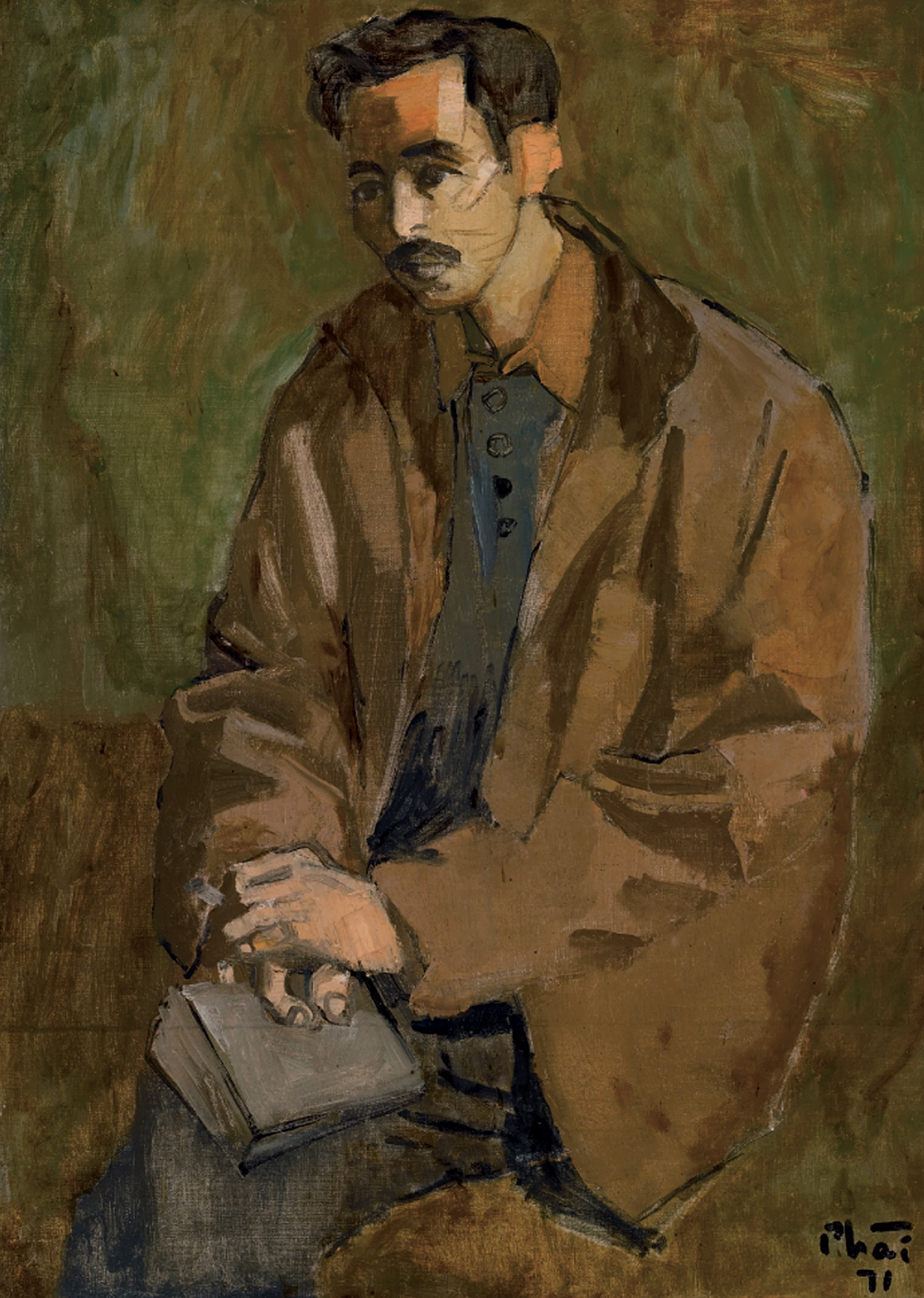

Bui Xuan Phai (Vietnam, 1920-1988)

Portrait De M. Tran Thinh

signed and dated '71 lower right

oil on canvas

78.5 x 56cm. (30¾ x 22¼in.)

painted in 1971

Provenance

Tham Thi Don Thu, widow of the model

Exhibited

1988, Artist's Exhibition, Art and Literature Association of Hanoi, 19 Hang Buon Street.

