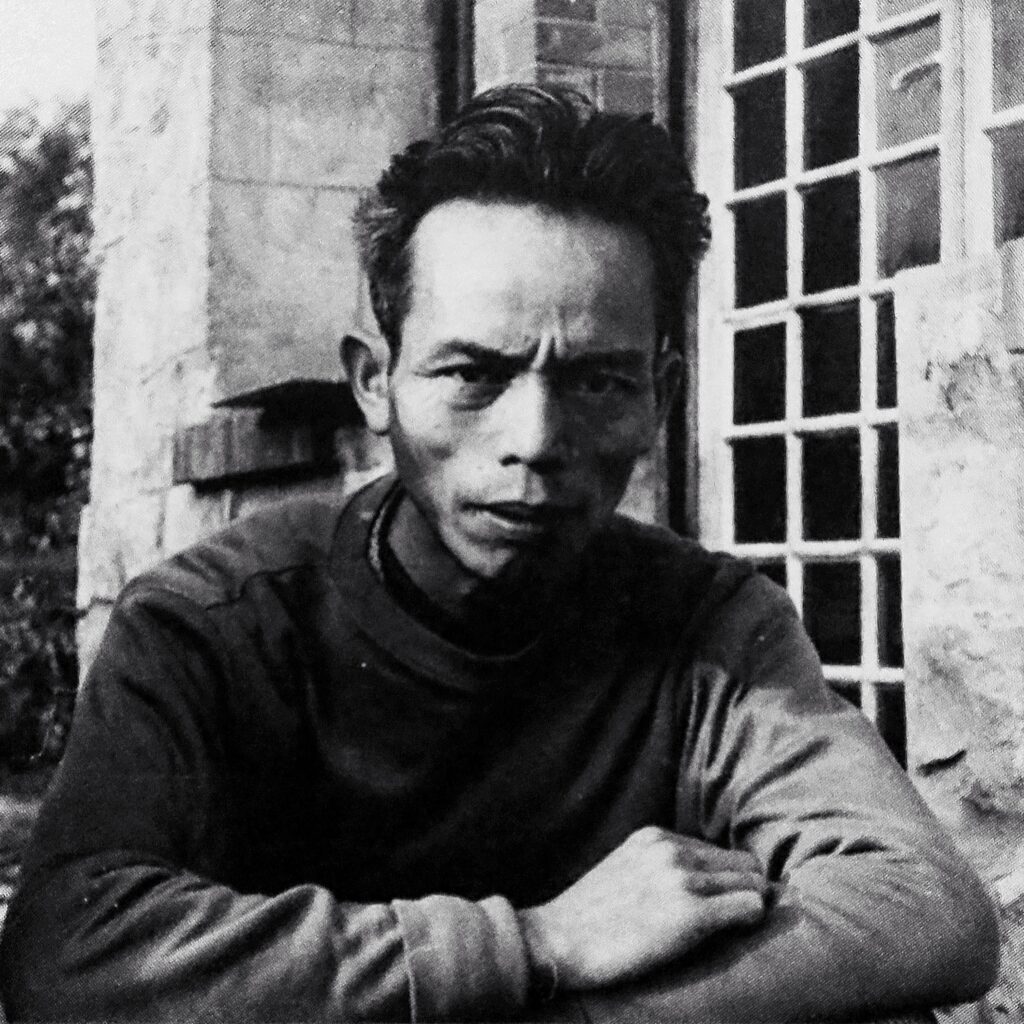

Le Van De (Vietnam, 1906–1966)

A Lady of Hue

signed in Chinese and signed, inscribed, and dated 'Le Van De/Hanoi 45' (lower right)

ink and gouache on silk

80 x 34 cm. (31 1/2 x 13 3/8 in.)

