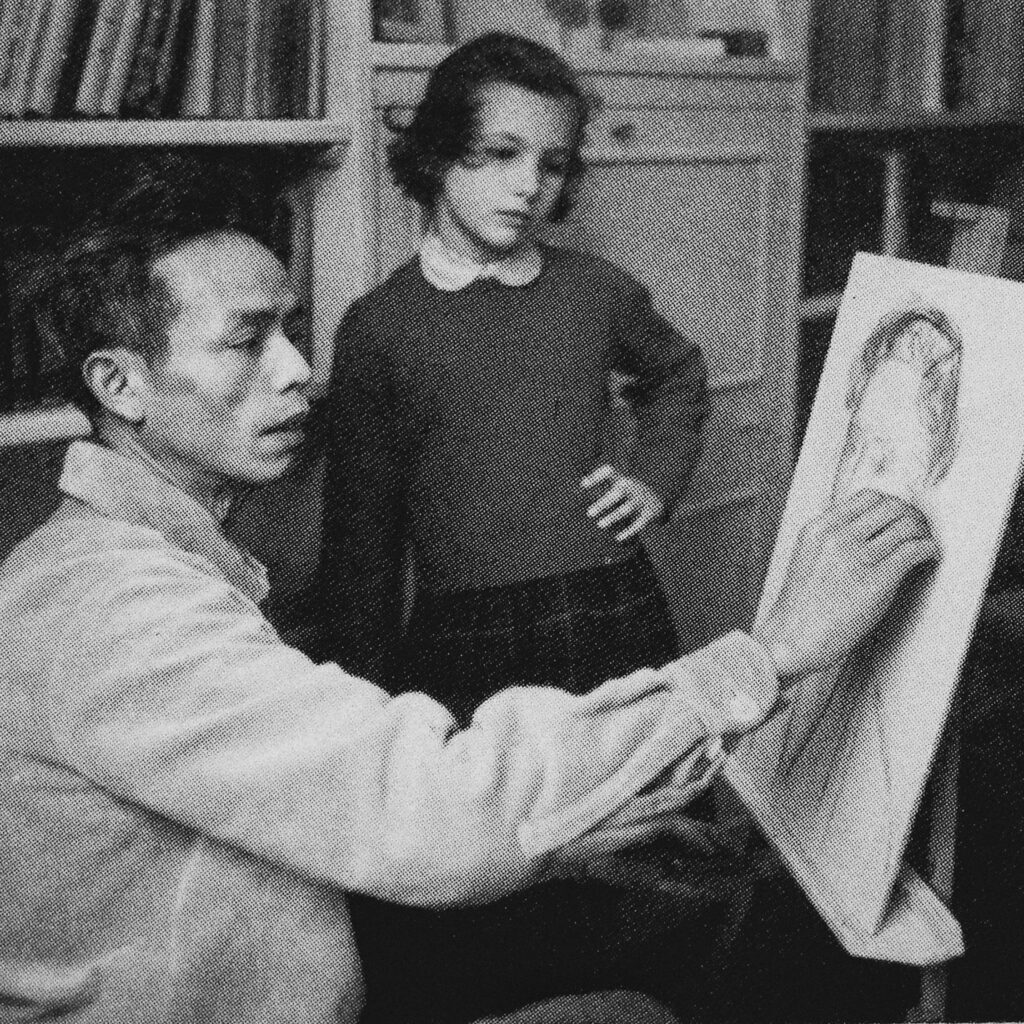

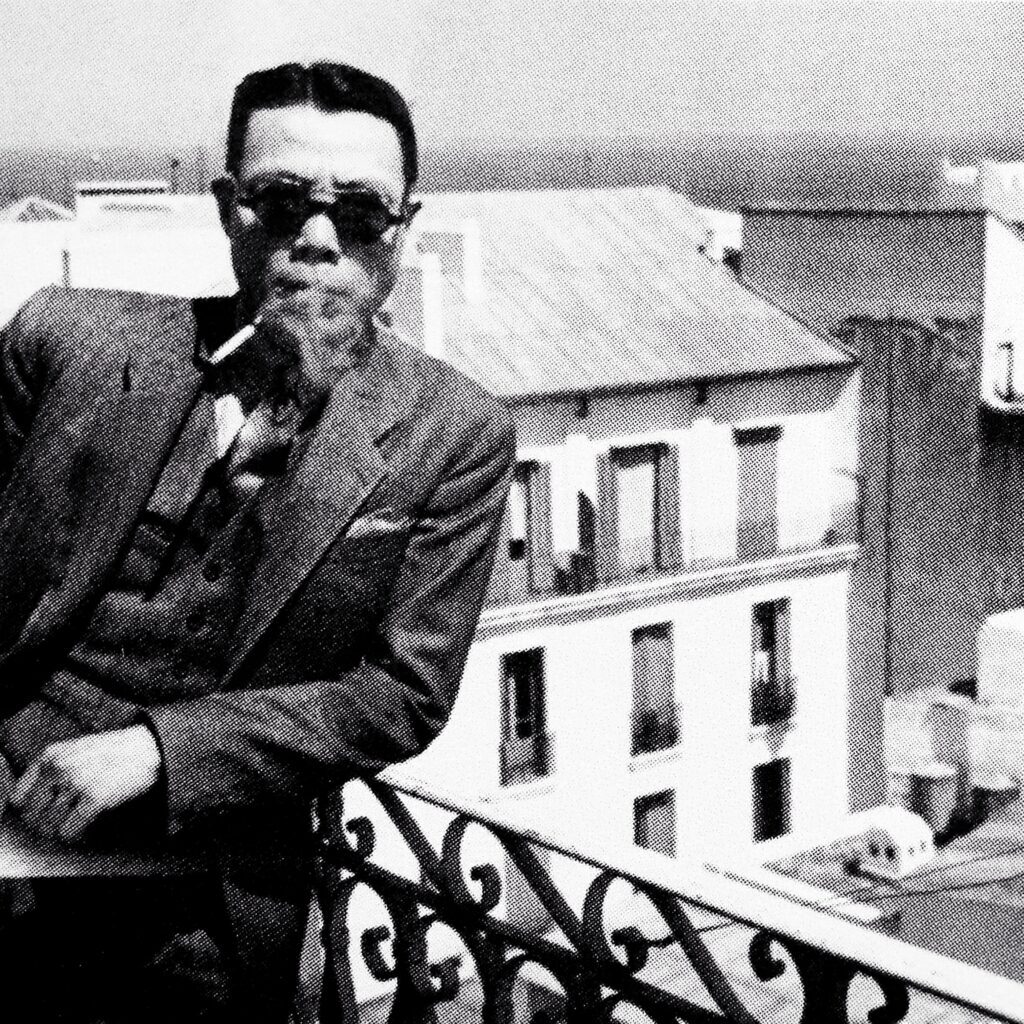

Nguyen Phan Chanh (Vietnam, 1892-1984)

La Marche Nuptiale

signed and dated 1937 (lower right); signed in Chinese with a seal of the artist (lower left)

ink and gouache on silk

48.5 x 85.5 cm. (19 x 3 3/4 in.)

painted in 1937

on seal of the artist

LA MARCHE NUPTIALE OR WEARINESS IN STEP

This gouache and ink on silk, large dimension (48,5 X 85,5 cm) is of particular importance in the work of the painter.