Bui Xuan Phai, 1971, the « Portrait Of Tran Quy Thinh » or the Tran Dan’s victory over To Huu

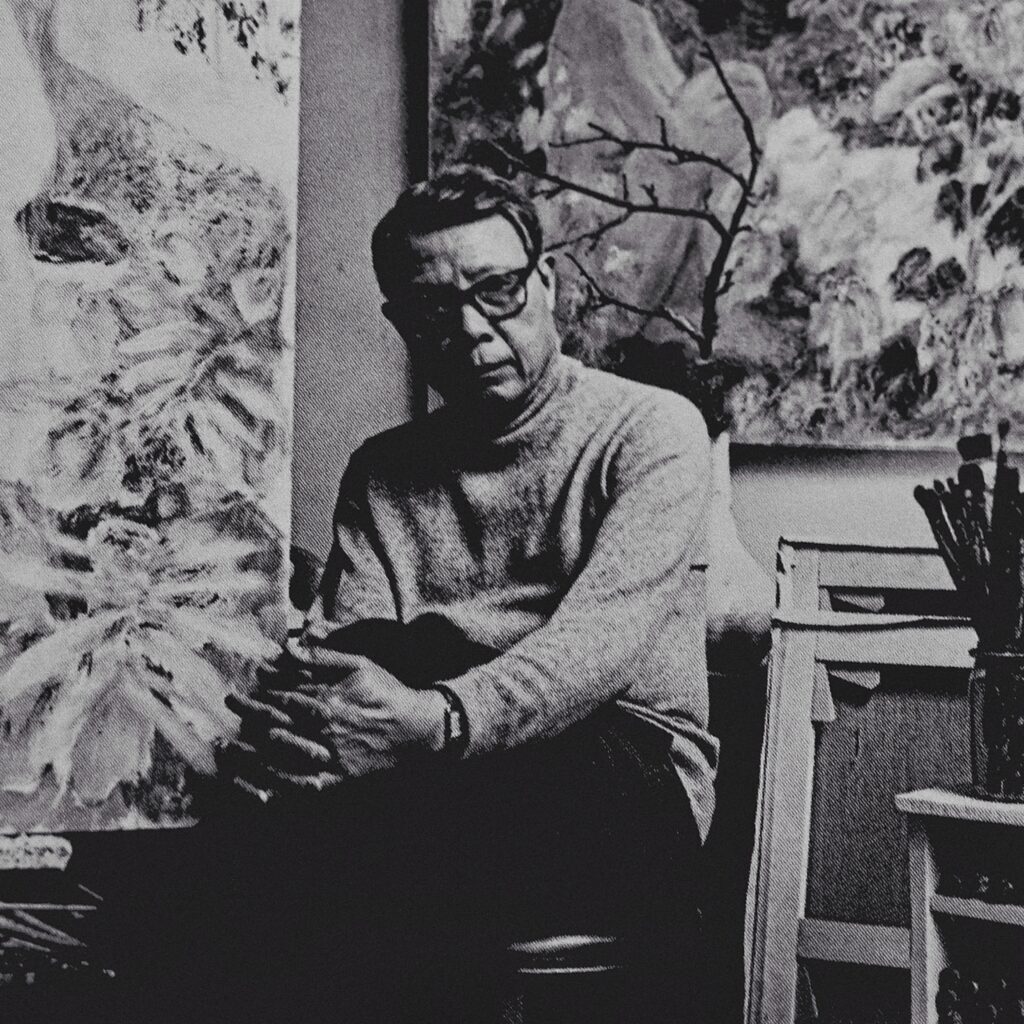

Much has been already written about Bui Xuan Phai (1920-1988). Not the essential, as censorship has been strong there and then.

He was born in Hanoi into a family of scholars.

He succeeded his entrance exam to the Indochina School of Fine Arts (Hanoi) in 1941 in the 15th class with, among others, Nguyen Tu Nghiem. One year after Nguyen Sang and Diep Minh Chau. Bui Xuan Phai could not complete the five years necessary to obtain his diploma, as the School closed after the Japanese coup of March 9th, 1945.

He left for the “Maquis” (the underground) at the end of 1946 and returned to Hanoi in 1952.

His official biographers (communists or infidels) evoke “tuberculosis” as a cause for his return…

In fact, Bui Xuan Phai was fleeing from what many of the intellectuals and artists of the maquis would later denounce: the new ideological order, elaborated by Mao Zedong in Yan’an (China) in 1942 and adopted by the Vietminh. In 1950, the Chinese Luo Gui-Bo, leader of a mission for political advisors, introduced “purges” and “self-criticism” in the areas controlled by the Vietminh.