Painted in 1945

one seal of the artist

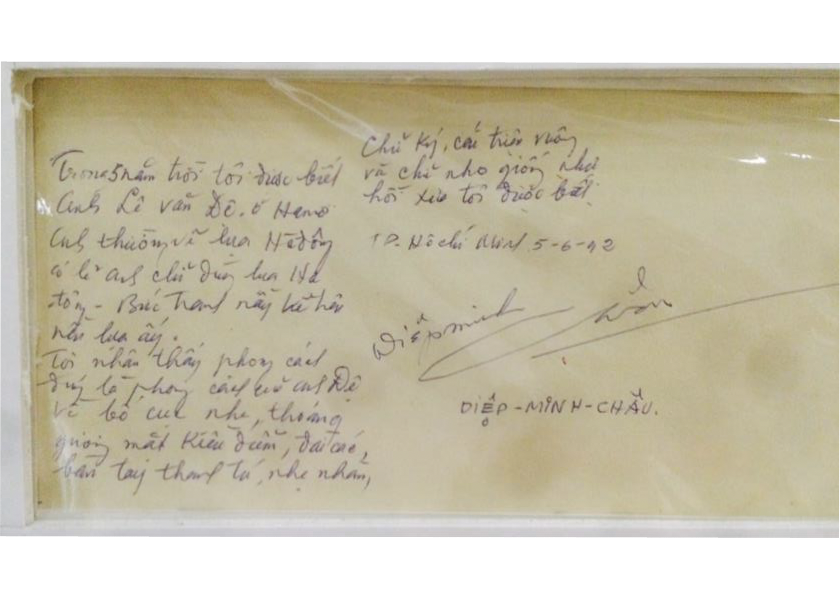

This artwork is accompanied by a letter of authenticity dated 1992, signed by Diep Minh Chau.

The quest for authentification in Vietnamese paintings.