In 1937, Nguyen Phan Chanh painted for the first time a group moving (even though out of eleven people, four were children and five remain motionless spectators). This group moves from right to left (looking at the work) while the woman carrying the child and the three young spectators watch the procession. This group moving is a change from the painter’s previous works depicting primarily individuals, alone or very few, almost still, often seated, that we already analyzed: La Marchande de Oc (1929), Les Couturières (1930 ), La Vendeuse de Bétel (1931), Les Cases Gagnantes (1931), L’enfant à l’Oiseau (1931), La Jeune Fille au Perroquet (1933). Even La Femme dans la Rizière, almost contemporary (1936), feels frozen. In these previous works, all gestures in the upper body are supple, airy and precise. Each one is engaged in a traditional activity: petty trade, sewing, playing, cooking, eating and listening to the bird in the cage. In almost all of them, the model is seated and only the upper limbs appear in movement.

In "La marche nuptiale", the upper limbs are almost hidden, and the lower limbs no longer exist. Only the movement of the group counts. The allusion to a traditional theme (the wedding march) is obvious: we note that in addition to the traditional holder of offerings to the family of the groom, the two chaperones surround the bride.

This theme of the group moving contrasts with the artist’s previous static representations. Why is it a group walking instead of static individuals? A walk, yes, but a real dynamism, no.

Let’s look at the faces: the bride’s is the most expressive one of all. The expressiveness of the face is unusual for the artist who usually favors quasi-interchangeable faces. The young woman’s face shows, to say the least, a certain weariness. It is not the solemnity expected in these moments. No, she poses a distant and even weary look on the diaphanous child, in the arms of his mother, herself painted in a clear gouache. As if the idea of maternity weighed as much on the painter as on the bride.

In traditional Vietnam, marriage is an alliance between two families, the result of discussions via matchmakers. The family’s interest prevails over the love of the future couple. Passion is not tolerated in this situation meaning that the Kim-Vân-Kieu, where passion and social constraints are in fierce competition, appear as revolutionary in the traditional Vietnamese mentality.

This is perhaps the key to understand Nguyen Phan Chanh: he ennobles the past, knowing that it can’t last.