The Maoist “chen feng” became the Vietminh “chinh huan” (reform-instruction). The artists, furthermore, had to imperatively elaborate (one would not dare write “create”) “character-types”, essentially “heroic” peasants and workers fighting “French colonialism”, its “puppets” and the “feudal class of landowners”.

Beyond a propaganda – understandably – to mentally belong, the true artist is expected to deny himself.

This dogmatism, imported, does not date from the end of the 1940’s.

Michel Aucouturier gives us a rigorous historical summary in “Le Réalisme Socialiste“, identifying the relations between the communist ideology and the art, extremely complex, as many artistic movements came to graft themselves on this one. Let’s just evoke the “Proletkult” and Vladimir Kirilov (1890-1937) who proclaims in 1917:

In the name of our future, we will burn Raphael, we will destroy the museums and we will trample the flowers of art

and to refer to the futurism of Maiakovski (1893-1930) who writes in 1918:

The streets are our brushes,

the squares our palettes

“Red, art and utopia in the land of the Soviets“, edited by Nicolas Liucci-Goutnikov, offers us, in addition, a fascinating illustrated critical understanding of the subject.

The “bourgeois formalism” and the aesthetics of the monopolistic proletariat are dated concepts imported into the maquis of North Vietnam. It took the courage and talent of To Ngoc Van to oppose art and propaganda in an article dated July 1st, 1947, and to (re)affirm that the former has an eternal value, the latter a momentary interest.

In 1949, still Tô Ngoc Van in another article (“Should we or should we not study?”), denies to the masses the faculty to criticize the artists because they do not have the necessary qualification for lack of study(s)… Nguyen Dinh Thi (1924-2003) will say it in a great debate in the Viet Bac – September 25-28, 1949 – and the hard, exclusive, dogmatic line won under the banner of To Huu (1920-2002).

To better understand the mentality imposed by To Huu, who until his death was the “official poet” of communist Vietnam, let’s read an excerpt from one of his poems written in the 1950s:

Long live Ho Chi Minh

The beacon of the proletariat

Long live Stalin,

The great eternal tree

Sheltering peace under his shadow!

Kill, kill again that the hand does not stop for a minute

So that rice fields and lands produce rice in abundance,

For taxes to be collected quickly

For the Party to last, let us march together with one heart

Let us worship Chairman Mao,

Let’s worship Stalin forever

This mentality, this activism, are not to the taste of Bui Xuan Phai. But the painter, like many, eludes more than he fights. To oppose is a very different posture. That Tran Dan (1926-1997) will endorse.

Who was Tran Dan and why link him to our painting?

From the time he joined the Party in 1949 until Dien Bien Phu, Tran Dan remained within the norm of the maquis. The energy required for the war effort smoothed out the opinions. But, once victory was achieved, Tran Dan, from 1955, inspired by the Chinese contestant Hu Feng (1902-1985) who worked in China, “demanded total freedom of artistic creation, the abolition of the system of political control in the literary activity groups of the army. He asks to be demobilized and to leave the Party” (Ngô Van, p 96).

Earlier he had condensed his program into a few words:

I would like to be a comet that with a terrible shock on the earth reddens the immense sky of life and art.

One can understand the difference in sensitivity with To Huu’s “project”…

The answer? He was sentenced to 3 months (June 13th-September 14th, 1955) of prison – and permanent self-criticism – and then forced to wander, as he was excluded from everything, with his Catholic companion (therefore suspect).

Yet he is not alone.

The imported Chinese Maoist orthodoxy was soon challenged by a whole current of thought, first from the army and then relayed by a growing number of intellectuals. In the spring of 1956, Tran Dan participated in the collective work “Gia Pham 1956” (Les Belles Œuvres 1956) with his poem “Nous vaincrons“. The work is seized, Tran Dan “vilified by the Union (sic) of the writers of Hanoi” and condemned again to 3 months of prison.

He tried to cut his own throat.