Example from Le Van De – Lady of Hue

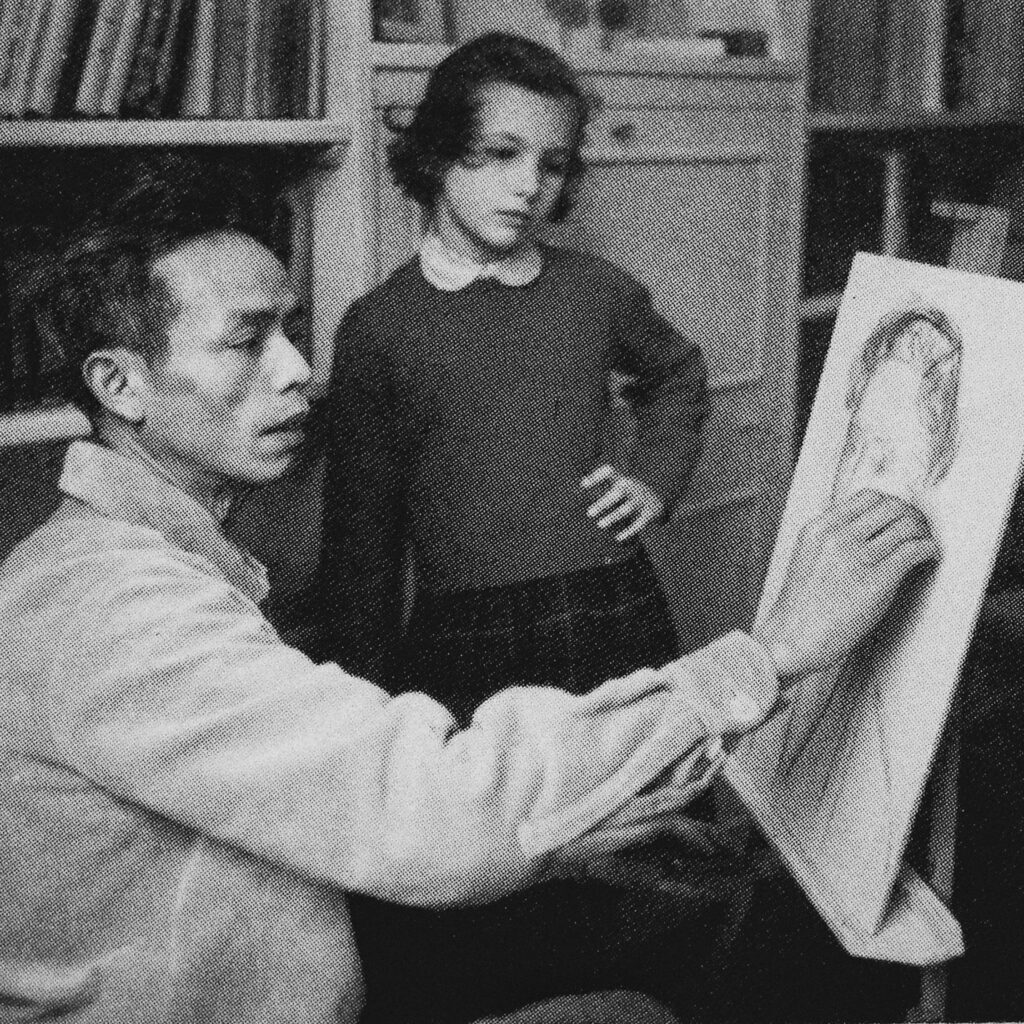

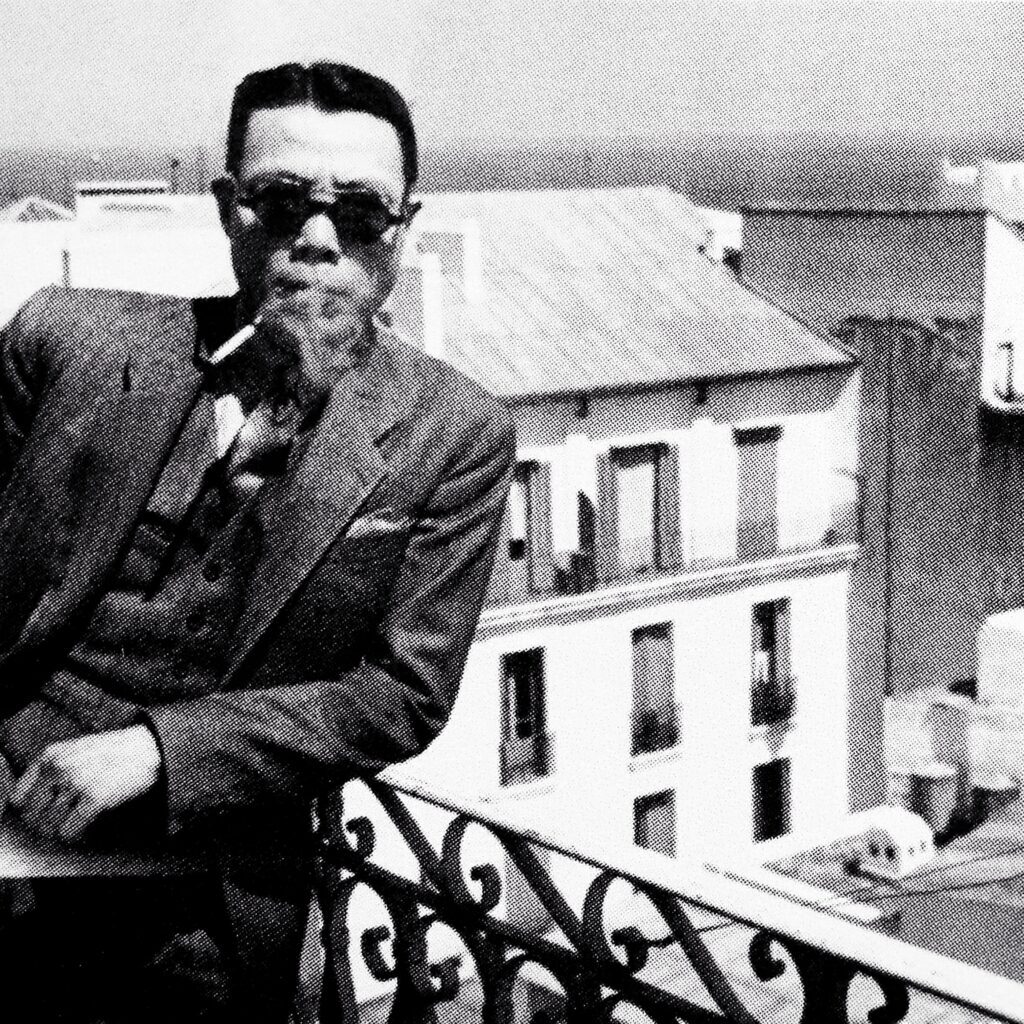

Le Van De is a painter born in Ben Tre, south of Saigon. A significant detail considering that most recognized Vietnamese painters who attended the Hanoi Fine Art School are natives from the North. Just after graduating in the first tier of students (1925-1930), Le Van De goes to Paris to