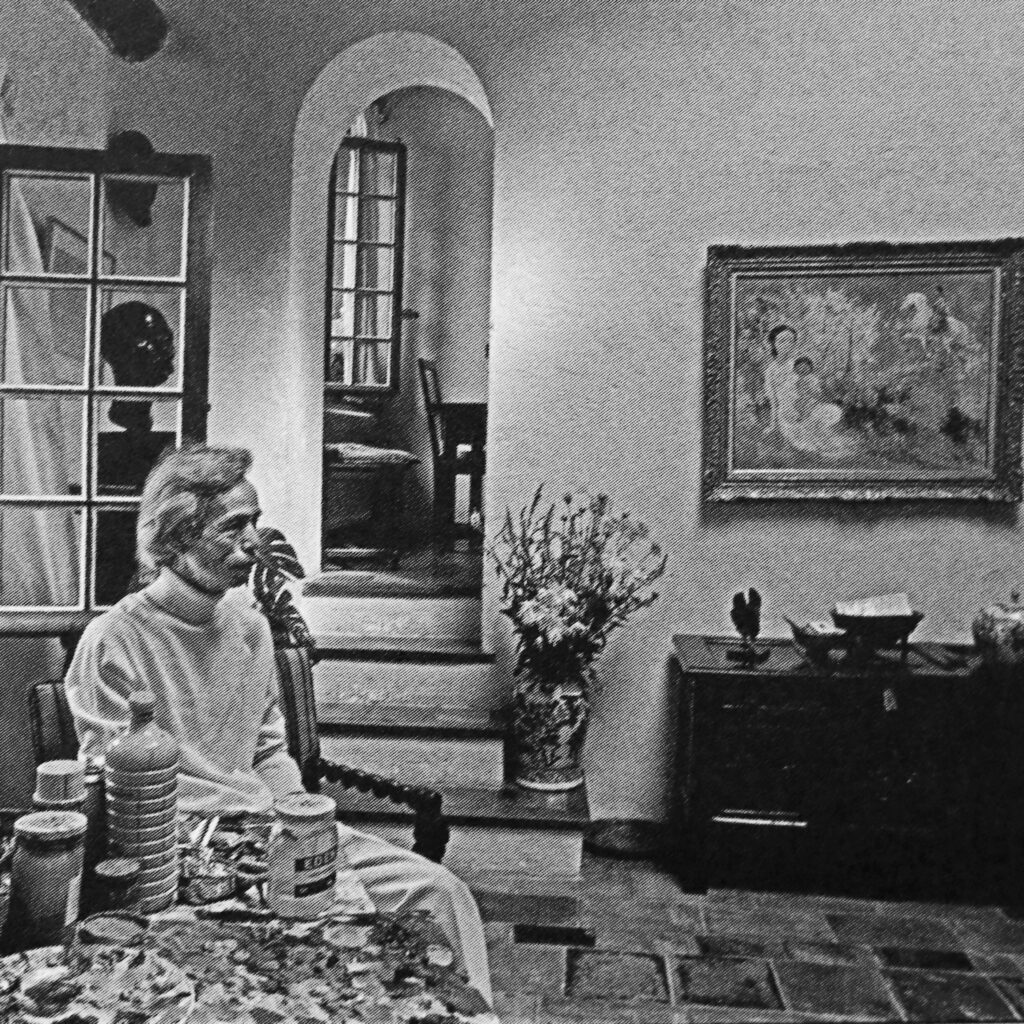

Nguyen Phan Chanh chose not to go to the West, unlike some of his fellow students, such as Vu Cao Dam, Le Pho and Mai Thu (among others). Nor was he a revolutionary (neither nationalist nor communist) as his later career will show, and with time he will no longer believe in the traditional world he dedicated his life to. The calligraphy that usually compliments his work is not even there, as if words have become useless.

Why not?

Because 1937 is a special year.