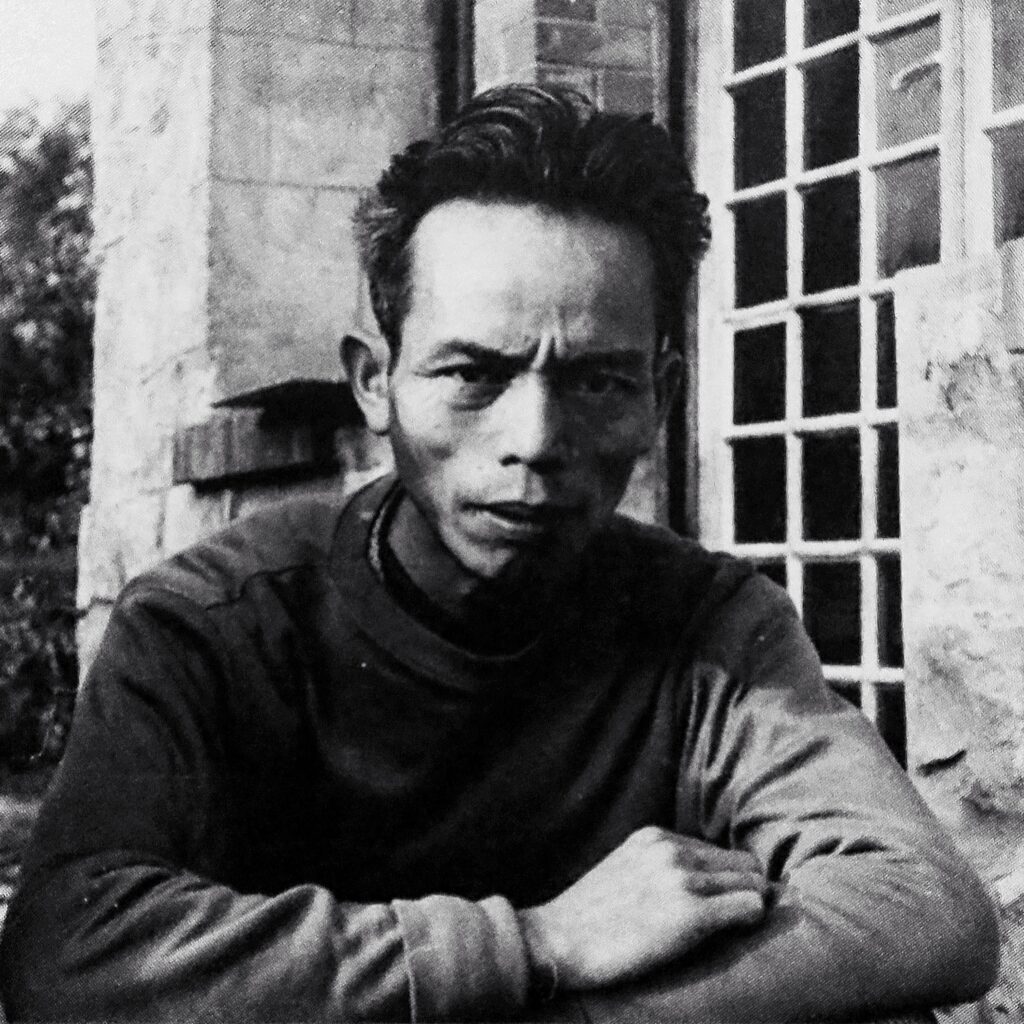

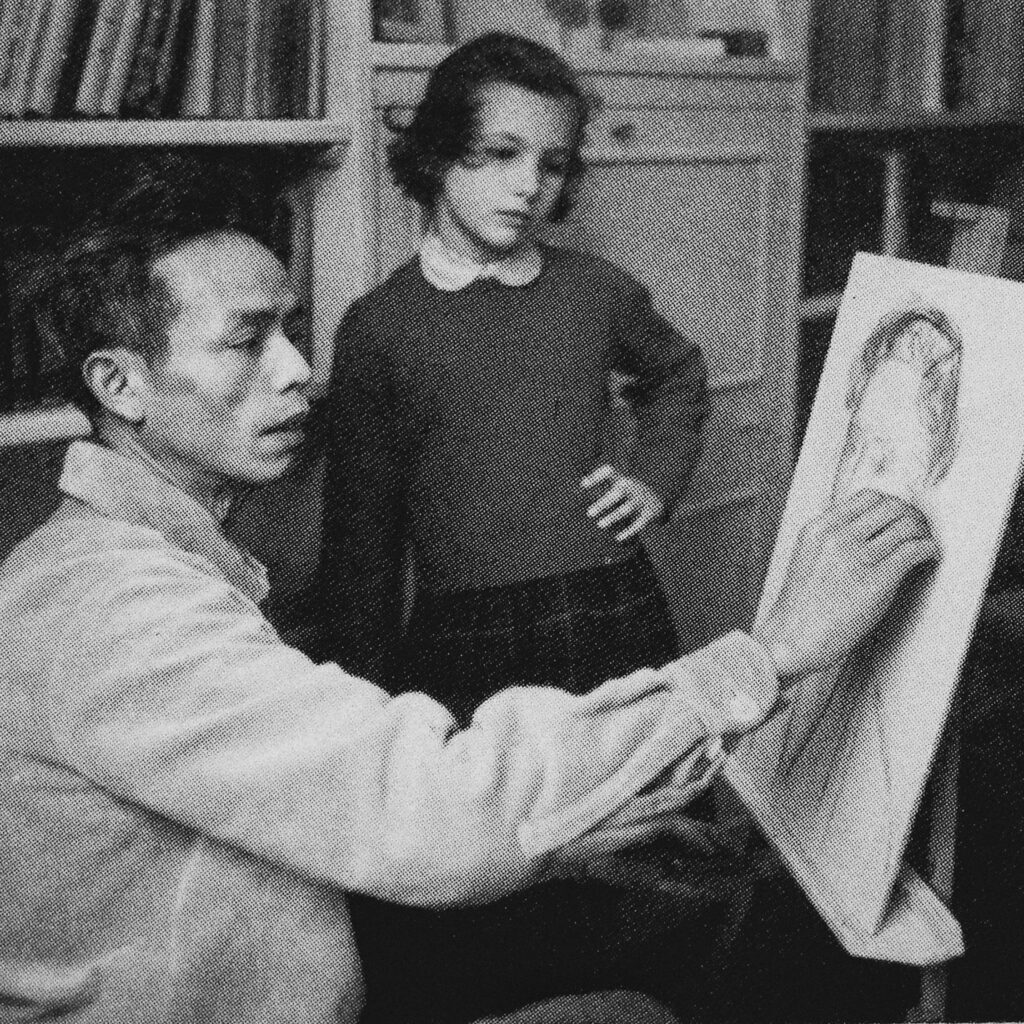

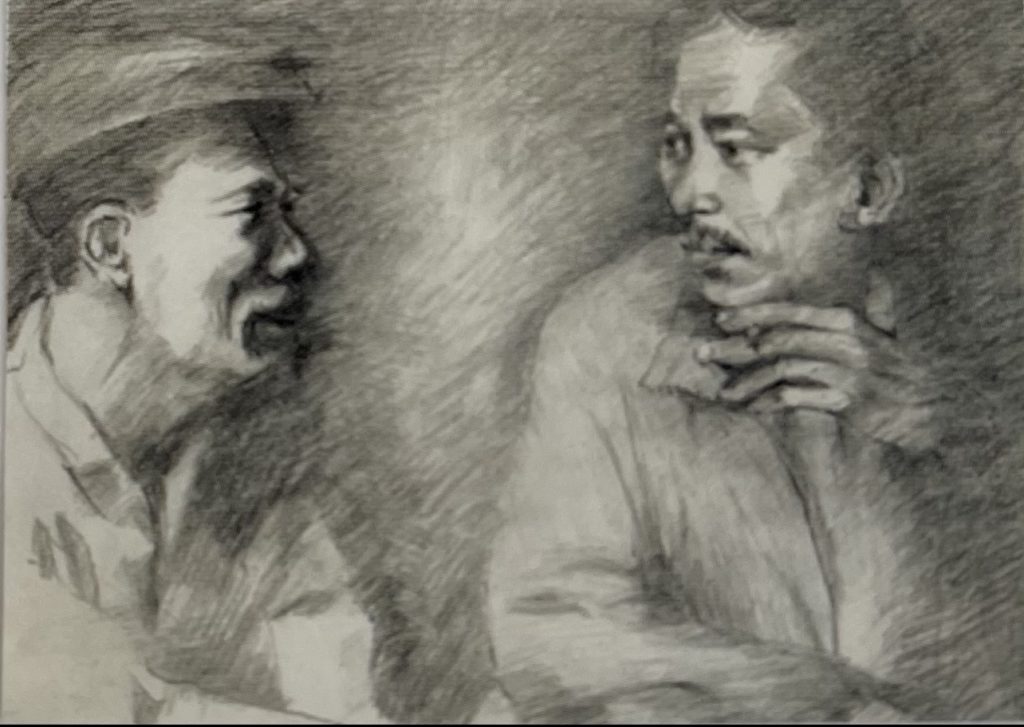

Drawing by Bui Xuan Phai with Tran Quy Thinh.

On September 20, the first issue of “Nhân van” (Humanism) appeared (5 issues followed until November 20, 1956). Nguyen Sang included a powerful portrait of Tran Dan showing the scar on his neck, the visible mark of his attempted suicide in prison. Others, notably jurists, demanded freedom of the press, of assembly, of travel…

The agrarian reform and the “hô khâu” system (homes and mouths) were denounced.