pursue further studies in 1931 in the City’s School of Fine Arts. As he is from the South he is also a devout Catholic who, very early, showed a particular interest in Rome, the world centre of Catholicism.

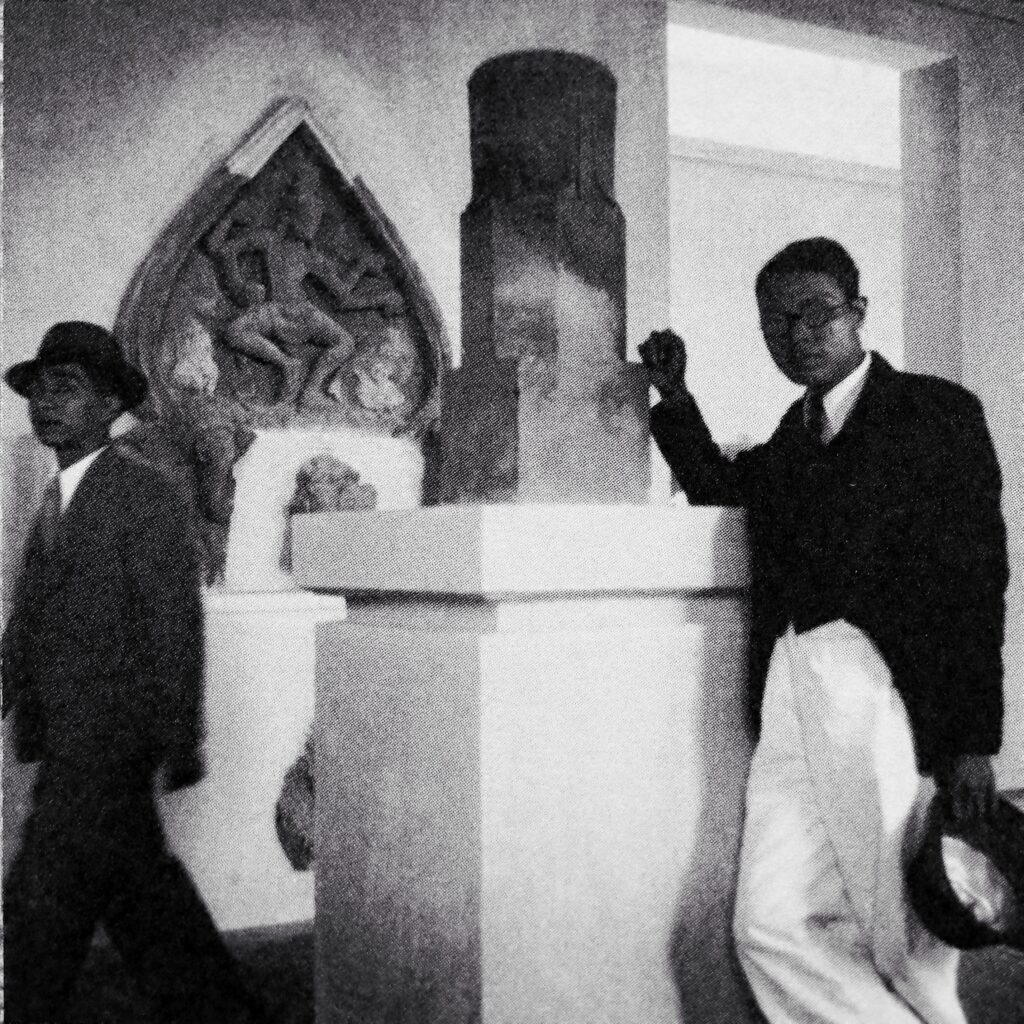

In 1936, he is awarded the first prize of the exhibition “World Catholic Press Exhibition” in Rome and is also invited to decorate the interior of the Vatican.