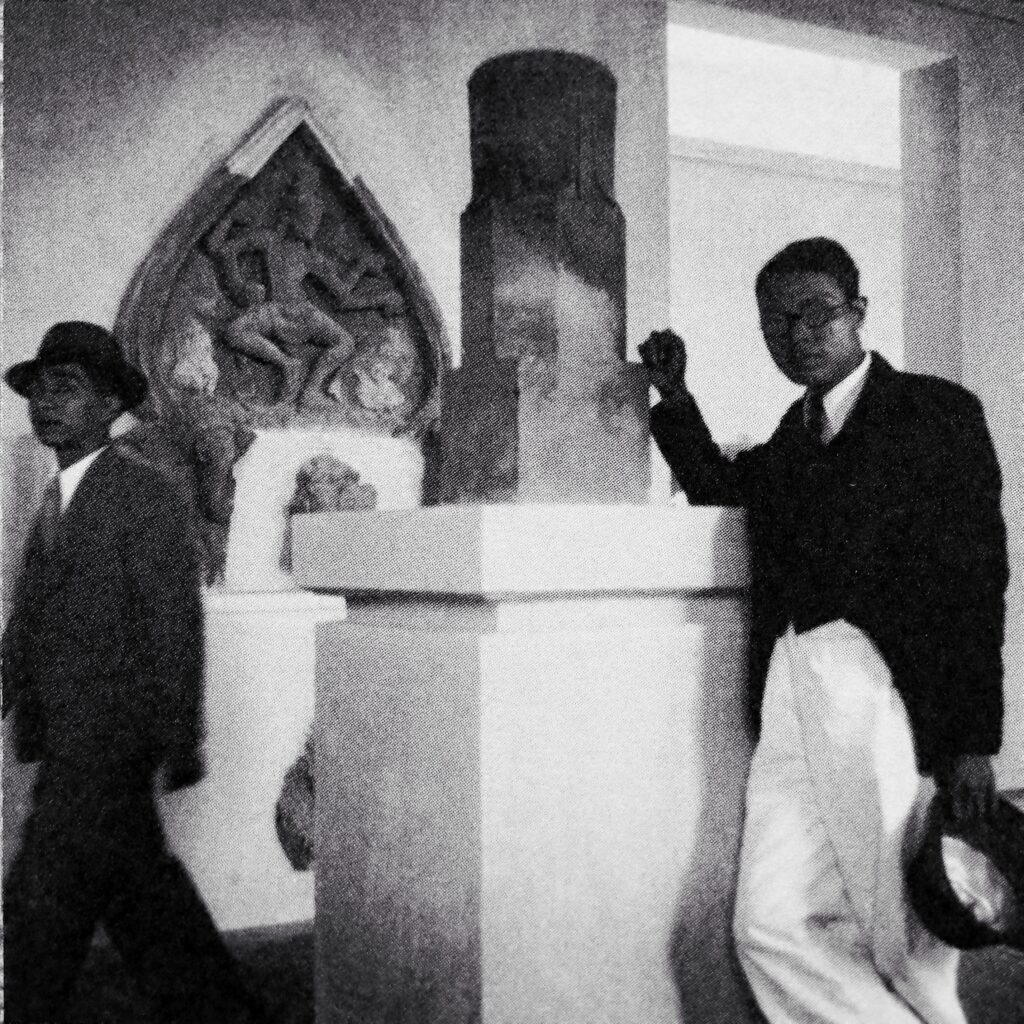

The Colonial Exhibition of Paris (1931) was a celebration of his talent followed by successful exhibitions: his first personal one in 1933 in the Hanoi Bank building, in 1935 and 1936 – the first two exhibitions of the SADEI (Société annamite d’encouragement à l’art et à l’industrie) in Hanoi – and in 1938, for a third one.

But two major historical events changed the course of the artist’s life:

First, in 1936: in June, the "Front populaire" won the elections in France and the Vietnamese progressives, Nguyen Phan Chanh was a member, called for a transfer of French social and political advances to Vietnam. The French government proclaimed a broad amnesty (on August 27) which freed many of the revolutionary executives and all of Vietnam was celebrating. The different factions – nationalist, socialist, communist – proposed their solutions of progress. Long workers’ strikes (374 from June 36 to August 37) disrupted all production in all sectors, and the Vietnamese people were willing to drastically take charge of their lives, especially Nguyen Phan Chanh.