The repression was rapid, effective and complete: publications were seized and banned.

All the actors in the protest will be qualified as “traitors”, “saboteurs”, “reactionaries”, thrown in jail, re-educated, deported, socially annihilated as well as their families. Ngo Vân (pp101-103) gives us a tragic account.

In 1955, the Hanoi School of Fine Arts reopened and Bui Xuan Phai was appointed professor. But close to the protest movement, he was dismissed from the School in October 1956 after being forced to make his “self-criticism” and saw his works banned from publication.

The system excluded him too. Poverty and wandering follow.

He broke the confinement by painting or drawing tirelessly on all types of supports he could find in his extreme scarcity of the moment. Hanoi was his theme. From a city that is decomposing he made an ode. These were his “Pho-Phai” (the streets of Phai) which will make him famous later. The gray of the walls, the roofs, the asphalt, but also the smelly filth that sticks to the city. Since the beginning of the “Rolling Thunder” operation in March 1965, the bombings of the American aviation overwhelm North Vietnam. On June 29th, 1966, the gasoline warehouses of Gia-Lâm were destroyed. American pilots who were shot down were paraded around, and the bombings intensified. In August 1967, hundreds of deaths tragically testify to this. It was a battered city, outraged, forced to “so tàn” (evacuation), a source of emotional and social dislocation. Air defense and anti-aircraft shelters “dressed” the city.

In this year 1971, families have been sent to the countryside since 1965 in fear of American bombings. Closed shop fronts and empty streets are the sad norm of a ghost town.

Only a few very rare cafes like the “Thuy-Hu” (By the Water), remain the meeting places for “eccentrics” like Bui Xuan Phai and Nguyen Sang, among others.

The work, certainly the most powerful portrait ever executed by the artist, was painted (personal communication in 1994 from Tham Thi Don Thu) at Bui Xuan Phai’s own home (since 1964), 87 Thuoc Bac Street (“Northern Remedy” ie “Medicine”) in Hanoi where Thinh posed.

Tran Quy Thinh: Emaciated (who wasn’t in Hanoi in 1971?), stooped, neck bent forward, hands, strong, clasped, the left resting on the right clutching a book itself. An extinguished cigarette, frozen between two fingers. The distant, disillusioned gaze of this man with his baggy clothes still conveys that dry, restrained strength that the Hanoian still retains today. Let’s compare Thinh’s expression on the canvas with that of the drawing (unfortunately we don’t have the date) where Bui Xuan Phai represented the two men conversing…