In 1939, he returns to Vietnam but will keep spending time in France. In 1945-1946, he is caught in the civil war in Hanoi. After the partition of Vietnam in 1954 between the communist North and the nationalist South, he emigrates to the South – as did 800 000 Catholic followers – where he becomes Director of the “Saigon Fine Art College “. He dies in Saigon in 1966 without setting foot once in the new communist North which he disliked intensely.

The painting reflects the master’s work at his best: the beautiful woman incarnates Hue, the imperial city, with her great elegance dressed in her traditional clothing. This is a true expression of Le Van De’s attraction for tradition and distinction. Through his work he depicts wholly the lifestyle which prevailed in ancestral Vietnam showing mastery in his use of gouache and ink on silk lay down on paper. The softness in his brushstroke, the use of subtle tones characterizes perfectly his post-war production. At the lower right, a very beautiful calligraphy in Romanised letters and Chinese characters (or Sino – Vietnamese) indicates the date and the place of the work: Hanoi 1945.

To keep the focus on the elegant lady, the background is un-intrusive with its light pencil strokes giving a sense of place without overloading the composition. Even the curtains hanging around the window are barely suggested. The silk is in rather good condition, the colours well conserved and the faded ink of the signature and the lower right notes shows the age of the painting.

The work presented, here, demonstrates every artistic, technical and historic characteristics known to the painter. It is rare to find works in Vietnamese modern painting with such an interesting origin and such a solid authentication.

The authentification

Indeed, up to recent years, due to the wars, the relocations as well as a weak interest in the market for this art, it is difficult and rare track down the provenance for most of the works.

But, this painting shown previously was authenticated by a handwritten letter, dated June 5th, 1992 by Diep Minh Chau.

The translation of this letter is as follows:

I have known Le Van De, who lived in Hanoi for 5 years. He usually painted through the medium of Ha Dong silk.

He probably utilised Ha Dong silk – this painting is executed in this type of material.

I realised it is, in all respects, De’s style; the layout of the work is very soft, the face depicted seems charming and elegant, and the hands are gracefully delicate.

His signature, square stamp, and Chinese inscription remain precisely the same as I used to know.

