After graduating from the Hanoi School of Fine Arts in 1941, Hoang Tich Chu started a lacquer workshop with his fellow student (who graduated the same year) and friend Nguyen Tien Chung, on Hàng Khoai Street in Hanoi. Amateurs were offered views of Hanoi (Hoan Kiem, Tay Ho...) as well as places nearby such as the Master Tay's Pagoda, Bac Ninh, and further away, Halong Bay, the Middle Region and a large lacquer for one of Hué’s churches.

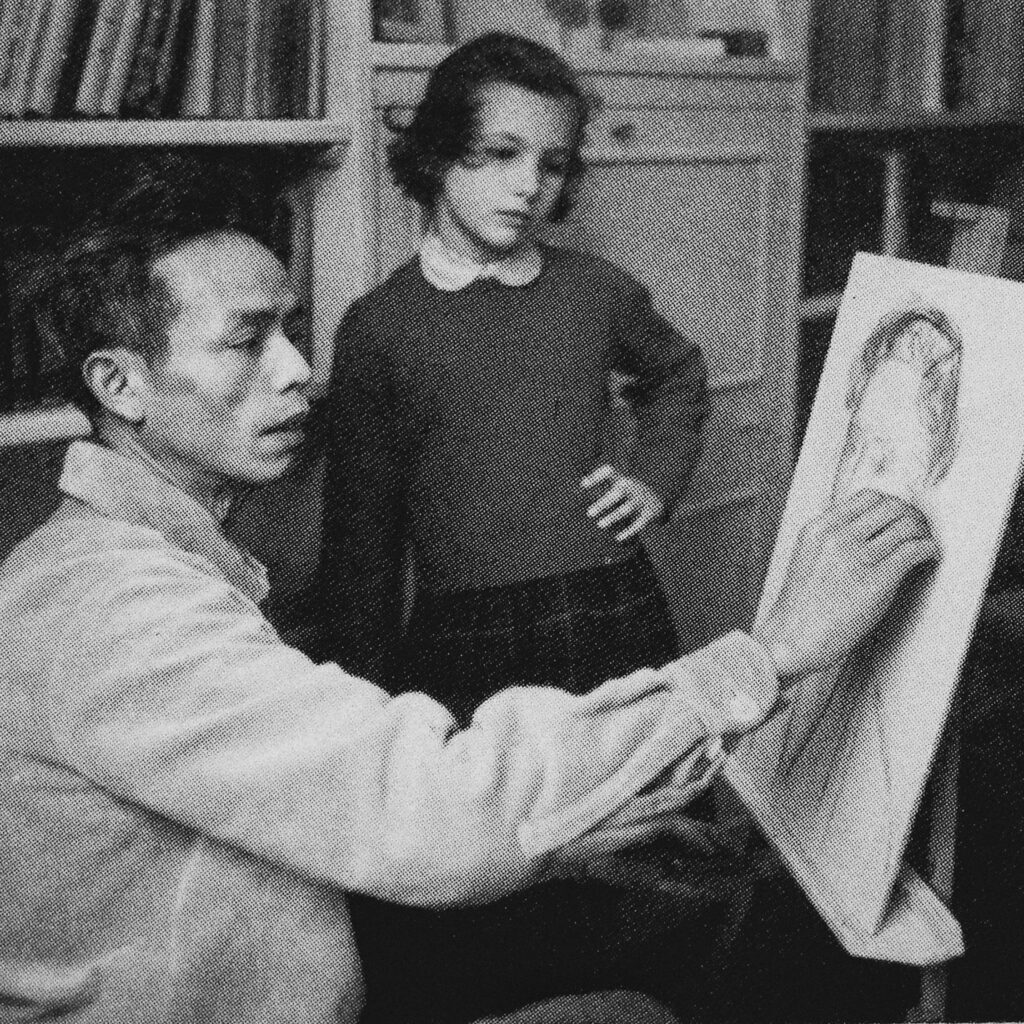