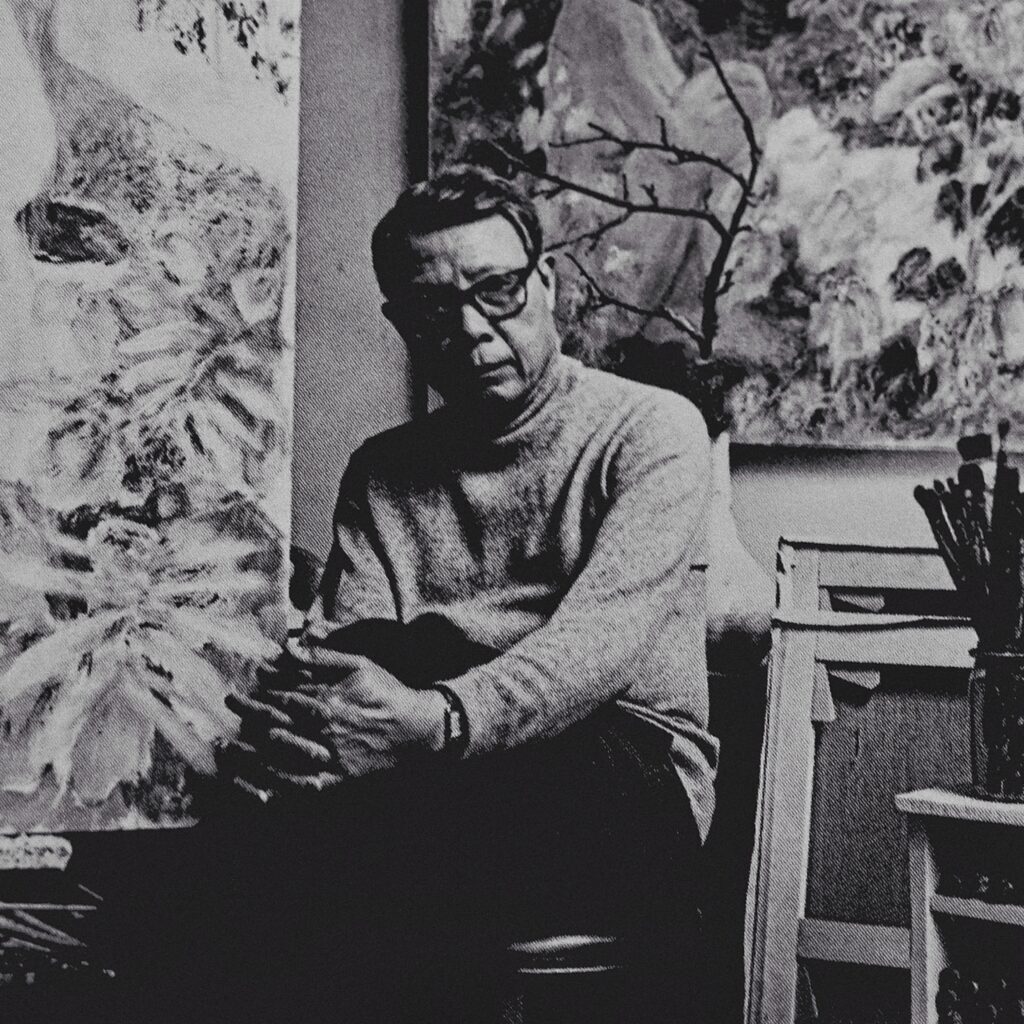

Second, in 1937: Victor Tardieu, head of the Hanoi Fine Arts School, died and his successor, Evariste Jonchère – following the ideology in power in France (summarized in Justin Godart’s “Rapport de Mission en Indochine” (January 1-March 14, 1937) – decided to make the School an institution that would no longer teach artists, but would train artisans. The idea at that time, more retrograde than modernist, met the opposition of a good number of artists already trained like Nguyen Phan Chanh. He was vehemently opposed to Jonchère and as a consequence was not allowed access to any event at the École des Beaux-Arts or to any patronage. The painter, from then on, exhibited alone and without official recommendation. After the great success of his 1938 exhibition, he decided to return to his native province of Ha Tinh.

Let’s not be mistaken, it was a bruised man painting this work. Prescient, he knew that the future could not be bright as long as the past was annihilated. He seemed to fade away in front of History as if its meaning – wether claimed or suffered – did not work for him any longer:

His signature in Romanized letters and if the date is clearly visible it is not as strong in the calligraphy. His stamp (“Hong Nam”, “Hong”: large/wide, “Nam”: South) at the bottom left seems to fade into the conical hat and partly masked (the only case found in the whole work) by the man’s panel. At the top right the signature in Chinese (“Hong Nam” again) seems almost subdued.

He modified his usual chromatic tones; the chiaroscuro claimed in the previous works is not as dark and mixed with a discreet coloration (the bluish color that falls from the woman’s conical hat with her head bent forward). The process had already been used – but very rarely – in some of his previous works, including “La Jeune Fille au Perroquet“, 1933, before Nguyen Phan Chanh returned to his characteristic brown and maroon cameos.

In this year 1937, Le Pho and Mai Thu participated in the Universal Exhibition in Paris. They joined Vu Cao Dam, who lived there since 1931, while Nguyen Phan Chanh remained in the country. Until his death in Hanoi on November 22, 1984, his painting would only decline.

He, the originally brilliant artist, would only suffer. Like this ceremonial group, he will walk.

To keep walking forward and forever, such is the quest of the artist. But, from 1937, his steps are the steps of a disappointed man.

Jean-François Hubert

Senior Expert, Vietnamese Art