Signed, dated, and located: Ho Chi Minh 5-6-92, Diep Minh Chau

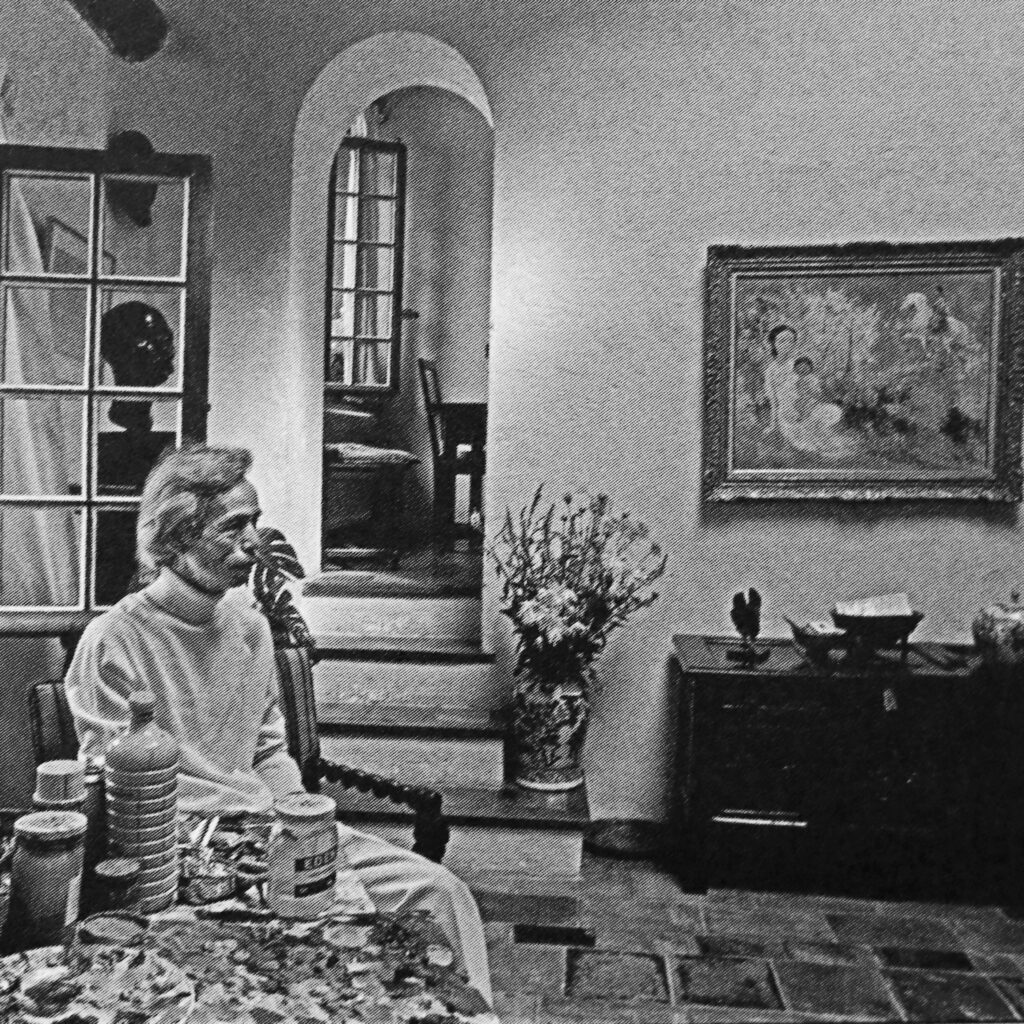

Born in Ben Tre like Le Van De, Diep Minh Chau (Vietnam, 1919-2002) graduated from the Indochina Fine Arts College, was in the 15th batch of students (1940-1945) and also studied at the Prague Fine Arts Academy (1951-1955), and became a lecturer for the Fine Arts College of Hanoi.

Diep Minh Chau enjoys an excellent and indisputable reputation based upon his training, his honesty and his impeccable journey, known as a man who refuses to compromise. And never have any of his papers or his words been ever questioned.

Why the authentification can be such a complicated process?

Since my first visit in 1995, I know that the Hanoi Fine Arts Museum exhibits a fake of this painting. The work is generally extremely weak, the artificial aging is obvious as to the point where it is unsure that the counterfeiter had never seen the original work and chose to mask this with the use of artificial wear and tear techniques. The lower left part is particularly obvious: the counterfeiter avoided copying the writing in the lower right corner by covering it up, indeed the aging ink is a tricky part difficult to hide.

Again, I went personally in May 2016 to the Museum of Hanoi and I can only confirm drastically my opinion: not only is it a forgery, it is also a bad one.

The controversy over the works held by the Hanoi Fine Art Museum is not recent. Some people tried to see this as a consequence of the war: in that sense, Seth Mydans wrote an article on July 31st, 2009, in the New York Times titled A Legacy of War, Fake Art in Vietnam.

The journalist begins his article with this punchy line:

Even the director of the Vietnam Fine Arts Museum here doesn’t know how many of the artworks and artefacts under his care are genuine and how many are extremely skillful copies.

The Director of the Museum, Mr. Binh feigns to see a problem related to the war and a way to assure protection of the paintings against the American bombings:

To replace them on the museum walls, it commissioned copies: some by the original artists, some by the artists’ apprentices, and some by skilled copyists in the museum’s restoration department. They were brilliant reproductions – or variants, as the Vietnamese called those paintings copied by the original artists.

As we can see, the problem is not recent, furthermore, the creation of the Museum in 1965 was the beginning of this authentication crisis.