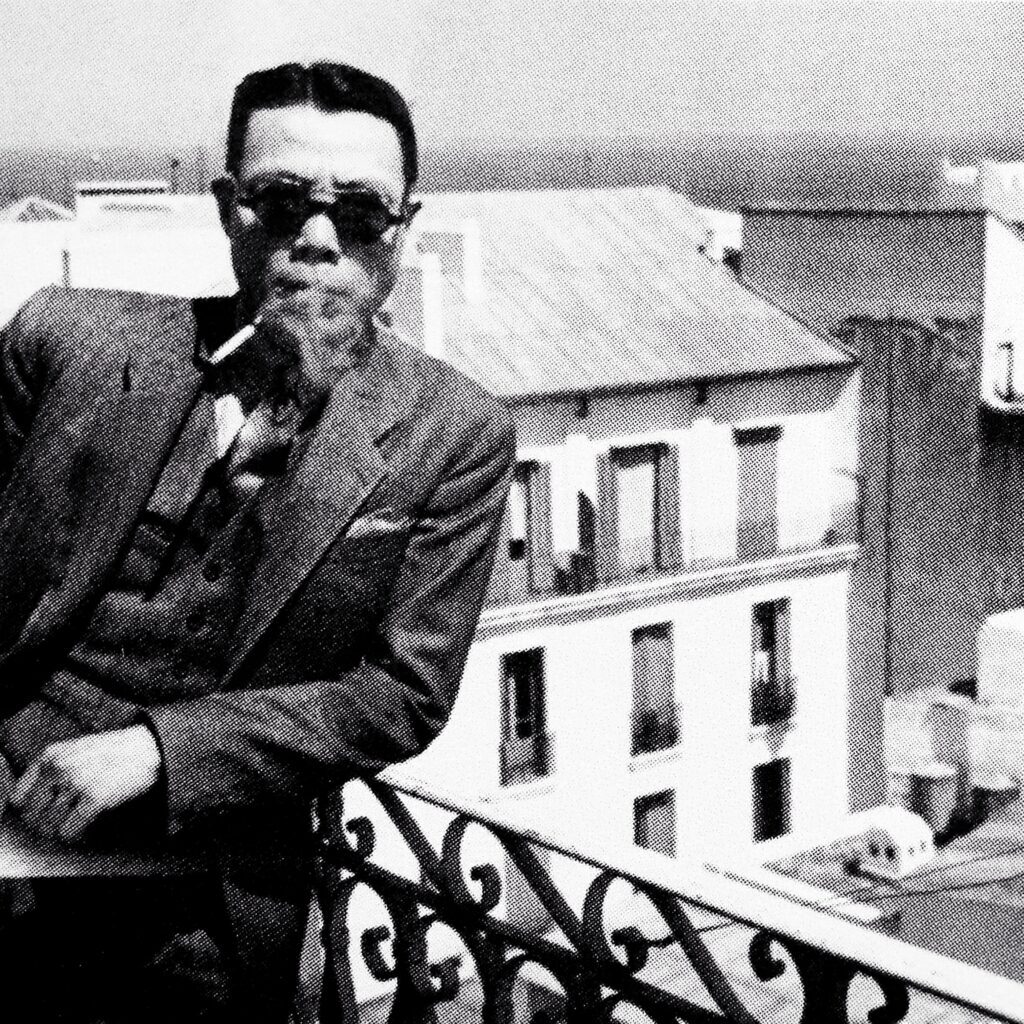

In the 1940s, Hoang Tich Chu defined his own code of conduct for his works: their conception, execution and development would all be done only by himself. This was very different from other artists like Pham Hau who would often repeat the same theme, which enabled him to hire a large number of assistants, as did Nguyen Gia Tri later on. Hoang Tich Chu however did not repeat his subjects and did not delegate the execution of his works to anyone else.