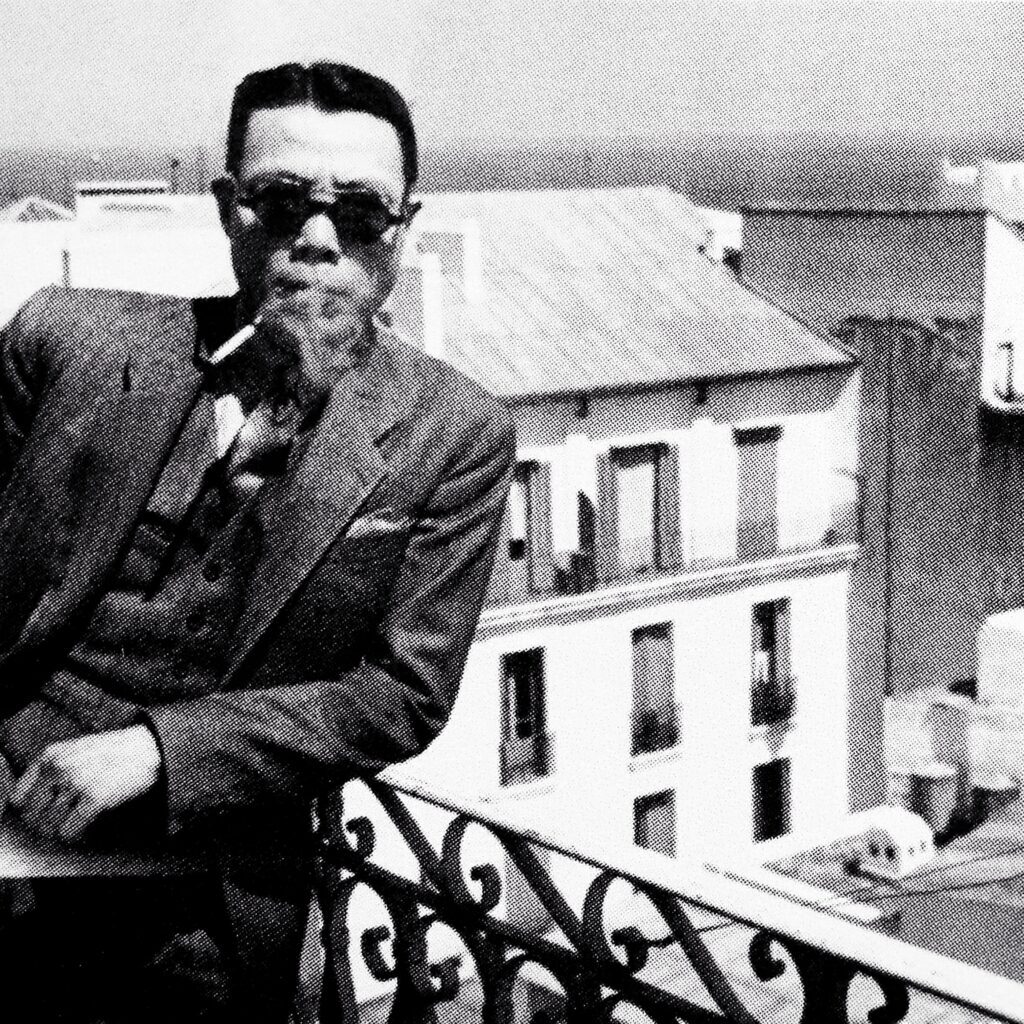

Portrait of Tran Dan.

Pen-and-ink drawing by Nguyen Sang (Nhan Van N°1, September 20th, 1956)

Bui Xuan Phai treats his subject here by combining shades of green and brown with large brushstrokes. The brown of the hair, the shirt and its buttons, the book and the pants form a central, vertical line. The uniform background, green, and neutral, tries to draw the model dressed in a jacket of the same tone. The large size (78.5 X 56 cm) of the oil on canvas is exceptional in the work of the painter, as was the material, as scarcity still reigned in Hanoi at the time.

A deserted city, a weary painter, a majestic painting. But who is the model?

Born in Hanoi in 1932, Tran Quy Trinh (who died in 1986) entered the prestigious French film school Louis Lumière in Paris in 1957. There he discovered the “Left Bank” where he lived and experienced the joys and continuous questioning of the “City of Light”. Back in Vietnam, he became a cameraman and then a director of scientific documentaries and documentary films (“Impressions of Spring”; “Women in Vietnamese Painting”; “The Life of Rice”; Isayo Takano – the Japanese reporter of “Akahata” (Red Flag) ; Professor Tôn That Tung (1912-1982), a specialist in liver and pancreas surgery. His last film denouncing the evils of Agent Orange won a prize in Leipzig.

Thinh was a member of the wealthy class that did not leave for the South after the Geneva Accords of 1954, like his father-in-law, the mayor of Hanoi Tham Hoang Tin. All of them were strong supporters of the new regime just settled in. They eventually understood, much later, that their bourgeois origin is an insurmountable flaw in the communist ideology. Their social elimination followed a more or less rapid but ideologically programmed marginalization. Later, the local authorities strongly advised them to leave for France… It is a generation stuck in its naive certainties, haggard of the lost time but complicit by its passivity tinged with cowardice of a Communist Party which only applies its program.