Le Van De’s work is a perfect example: How can anyone imagine that a Catholic, anti-communist painter, living in the South since 1954 at a time when the border between South and North was totally closed, was able to give some of his works to the Museum?

Can the Museum provide proof of the provenance of the work?

For example, a collector who had Le Van De’s work from 1945 till 1965?

Let’s conclude with M. Diep own words quoted by the Director:

Since the opening of the museum, we have had both originals and copies together,” said Mr. Diep, who has worked at the museum for 28 years. By now, even the staff is not sure which are genuine.

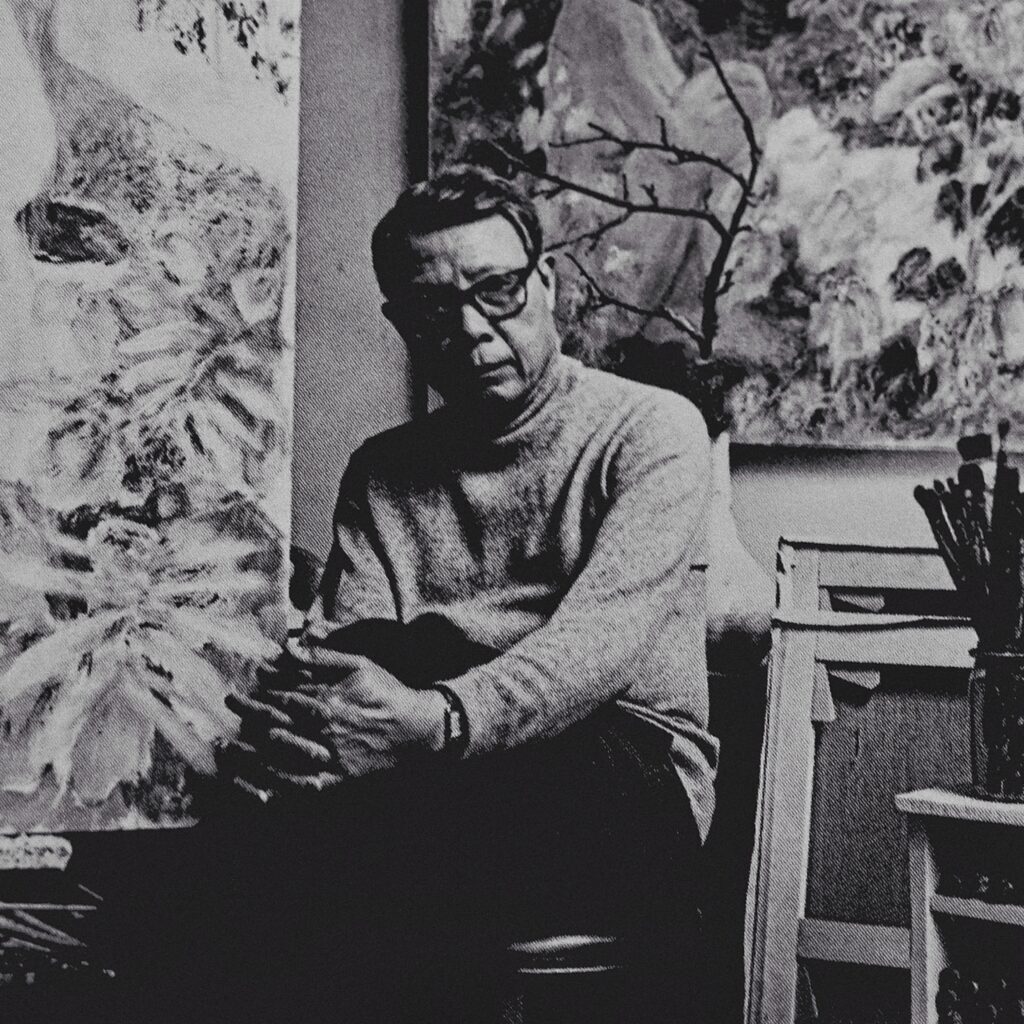

Jean-François Hubert