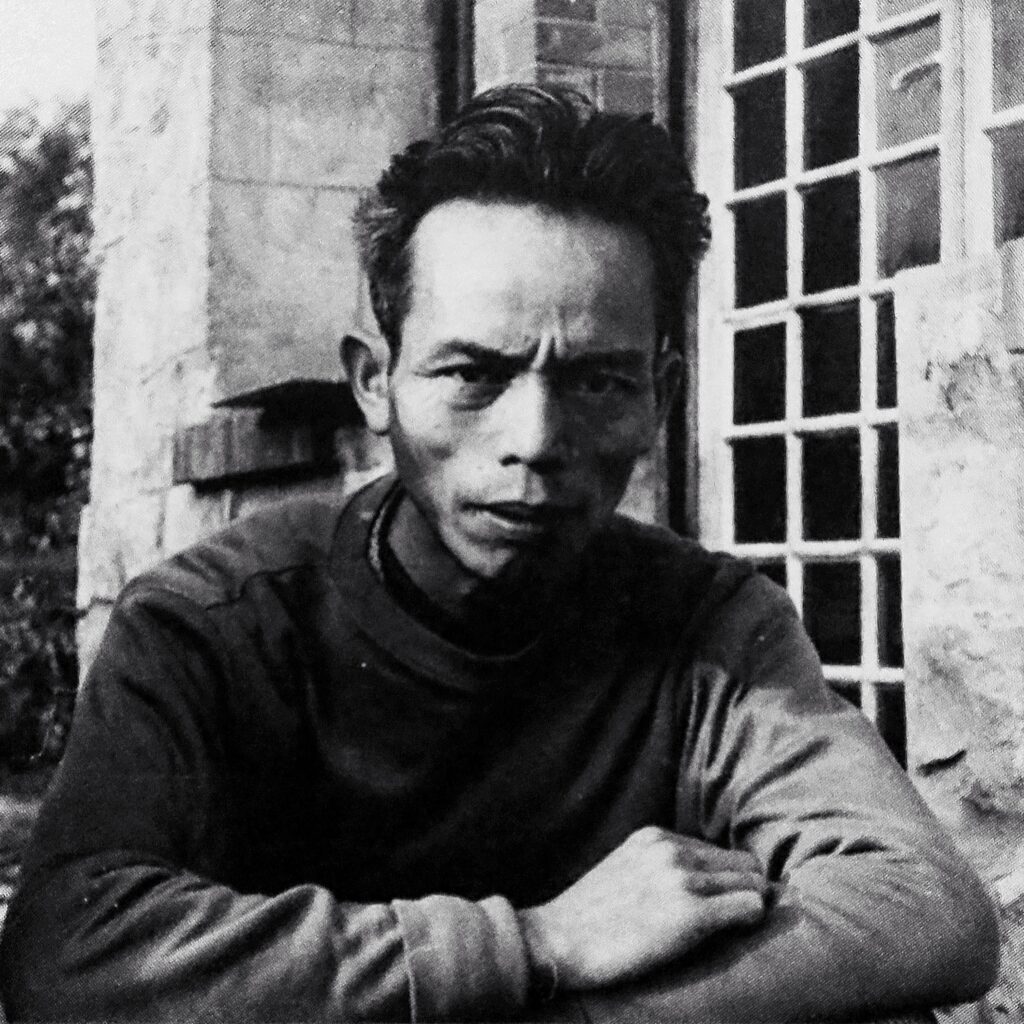

Hoang Tich Chu closed his Hanoi studio in 1946 and joined the Vietminh in their struggle for independence in the Bac Ninh region, an area he knew well as a native of Tu Son. He left the maquis in 1947 to return to Hanoi. The maturity acquired over these two years brought about a change in his style: his line became looser and his palette more colourful. In Dong Ky, where he spent a lot of time, he observed the techniques of experienced woodworkers and their related techniques such as mother-of pearl work. He also met the buffalo and cow breeders who have the ancestral habit of buying their livestock in Lang Son and, even further, in Cao Bang, before selling it in the Delta.