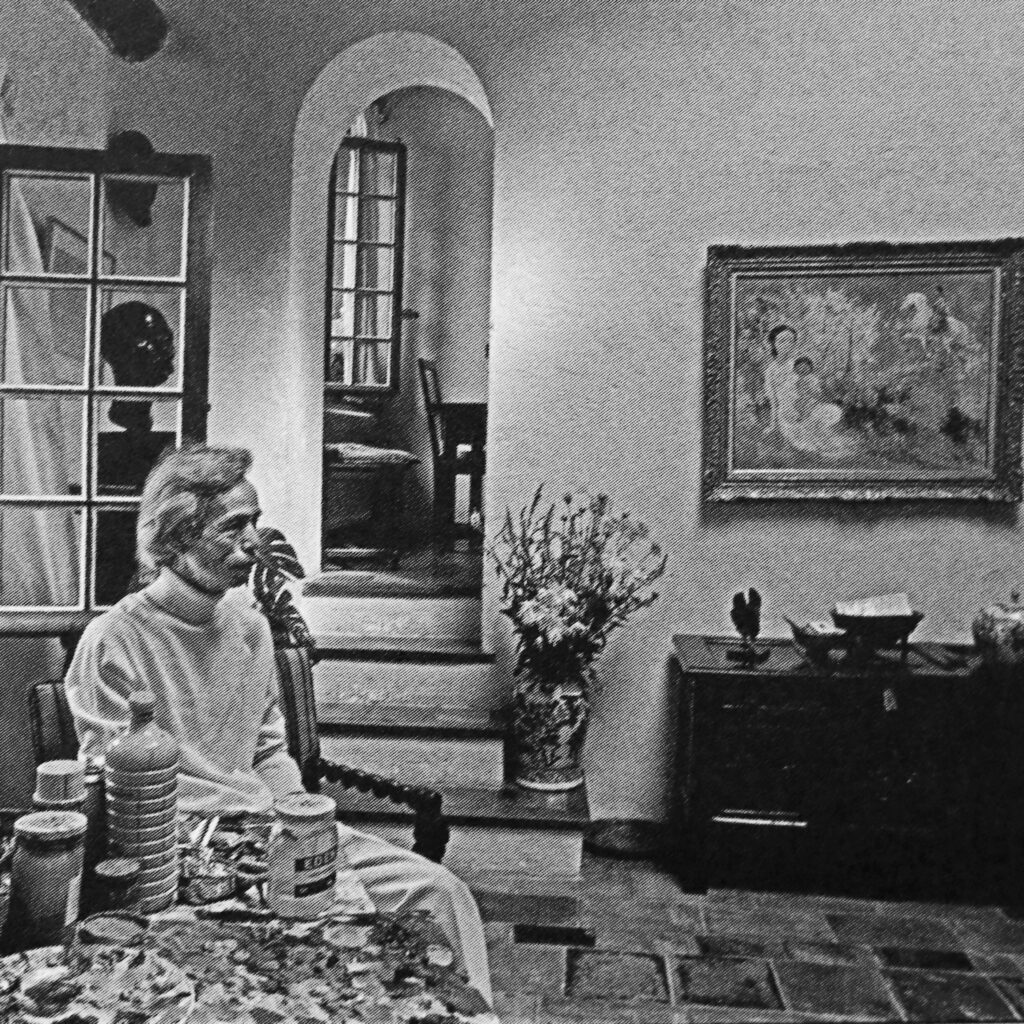

This ambiguous state of mind, to say the least, I got to understand it better thanks to the numerous and incessant conversations I had since the 1990s with direct actors of what must be called a drama: Tham Thi Don Thu – Thinh’s wife – and Tham Vo Hoang his brother. Their relatives (such as their brother-in-law, Professor Le Thanh Khoi), who had lived in France for a long time, provided me with many details. I completed the story in the early 2000’s with Xuan Phuong, a valuable witness.

Others spoke to me anonymously. At 4 rue du Docteur Gosselin in Cachan, at Tham Thi Don Thu’s house, at 30 rue Henri Barbusse in Villejuif, then at 20 avenue d’Ivry in Paris, at Tham Vo Hoang’s house, I also saw the material discomfort and the mental misery. As much as the first was of little importance to them, the second was fed by a certain guilt, especially towards their own children, who were labelled as being of bourgeois origin and therefore discriminated against. Easily accessible accounts provide good information on the period: that of Xuang Phuong (“Ao Dai du couvent des oiseaux à la jungle du Vietminh” Paris 2001). That of the more than sulfurous Georges Boudarel (“Cent fleurs écloses dans la nuit du Vietnam, communisme et dissidence 1954-1956“. Paris 1991). Philippe Papin, on the other hand, specifies interesting elements in his “Histoire de Hanoi“, Paris 2001. Very incisive and courageous, Ngô Van, “Le joueur de flûte et l’Oncle Hô“, Paris, 2005 delivers a concise and striking account because of commitment.

Bui Xuan Phai loved this portrait and asked Tham Thi Don Thu, the widow of the model, to lend it to him for his exhibition in Hanoi in 1988. The painter saw it once again at the opening but his lung cancer prevented him from returning.

Bui Xuan Phai, Tran Quy Thinh, Tran Dan, To Huu. Four destinies but not four epics.

- To Huu died in 2002.

- In 2007, the State Prize for Art and Literature will be awarded to Tran Dan, a pathetic attempt at rehabilitation… 10 years after his death…

- Bui Xuan Phai and his model offer us this portrait which is the tragic mirror of the object that paints its subject. It testifies to the negation of the human in the communist system that ends in a tragic buffoonery.

But, and this is comforting, in this ode to two lives, there is Tran Dan’s mischievous smile that delights us while To Huu’s irremediable oblivion reassures us.

Jean-François Hubert