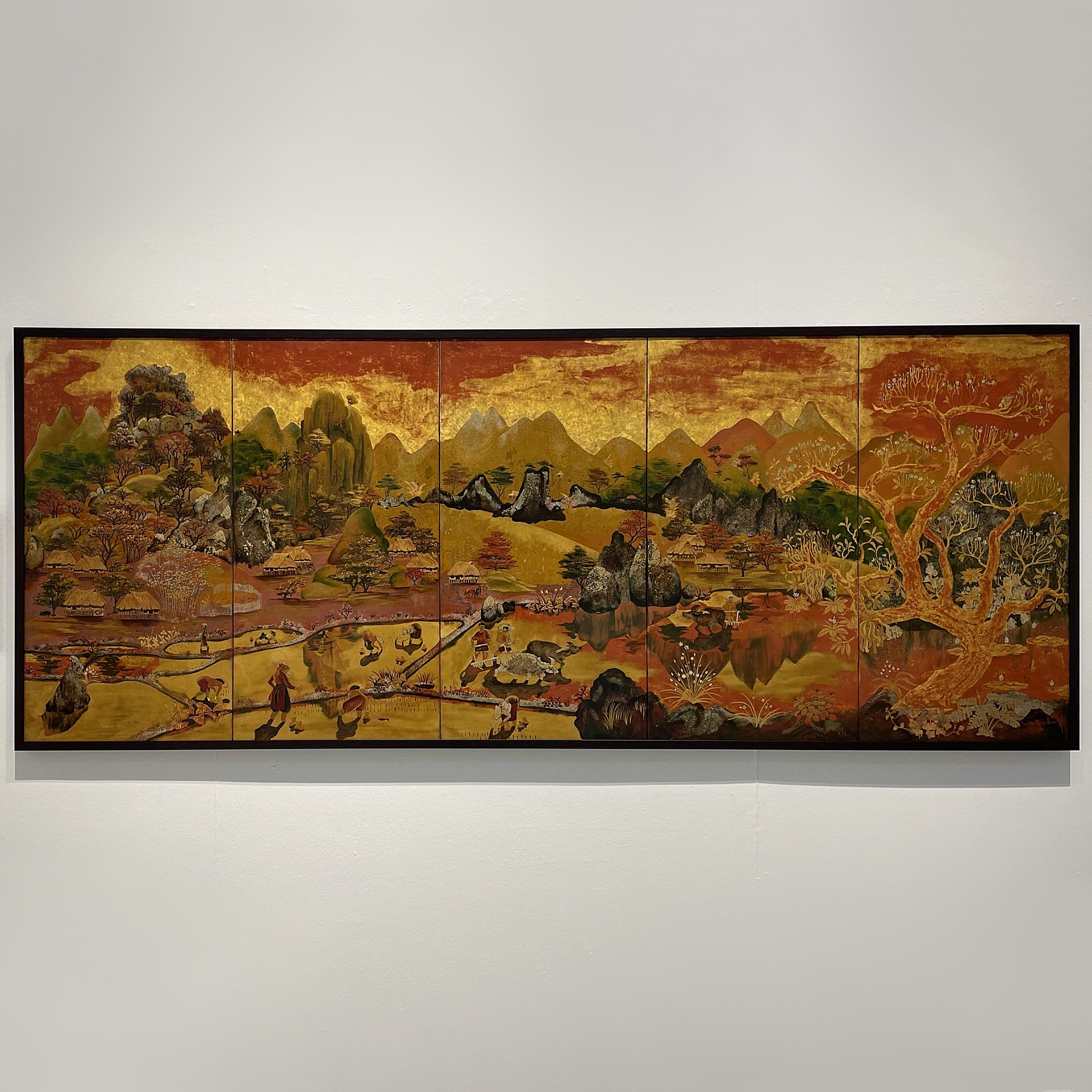

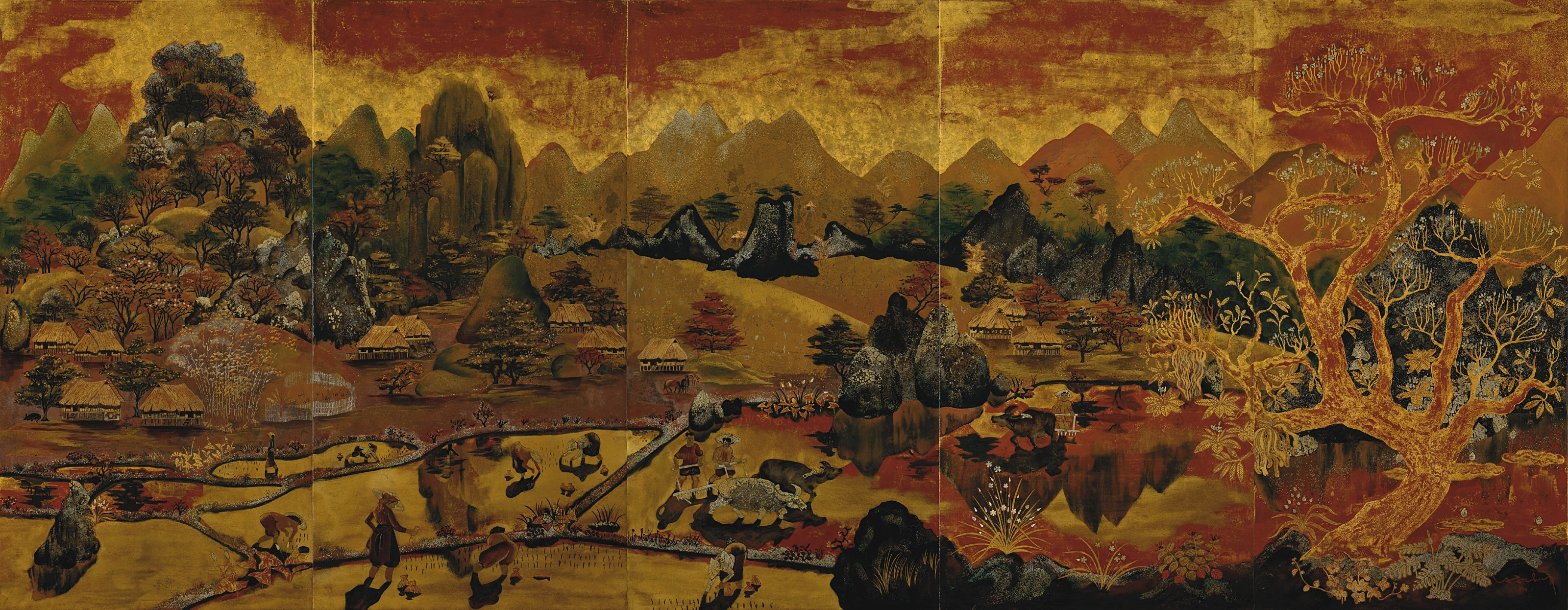

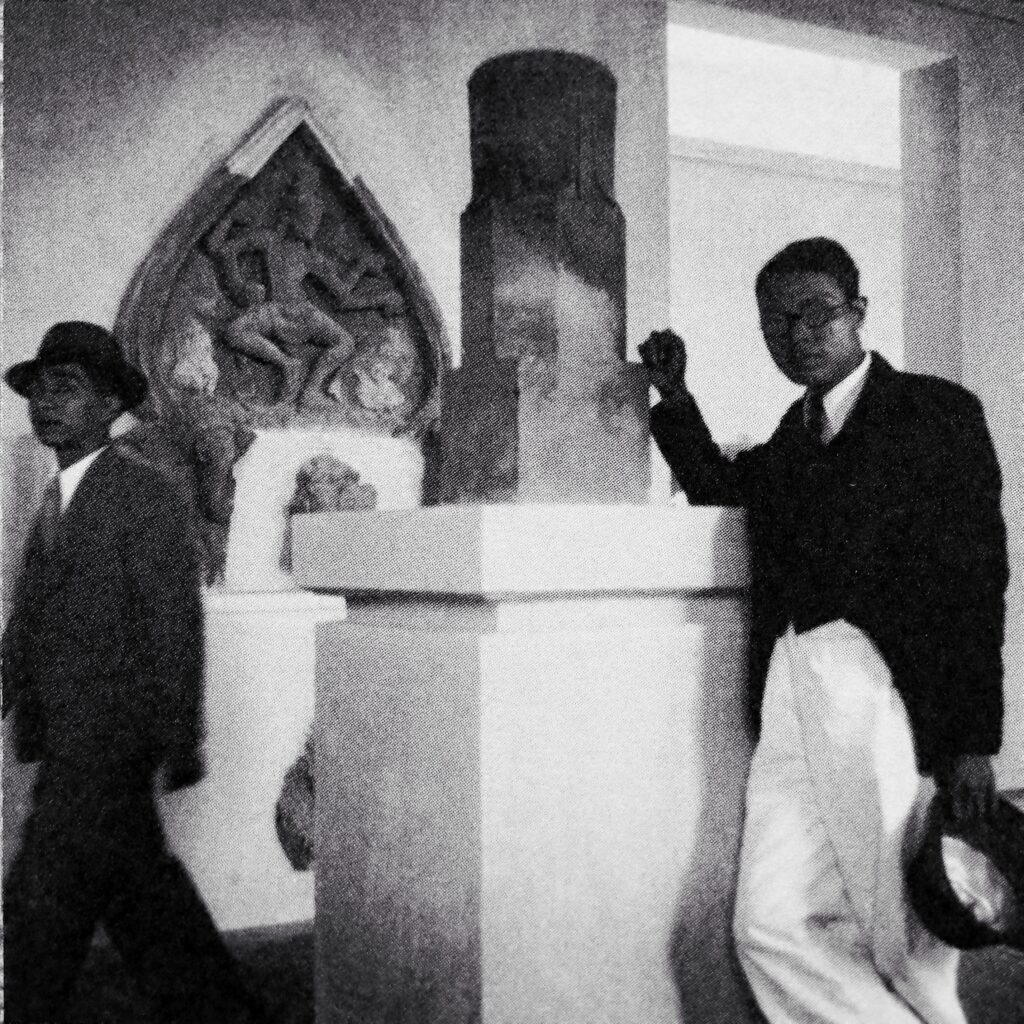

On their recommendation, he went there at the end of 1948 and returned to Hanoi for Têt in 1949, after a three-month stay. This is when he produced this large work (225 cm), composed in 5 panels, each of them constituting almost a whole independent view of one another while at the same time conveying a majestic feeling when combined.

The painter offers us an inhabited landscape of the Upper Region, an area he previously refused to locate to. The landscape is filled with a profusion of sugar loaf trees, rice terraces and houses on stilts. Small Hmong horses are also seen, one brown, the other white. There is also the images of buffaloes and farmers transplanting rice, guiding the buffaloes pulling the plow. It is the observation of a man who is a champion of naturalism, yet elevates this to a phantasmagorical naturalism. Everything is true and captured, but above all, everything is felt, thus revealing the artist’s poetry.

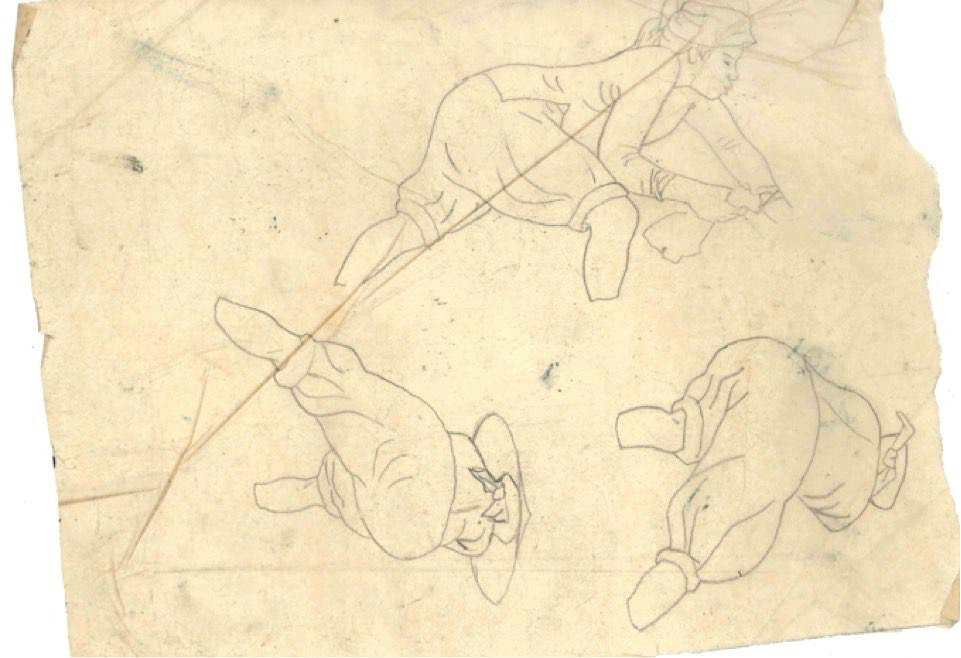

The work is accompanied by a preparatory drawing executed on site late 1948 and 3 fragments of tracing (1:1 scale) probably executed in Hanoi in 1949. They give us information on the painter's technique: drawing on the motif, then tracing in the studio and then executing the lacquer itself. These drawings serve also reveal the excellent draughtsmanship of the artist.

Hoang Tich Chu loves colour: yellow, red, white, black, green, silver and gold, explode forth in his work. Abundance however, is nothing without subtlety: fine differences in tones, the choice between solid and powder, the subtle use of eggshells, all contribute to the quality of the work. For example, the painter uses the convexity and concavity of the shell fragments. After applying a layer of lacquer, the convexes appear white and the concaves darker. This allows the painter to create yet more masterly effects.

His mother Hoang Tuyet Trinh, a jeweller, had a direct influence on Hoang Tich Chu by encouraging him to use gold as powder. This is used effusively to depict the water in the rice fields, or in leaf form, to depict the sky above the mountains. Water and air, the principles of life, are thus magnified by gold.

Hoang Tich also uses silver powder, especially in the depiction of bushes. He also used a double effect of tone on tone but also of eggshell and lacquer as seen in one of the buffaloes, for example. Note also the numerous shadow effects - the mountains, the people and the buffaloes reflection in the water of the rice fields - and the numerous incisions which, for example, highlight the brown trunk and branches in the trees or, elsewhere, the golden leaves.

The work presented here, majestic and subtle, is a true masterpiece and testifies to the artistic fervour and perfect technique of a painter at his peak.

Jean-François Hubert,

Senior Expert, Vietnamese Art